Special report: Inside the Hinduja family feud

At the heart of the Hinduja family feud is a letter signed by the brothers to stay undivided. But there's a lot more than meets the eye

The Hinduja brothers: (Standing, from left) Gopichand, Prakash and Ashok; (seated) Srichand

The Hinduja brothers: (Standing, from left) Gopichand, Prakash and Ashok; (seated) SrichandImage: Umesh Goswami

It’s quite unlikely that the Hindujas have not heard of the old American proverb, ‘Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations’.

If not the exact words, they would certainly have come across some variant of it, found across cultures, describing the inability of the third generation to manage the wealth passed down to them by their grandparents and parents. Certainly, as with many family businesses before them that have thrived before splitting, the Hindujas, modern-day torchbearers of India’s family business legacy, thought it wouldn’t befall them.

For over five decades, Srichand Hinduja, and his three younger brothers, Gopichand, Prakash and Ashok, had built up an empire—almost equivalent to the GDP of Mongolia—cutting their teeth across continents, hobnobbing with politicians, film stars, and royalty. All through that time, the brothers painted a unified front, often comparing themselves to the righteous brothers of the Ramayana, with different bodies and one soul. They share a mansion with four inter-connected houses spread over 67,000 sq ft in London’s upmarket neighbourhood of Westminster and are neighbours to the British Queen.

Today, however, the fab four, as they have been known for long, are a divided house and three of the brothers are busy firefighting to douse a dispute involving the heirs of the patriarch. As Srichand fights dementia, something insiders say has been ongoing for three to four years, his daughters, Vinoo and Shanu, have stepped forward to challenge an accord reportedly signed by the brothers on the ways to split the family empire.

“There is some serious mediation going on at the moment between Gopichand, Prakash and Ashok with Vinoo,” says a person who has worked closely with the group. “They would prefer that the issue is sorted out amicably and not be discussed in public. Srichand’s daughter must feel that her uncles aren’t being fair to her. It’s also possible that there are properties in his name and they are using this opportunity to take over those.”

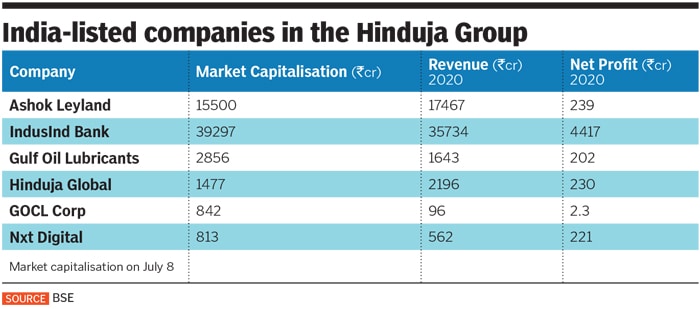

For the close-knit Hinduja family group, whose businesses span some 48 countries, the ongoing feud will have serious repercussions, including a split in fortunes. Their empire is worth $13 billion (as on July 10), spread across automobiles, telecommunications, health care, defence, and financial services among others, and employs some 150,000 people. The group controls companies such as Ashok Leyland, Gulf Oil, IndusInd Bank, and Hinduja Healthcare.

At the heart of the dispute is a 2014 agreement signed by the four brothers, which said that the assets held by one brother belong to all and that each will appoint the others as their executors. “It is very unfortunate that these proceedings are taking place, as they go against our founder’s and family’s values and principles that have stood for many decades, especially ‘everything belongs to everyone and nothing belongs to anyone’. We intend to defend the claim to uphold these dearly held family values,” Gopichand, Prakash and Ashok said in a statement in late June. The SP Hinduja Banque Privée has not responded to a questionnaire from Forbes India till the time of writing.

That means a long-standing legal tussle, unless the rather reticent group decides to sort out the mess sitting across their dining table. An all-out war could involve mudslinging and digging up of business deals that have always been shrouded in secrecy.

