How To Manage Risk in a Global Supply Chain

Managing risk in a global supply chain in many cases requires accounting for and bridging the differences in culture, language, values and organizational behaviour

A supply chain may not be quite as dynamic or complex as capital markets, but when it comes to managing supply chain risk the challenge is, arguably, can be as formidable as managing risk for instruments such as mortgage-backed securities or credit default swaps. Perhaps that is because of all the moving parts that there are in a supply chain, which we define as a network of companies that cooperate to convert ideas into goods or services for their customers.

In an ideal world, the interests of these companies are aligned. They adapt to structural shifts in the market, such as currency fluctuations or other economic shifts, and are agile enough to respond quickly to changing supply and demand. But without this ‘Triple-A’ approach[i], risks can become significant and multiply, especially in a global environment. In this article, we highlight those risks and suggest what companies operating in a global environment can do to manage them. (Note: The facts and circumstances of the scenario we below are true; however, the names of the company and key personnel are not).

The following scenario is an example of what can go wrong in a global supply chain if sufficient attention is not paid to managing risk.

Kai Chen was walking back to his office to prepare for his daily conference call with his French executives in Paris and customer representatives in the United States. The weight of the program he was responsible for was definitely having an impact on him, but he maintained his erect posture and calm expression. However, the call would prove to be unsatisfactory and people would be upset, though Kai had difficulty understanding why. After all, his people had made great strides since the program was sourced to them one year ago.

Kai was the Operations Manager for Nanjing Automotive, a Tier One auto parts supplier of power train components in Nanjing, China. The company, a Greenfield operation, had been started 2 years earlier by a large global automotive parts company in France, part of that company’s strategy to develop a significant supply position in China, just as the auto parts market was experiencing significant growth. Since that time, Nanjing’s business had grown substantially, both from local contracts with Chinese automotive customers, and customers in North America and Europe. That was the good news. The challenges they faced, however, were numerous, including unclear technical specifications, resource shortages, and unreasonable, demanding customers.

The contract causing the most grief for people at the facility was one for a new control module for an electronic 6-speed transmission, technology that had been proven on high-end, low-volume vehicles, and that was now being introduced in lower-cost, mass market cars. The control module’s performance had exceeded expectations in the market, and demand for Nanjing’s components was far higher than originally anticipated. Kai pushed up his glasses and looked over the daily production numbers once more before dialling the telephone.

Meanwhile, near Paris, Bernard Moreau, Vice President of Procurement and Supply, looked up as two managers entered his office for the daily conference call with their facility in China and their customer in Detroit. It was 11 a.m. in Paris. Timing for the call was OK for Bernard and his team, but the sun was going down in China and just coming up in the United States.

The company’s Korean facility seemed to be doing fine with a similar product for Hyundai. Kai’s project in China, however, had grown out of control very quickly since the operation had started work on it one year ago. Its American customer, normally very demanding, had been struggling financially for several years, and was directing its Tier One suppliers to do whatever it took to drive down costs, including establishing supply sources in emerging markets around the world. Its new operation in Nanjing had seemed like a good candidate for the power train control module project, and though the production ramp up was faster than initially planned, the operation was still having issues with quality.

Bernard had two people on the ground in Nanjing, but they had been in Asia too long, forced to extend their international assignment by 3 years to support the Greenfield[1] project in China, after the successful launch of a new plant in Korea. The two expats were tired and struggling to make a difference. It seemed that the plant had difficulty understanding the expectations and never had enough people to hit the required numbers.

Global sourcing

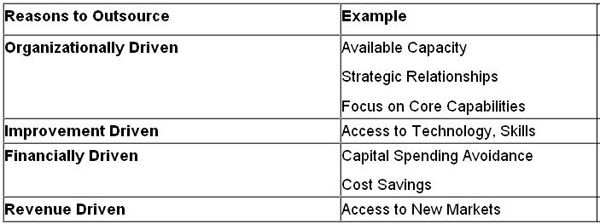

Organizations look global for a number of reasons, as noted in Figure 1. While cost savings may be the first thing that comes to mind, say for a firm considering sourcing product in China, those savings can prove to be more elusive than leadership imagined when they started the exercise. Numerous challenges exist: increasing wages in ‘developing’ markets, logistics costs increasing with the price of oil, frequent travel required between locations in different continents, translation services, licenses, fees, legal costs and the likes. Something else must be driving the offshoring exercise than cost savings alone, as in most cases, the savings are much smaller (or non-existent) through the life of the project than we anticipate. Whether we want to access new technology, new markets, or develop relationships that may lead to sales in that country, firms need to look beyond the labour cost savings.

Figure 1 – Reasons to Outsource

What can go wrong in a global supply chain

One of the largest under-appreciated factors associated with dealing with offshore suppliers is the element of risk. Car companies have become adept at managing suppliers within their traditional supply chains. While there are exceptions, they source capable, healthy suppliers, develop capabilities in those suppliers, and work together to bring quality parts to vehicle assembly in a reliable fashion. When issues arise, the OEM (original equipment manufacturer) has robust (and often invasive, radical) ideas for getting production back on-line.

