The government's empty pockets

The pandemic has punched a hole in government finances limiting its ability to spend that could lead to a period of low growth

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer PawarIn early June, as India tentatively got back to work, businesses cheered. At 10,000 Covid cases a day, the count seemed manageable. If Indians could learn to live with the virus, it was hoped that the hard stop to economic activity in April and May would soon be behind us.

During the two-month lockdown, government revenues had evaporated with GST collections falling to ₹32,172 crore in April and ₹62,151 crore in May, lower than the ₹100,000 crore monthly run rate. State coffers had run dry primarily around the ban on alcohol sales.

Simply put, a government that does not earn cannot pay its bills. With the lockdown lifted on June 1, markets rallied. Two-wheeler companies spoke about demand coming back to pre-Covid levels. Retailers stocking everyday items saw sales resume.

Global ratings agencies were more circumspect. At exactly the same time as India reopened, they either lowered ratings or revised the outlook to negative. April had seen growth projections for FY21 at 1 to 2 percent, but these had been steadily revised downwards. The decline in growth has a direct impact on government revenues.

Although India has never defaulted on its sovereign debt, those that assign sovereign ratings—Fitch, S&P and Moody’s—were concerned about the loss in output punching a hole in government finances. “We’re watching this closely, with a particular emphasis on the potential for structural damage to the economy should conditions deteriorate beyond our expectations,” Andrew Wood, analyst at S&P Global Ratings tells Forbes India.

Now, as the four month-long pandemic shows no signs of slowing and the rising case load (now averaging 40,000 daily cases) resulting in city and district-wise lockdowns, growth projections have been lowered even further. Both Fitch and S&P have pencilled in a 5 percent reduction in output in FY21. Indian rating agency ICRA recently downgraded their growth projection to 10 percent and Pronab Sen, former chief statistician, has spoken about a 12.5 percent decline.

Three points bear mention. First, a large part of India’s growth has been powered by consumer spending since 2013. As banks and NBFCs cut back on consumption loans, it remains to be seen whether government spending, investments and exports can drive growth. So far there is no evidence to suggest that these three can pick up the slack.

Second, going into this pandemic, government finances were in poor shape. India’s central government deficit was budgeted at 3.8 percent for FY21. Add states and government of India-guaranteed bonds for undertakings like the Food Corporation of India or Air India and the number stood at 8 percent. Third, unlike the 2008-09 Lehman crisis, there is now a synergistic relationship between central and state finances. They have to work with each other. “While we may come out of this with the central government numbers smelling like roses, it is the state government numbers that could retard growth for a long time,” said Sen.

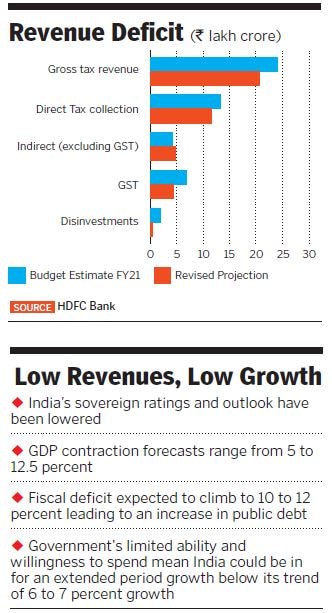

A poor growth outlook and already high deficit numbers paint a dismal picture for FY21. The duration and severity of the pandemic is still unknown. In estimating what government finances could look like, economists have evolved a framework that looks at the decline in growth, the tax elasticity and what specific taxes could bring in and what the deficit numbers would look like. At the same time, defence, health, the rural employment guarantee programme and a bank recapitalisation programme would almost certainly need more money than has been budgeted for. Major areas of decline would include money from disinvestment and telecom spectrum auctions. Increased revenue from higher excise on petroleum products is likely in FY21.

How steep could the decline in taxes be? Abheek Barua, chief economist of HDFC Bank, predicts that tax buoyancy will fall from 1.2 to 0.7 even as he has predicted only a 5 percent fall in growth. Gross tax revenue, according to HDFC, would decline to ₹2,000,6000 crore compared to a budget estimate of ₹2,400,2000 crore—a decline of ₹360,000 crore. For Sen, that number is at ₹450,000 crore. He puts the deficit number for states at ₹300,000 crore. Most of this is likely to come from GST with income tax, corporation tax and customs duties accounting for lesser falls.

All economists and ratings agencies that Forbes India spoke to pointed to a fiscal deficit number of 10 to 12 percent for FY21, with the central government deficit at ₹650,000 crore, states at ₹400,000 crore and ₹120,000 crore for government-guaranteed borrowings by companies. The new borrowing programme by the Centre gives it leeway to borrow ₹400,000 crore more in FY21 while states can borrow up to 2 percent more of their state gross domestic product.

In effect, this means that while the central government would have some extra cash to spend, the states will almost certainly have a spending deficit even after the extra borrowing. “Virtually every ministry is cutting back on expenditure. It is across the board and we still don’t know the specific numbers as yet, but the axe could come on capital expenditure on roads and railways,” says Barua. Dearness allowance increases for government employees have been suspended till July 2021.

What could the limited spending capacity mean for growth? This is something economists are watching closely. “It remains to be seen what impact the crisis will have on India’s medium-term economic growth and whether a growth rate of 6 to 7 percent, as previously estimated, will be achievable, especially if financial sector weaknesses persist,” says Thomas Rookmaaker, director, sovereign ratings, at Fitch Ratings.

So far, at 1.9 percent of GDP, the Aatma Nirbhar package has been restrained in its spending. With state and central governments limiting spending, the potential for inflation flaring up is also limited. In a July 22 FICCI conference, chief economic advisor Krishnamurthy Subramanian spoke about a stimulus announcement once the virus is under control. While it remains to be seen if that will be enough to take care of lower demand on account of wage loss, a lesser decline in growth would do the trick for this fiscal.