“What you are seeing about the group in public is only half of what they have,” claims an executive who has worked for the group. “A bulk of their business is in trading, and their assets far exceed what is known in the public. From Iran to Sudan, trading has always been their primary interest. So, the best option would be mediation and amicably solving the differences. They were the last standing bastions of the family business.”

At the root of the ongoing trouble in the Hinduja family is the unwritten guiding principle for many family-run businesses in India. That everything belongs to everyone.

“That’s the basic principle across family businesses in India,” says Kavil Ramachandran, executive director at the Thomas Schmidheiny Centre for Family Enterprise at the Indian School of Business (ISB). “There are also no governance policies or clear ownership rights in place, as they don’t think beyond one generation. Ideally, the Hindujas should have constituted shareholder agreements and policies that were legally vetted. They have clearly failed in putting that together.” In India, family businesses like the GMR Group, the Burmans of Dabur, and Murugappa Group have formal family constitutions.

For over five decades, since their father Parmanand passed away, the Hinduja brothers had rallied behind Srichand, the group chairman. Between them, they had demarcated their businesses, and passed that along to their next generation. While Srichand looked after operations in London, Gopichand was co-chairman and the man many reckon to be the mastermind behind the group’s phenomenal growth. Prakash looks after the Europe business based out of Monaco, while Ashok looks after the India business.

Parmanand was a trader who moved from Shikarpur in the Sindh province of Pakistan (then undivided India) to Mumbai in 1914 to become a moneylender, before venturing into importing and exporting dried fruit and tea to Iran. Soon, he diversified into jute and distributing Indian films, dubbed into Farsi. The brothers joined the business one by one from 1952 onwards after completing their education. They also had an elder brother, Girdhar, who passed away in 1962.

Over the next few decades, Iran became the group’s base, even as allegations grew that the Hindujas were dealing in arms for the Iranian government, though they were never proven. What’s known, however, is that during their time in Iran, they owned land and were deeply trusted by the administration, which had even tasked the group with procuring potatoes and onions from India, transiting them through Pakistan, as the oil-rich nation went through a food shortage.

In 1971, Parmanand passed away, reportedly leaving behind some $1 million, and Srichand took over the reins. By 1979, the group had moved base from Iran, following the Iranian revolution, to London, where it continues to be headquartered. Around the same time, the group established a finance company in Switzerland called the SP Hinduja Banque Privée.

While the group continued to focus on trade, it also planned to diversify and conquer new frontiers. This meant mopping up assets across sectors, and through the 1980s the group went on to acquire Ashok Leyland, the truck manufacturer headquartered in Chennai, and Gulf Oil’s business outside of the US from Chevron.

“They have always been a conservative group,” says the executive who had worked at Hinduja. “That’s quite evident in the choices they have made. They have avoided a lot of business because they look for stable returns. If you look at many groups and their investment decisions, they have 40 percent success and 60 percent chance of failure. With the Hindujas, it is 70 percent success and 30 percent failure. But these forays were also to take the light away from many of their undisclosed businesses, and give credibility to the group.”

Over the next few years, the Hinduja empire would go on to expand into areas, mostly within India, such as banking, with the launch of IndusInd bank, health care, information technology and defence. But there were also deals that didn’t work out. In 2007, the group made a $20-billion bid for 100 percent of Hutchinson Essar, before Vodafone eventually bagged it.

Along the way, the brothers also courted controversies, including alleged kickbacks from the sale of Bofors weapons, which they have denied and were later acquitted for. It was alleged that the Hindujas were paid a commission to swing the deal in the Swedish company’s favour. They were acquitted by the Delhi High court in 2005 although allegations of arms deals have followed the group for decades, within India and outside. “Ashok Leyland is among the largest suppliers to the military and had a rich British heritage. That was the thinking behind the Ashok Leyland purchase,” the former executive says.

Everything for everyone

Amid all the success, the group had always echoed the sentiment of collective ownership. In fact, they were so close that three of the brothers’ sons had their weddings on the same day in Mumbai, with many guests being flown in from London and Geneva on private aircraft. The brothers have also been rather similar in their sartorial styles, down to their spectacles. They are devout Hindus, abstaining from meat and alcohol. They have counted among their friends global leaders including Tony Blair, George H Bush and Margaret Thatcher.