This is well enough in a domestic environment. The moment we establish a supplier outside our typical environment, however, risk goes up by orders of magnitude and often that risk isn’t understood. One of the key risk factors is a cultural ‘gap’ between the two firms. In this case, that gap between the customer in North America, the supplier’s production facility in China, and the supplier’s executive leadership in France has resulted in a supply crisis characterized by delayed builds, issues of quality, daily global conference calls and third-party resources being called in to “help.” Stress and anxiety are severe, especially for shop-floor middle managers responsible for production in China, managers who can’t appreciate how it got so bad, so quickly. Leadership on all three continents was sensitive to cultural differences but lacked the collective capability to get the necessary performance out of a global, cross-cultural team that was operating from different levels within their respective organizations’ hierarchy.

Culture Gaps

Culture gaps exist between many countries, even those close to each other. Denmark and Belgium, for example, separated by only an hour flight, are culturally very different. Belgium is very risk averse and can be very resistant to change, while Denmark has a higher tolerance for uncertainty and change in their business environments[ii]. One of the key cultural differences between China and North America is appreciation for hierarchy and authority. The Chinese rely on a very clear understanding of ‘rank’ in all aspects of their business, rank that is reinforced not just in structure, but in all meetings and engagements. That hierarchy may not be apparent to Western companies, but it will be reflected in the priority placed on their business. As well, failure to appreciate the hierarchy may result in some innocent-seeming action on a Western company’s part, disturbing the Chinese’s establishment and threatening performance.

In the case of Nanjing, the French moved people in their Chinese around with little regard for existing structure or appreciation for the impact on workers. This including elevating a junior employee to a position at the same level as Kai Chen’s and within his realm of responsibility. A move like that may be common in North America or Western Europe, but moving the lower level employee next to Chen confounded the perceptions of Chen’s authority within his group. As the crisis developed, external resources (consultants and other ‘experts’ from within the French parent company) were brought in under the OEM’s direction to help get the situation under control (again, a tactic that is relatively common in Western culture). The presence of a consultant and daily conference calls upset Chen’s sense of order and balance and compounded his anxiety even further. The pounding on the table by the OEM, the Western parallel planning and a “Just get it done” approach basically shut down the middle management level in the Chinese plant.

Other factors in China made the supply situation especially volatile. At the time, there were 1.5 million open job postings in Jiangsu province, with hundreds of new operations and facilities coming on line in Nanjing, the capital, alone. Turnover and loss of key resources were common, and new positions were often being filled by migrant farm workers in search of higher wages, and with no understanding of a production environment (including standard working hours, practices, safety, hygiene, consistency and standardization, etc. One new employee, obviously unfamiliar with basic hygiene or the use of a toilet, was seen urinating into the floor drain). Transportation of goods was shut down for days at a time between key cities such as Beijing and ocean ports, as the volume of vehicles far exceeded infrastructure capacity[iii]. Layer on this the fact that the product in question was a sophisticated drive control module for a completely reengineered 6-speed electronically controlled transmission, not plastic dolls or pet food. The resulting uncertainty grew to extreme levels without the appropriate risk-management protocols in place.

Levels of Risk and Uncertainty

The first levels of risk are those with which we are familiar. These are known, possible circumstances and often based on previous experience. We deal with these as an organization, with plans that often involve contingency time, money, resources and the likes. Often, back-up suppliers are identified in the case of mission-critical parts.

Next-level risks are typically less likely to be factors, but their consequences are more severe when they become a factor. In these cases, we often don’t know what we don’t know, so best practice is to have a set of standard practices in place to ensure a prompt, effective reaction to a supply situation when it arises[iv]. At an organizational level, this is our version of planning and training for the disruptive events that seem more and more common today.

In this case, the French Tier One and the North American automaker both neglected the risk involved in their project when sourcing it to Nanjing Automotive. The risks were that:

• We have a high-tech new transmission for a high-volume vehicle that we expect to play a role in turning around a struggling automaker. The transmission has only been manufactured in low-volume, highly controlled environments by long term suppliers experienced in new technology launches.

• The relatively young Nanjing plant was launching a brand new technology without the experience of having been through any high-tech launches. This was new to everyone in the plant.

• Their customer was 10,000 miles away, and executive management was in France. So, the need to be agile, especially when solving problems, could not be developed because of distance and different languages and time zones.

• On-site resources and expertise were exhausted and not communicating well due to language and cultural differences.

Categories of risk

Pursuing lower-cost components in such a scenario would be ideal, but that required significant risk management and preparation that wasn’t evident in Nanjing. If we don’t use a local[2], proven supplier in a project like this, then we need to deal with each risk category noted in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Global Supply Risk Categories

Leadership most often considers intellectual property risk, but neglects one or more of the other potential pitfalls. In the case of Nanjing, risks in each of the other categories shown in the diagram proved to be crippling when stacked on top of one another. When the distance is great, transportation costs become significant if production is behind schedule. Here, Nanjing was often flying parts to North America to meet production deadlines, where they were assembled on to vehicles[3]. Travel for executives, technical resources and quality engineers was cumbersome and expensive. Language barriers inhibited effective communication, especially recognition of urgency, and the multiple time zones obstructed efficient trouble-shooting and follow up from remote locations. Production issues in Nanjing and greater customer demand resulted in extreme pressures on Kai Chen and his people, pressure that reduced his effectiveness and created a situation where his commitment to the project’s success diminished. And finally, there was the issue culture – How was our supplier motivated? Did they share our long-term vision? Did we understand the challenges they face and did they need (or want) our support in developing internal capabilities?

There are other possible difficulties in this model, such as legal risk, political risk, etc, but our primary challenges are as noted above. The correct way – the only way – to deal with the level of uncertainty and risk in the production environment of a project like this is with significant resources and investment, needed to eliminate the direct risk from the developing supplier. The importance and urgency of the project for the car maker suggested that short-term cost savings should not dictate the supply-chain strategy.

We suggest that several fundamental changes to the OEMs overall approach would have led to a significantly more successful program, and may have saved money in the long term.

1. Source two suppliers at the outset. Supplier 1 is a familiar supplier, close to home and very capable, and with a long track record with our organization. Guarantee that supplier a fixed volume of business in the program for its duration. Supplier 2 is the lower-cost but higher-risk supplier in Nanjing, China. Our supply agreement with this supplier reflects a more gradual ramp up as they develop the capabilities to supply this product on a consistent, reliable basis. Having Supplier 1 on board allows Supplier 2 to resolve any issues properly in a controlled, sustainable fashion and that prevents supply crises such the one that emerged here. As volume increases, Supplier 2 is able to carry more of the burden, and net costs on the project for that component are reduced for the OEM. In this case, we may have suggested that the same French Tier One supplier is responsible for both segments of component production, where Supplier 1 is their experienced facility in Illinois and Supplier 2 is their Nanjing operation. Let them manage the migration in production volume with an agreed, blended piece price for the component. This approach creates Agility in our supply chain, giving us the ability to react to increases in demand more quickly. If the French Tier One really wants to impress its customer, it can develop the ability to shift supply between two or three standardized facilities as exchange rates, shipping costs (related to the price of oil) and other factors change. At that point, they become Adaptive.

2. Spend the time necessary to understand the cultural and operational dynamics in China. This is an exercise that starts very early in our consideration of where to source the product. All countries and regions of the world do business a bit differently, at least, but developing business and executing high-risk projects in China requires well established guanxi networks of connections, trust, and relationshipsv. The guanxi network gets even thicker when you move to less-developed regionsvi. Respecting and engaging in this cultural dynamic is also critical to influencing where an international OEM’s project fits within Chinese supply chain priorities. One author’s organization started with some small tooling contracts on less important components of less critical projects to get to know the environment, the people and the practices. After completing several of these tooling projects, component supply for basic parts was started. The company was buying roughly $5 million per year in China before it sourced anything really strategic in the country. By that time, it had a sound understanding of what it took to be successful in China, but still applied robust risk management practices to that supply chain. Such a process assures that we have an Aligned supply chain, where our collective goals and objectives are similar.

3. Visibility is a simple and effective risk-mitigation tactic. Visibility here refers to the presence of cross-culturally trained leadership capable of generating the appropriate interactions and analysis at the right touch points in the project, and committing the necessary resources to support the developing supplier. Our presence is the best approach to minimize the impact of time, distance, communication and other risks on the project. In this case, we need to have technical and quality people on the ground in Nanjing as they develop their production processes for this project. We supervise prototype and pre-production builds together with our supplier. We go over good parts and bad parts together, and explain the difference. We may consider bringing several of their people to watch our operation in Illinois for several days to gain a broader perspective, and send people from Illinois to Nanjing. Stage-Gate reviews[4] are set up and supported to ensure the supplier’s capabilities are aligning with the production ramp up schedule.

Aspects of the Nanjing case were still evolving this year. Kai Chen eventually left Nanjing Automotive for another parts supplier, and his departure created further crises on the project. The OEM and Tier One supplier from France ultimately spent millions of dollars in expedited freight costs, line stoppages, sub-standard parts, travel and related expenses, all in an effort to source product in China, with the perceived low-cost supplier.

The old saying is ‘There is no free lunch’, and in this case it is true. The Chinese themselves take a very long-term perspective, and the OEM should have done the same thing. Will Nanjing Automotive become a capable and dependable supplier of high-tech components to the world’s automotive market? We believe so. Perhaps its growth has been accelerated by this project and its relationship with its French parent and North American customer. Then again, we might ask if the project could have achieved a higher degree of ‘launch smoothness’, as a colleague used to say. Absolutely.

[1] A Greenfield plant is a new facility, constructed on what was typically open land.

[2] Local, as in nearby the downstream assembly plant.

[3] Production in Nanjing was behind schedule, so the desired method of ocean transport would have been too slow, and the late parts would have shut down the vehicle assembly plant.

[4] Stage-Gate reviews are meetings scheduled at milestones in the project where cross-functional teams of leadership review key project deliverables

Reprint from Ivey Business Journal

[© Reprinted and used by permission of the Ivey Business School]