“All the houses belong to everybody; all the cars belong to everybody. There is no ‘this is mine and this is yours’. All the children belong to everyone. We have kept one kitty. Everyone works as a duty. There are no wills,” Srichand had said in an interview to Financial Times in 1994.

This is corroborated by the former executive who worked with the Hindujas for over two decades. “As far as I know, between the brothers, there were no problems,” he says. “They have always stood by the belief that everything belongs to everyone. In fact, Srichand Hinduja had been advocating that for very long and the pact was his brainchild. So, knowing Srichand the man, it is unlikely that he would go back on this philosophy.”

In that context, what is happening in London is just the tip of the iceberg. The trouble in the family seems to have begun sometime in 2015, when Srichand told his brothers that the letter signed by them in July 2014 appointing each other as their executors be cancelled.

In 2018, the three brothers reportedly tried to wrest control over SP Hinduja Banque Privée, which is in Srichand’s name, on the grounds that he lacked capacity. SP Hinduja Banque Privée is a private bank focussed on wealth management and private banking, trade finance, corporate advisory services and global investment solutions. In November 2019, Srichand approached the Business and Property Court in London seeking a declaration that the 2014 letter was revocable. The three brothers contested that Vinoo, Srichand’s daughter, shouldn’t be representing her father in the proceedings. The court, however, confirmed Vinoo’s appointment.

“What happened in the bank case is that existing rules required a single promotor, since accountability cannot be passed on to others. Naturally, as the patriarch, Srichand became the promoter,” the former executive says. “The understanding was that the bank did not belong to him alone. Srichand has also been incommunicado since 2017.”

The SP Hinduja Banque Privée currently has a presence in Dubai, London, Paris, New York, Chennai, Mumbai, Mauritius and Cayman Islands, and reportedly manages assets of about $365 million according to TheBanks.eu, a directory of banks in Europe. In 2011, the bank had assets of over $1 billion, which have since been declining.

Over the past few years, there has also been a move to rewrite the bank’s legacy, with very little reference to the other brothers’ contributions. “Srichand has broken barriers to bring cultures together in truly unique ways by advising world leaders, bringing Indian culture to the world through cinema, and creating unprecedented gateways between the US, the UK and India,” the bank says about its founder, Srichand Hinduja. “It is this legacy that is supported by his wife Madhu, and is upheld by his daughters, Shanu and Vinoo, and his grandchildren Karam and Lavanya, who work to uphold his principles and extend his purpose to new frontiers.”

In May 2020, the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority revoked the banking licence of the bank for reasons including contravening anti-money laundering regulations and failing to seek their approval for the issue, transfer or disposal of shares relating to the alleged sale of the bank, and for repeatedly failing to maintain a net worth of not less than $400,000. The authority also pulled up the Cayman Islands subsidiary for not submitting audited accounts for 2018 and 2019 while noting that the CEO Gilbert Pfaeffli was no longer a “fit and proper” individual to continue.

Around the same time, the bank appointed Shanu’s son Karam as CEO. Shanu is chairperson of the bank, and has been vocal about the toxic culture for women in the banking sector, and has repeatedly questioned the bias against them.

But the issue is deeper than just the fight for control of the bank, the former executive adds. “The bank is not even 10 percent of the wealth of the Hindujas and is probably worth $2 billion or $3 billion. What happens to the rest of the wealth, assuming it is likely to be a four-way split? The whole issue over the bank is only an excuse and the problems are far deeper.”

So, what’s at stake?

The group’s publicly listed companies in India have a combined market capitalisation of over ₹67,000 crore. That’s barely much by any standards. But there are also numerous ventures that aren’t listed. At the helm of all those businesses are mostly the third generation of the Hinduja family, including Vinoo who is contesting the agreement between her father and his brothers.

“All the next generation children were given choices on what they wanted to do,” says one of the former executives. “Regardless of their gender, they were free to pick what suited them.” While Srichand’s daughter Shanu is chairperson of SP Hinduja Banque Privée, with her son as the CEO, Vinoo looks after the health care business. Srichand’s son Dharam passed away in 1992, reportedly by suicide, after his parents objected to him marrying a Roman Catholic woman.

“Gopichand is actually the brain, the philosopher, and the mastermind behind many things,” says the former executive. “His children, Dheeraj and Sanjay, have also come into their own, and are among the brightest minds in the group. That certainly means there is a lot of friction among the third generation, and a fear that the others could lose out.” Sanjay is chairman of Gulf Oil, while Dheeraj is chairman at Ashok Leyland, two flagship companies of the group. “They are seen as a natural threat.”

Prakash’s son Ajay looks after GOCL, which has interests in real estate, land development, infrastructure contracts and commercial explosives, among others. His brother Ramkrishan, often called Remi, used to look after Hinduja Global Solutions. Ashok’s son Shome is expanding the group’s foray into renewable energy and is on the board of Gulf Oil.

“The next generation is protected by a layer of the four brothers,” says the former executive. “If they fail in a venture or can’t find much success in a particular direction, they are brought back into the fold, and are then handheld till they find success.”

The Hindujas have also always given importance to professional management and given them a free rein, particularly CEOs. “They don’t like letting go of people,” the former executive says. “When you join the group, they may not pay industry standards. But they offer you a safe job, and even if you are incompetent, they don’t let go except under exceptional cases. And with the top management, they always give a free hand.”

This was visible at Ashok Leyland, where the company gave a free hand to R Seshasayee in running the company. During his time at the automaker, Ashok Leyland’s turnover increased five times from ₹2,045 crore to ₹12,093 crore, net profit rose 30 times and market capitalisation grew 14 times.

“Ashok Leyland has always had a very important and strategic role in the country,” says Vinay Piparsania, consulting director–automotive, at Counterpoint Technology Market Research. “As a public transport provider that also has crucial roles in defence and exports, it is very important that the company continues to be seen as professional in every aspect. The group has always ensured that the professional management has a free hand.”

For now, the brothers maintain that the feud has no impact on business at the group companies. “We would stress that this litigation will not have any impact on our global businesses, which will continue to function as they have been,” they said in their June statement.

So, what happens now?

“The best option right now is to sit and discuss the issue and come to a solution. If there is need, then use professional mediators,” says Ramachandran of ISB. “The cost of litigation is massive and there is often no end to such cases.”

Already the UK court, where Srichand had challenged the July 2014 letter, had ruled that there was evidence that Srichand himself sought to disavow the letter. It also suggested that Prakash too had earlier sided with Srichand before choosing to jump sides.

“It was Srichand, not Vinoo, who originally instructed Clifford Chance [law firm] in 2015. Mr Kosky’s evidence explains that Srichand organised for him and one of his partners to meet the brothers on May 2, 2015, that at that stage it was thought that Gopichand, Ashok and Prakash would agree to whatever Srichand proposed, but that shortly after the meeting Gopichand and Ashok referred to the July letter and sought to rely on it,” the court order says. As a result, Clifford Chance sent an email on May 25, saying Srichand and even Prakash did not consider themselves legally or morally bound by the letter.

“There have been murmurs [of unsatisfaction and disagreements] between the brothers for long,” says the executive quoted earlier. “But they have always found a way and reached an understanding.” But the discord between the third generation is coming into the open. Last September, the third-generation members on the board of Hinduja Global Solutions resigned, following differences between them. Ramkrishan was the chairman, Shanu the co-chairperson, and Vinoo was a director.

“Vinoo and Shanu have taken the call to go public,” the executive says. “That means it’s not murmurs anymore. Egos across the next generation are hurt, and in the longer term, it is irreparable.”

With mediation underway, it’s probably time for the Hindujas to go back to the drawing board to hold the family together. They have managed to sail through rough waters in the past. It’s time for them to do that once again.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)