Standup Comedy is Finding Its Feet in India

There’s a new kid in town, and he’s making fun of you

“My friend Imran Ahmed said to me, ‘Man, Bal Thackeray dying is the worst thing he’s done—now the Swedish House Mafia gig is cancelled!’ I said to him, is that really the worst thing he could have done?”

This is a small stage in a 300-seater auditorium in a glitzy Mumbai mall, with spotlights on the speaker, a large laughing-mouth logo in the background. Instead of offended tigerish snarls and a broken head, the young man at the microphone gets a roar of laughter and applause, grins, and cheerfully proceeds to demolish other holy animals.

A little more than half a decade ago, that scenario would have been unimaginable. Most on-stage comedy was slapstick or, at most, poking fun at public figures through mimicry, performed by actors who peddled the same wares in the cinema. Hindi comedians found their spot on TV shows like the raucous Indian Laughter Challenge; Shekhar Suman did the talk-show route, with Movers And Shakers.

So what changed?

For one, in cities like Bangalore and Mumbai, with an established pub culture, electronic music nights and karaoke went stale and owners wanted something new and trendy to bring patrons through the door, particularly on slower weeknights.

Secondly, the online revolution brought comedic genius Russell Peters to our computer screens: Aha! It wasn’t just okay to poke fun at Indians, it was hilarious and cool!

Then, the Comedy Store came to India, providing a comfortable, up-market venue where Indian comics could perform alongside international acts, honing their skills and perfecting their sets. And more recently, the burgeoning Indian middle class (and their burgeoning wallets) attracted the Comedy Central channel to our TVs, bringing us even more high-quality stand-up.

And the cherries on top: The NRIs returning to desh as the West began to haemorrhage, and the expats whose companies had posted them in the new promised land, both of whom had seen Western-style stand-up abroad.

Of course, it needed performers too, and the first wave had mostly cut their comedic teeth abroad. Now they’ve been joined by—and some of them are actively mentoring—home-grown talent, and venues and event managers pursue them hotly. (One comic told us that there were more gigs than good performers.) All of them agree that the scene has grown because good venues now exist and audiences were ready—and ready to pay—to have taboos mocked rather than take offence.

Image: Dinesh Krishnan

In cities like Mumbai and Bangalore stand-up comedy acts brings in the patrons on slower weeknights

It’s still early days. There isn’t a particularly Indian style of stand-up; the British tend to do great vulgarity and satire, the Americans have observational geniuses, while most of our performers are somewhere in-between, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. There are very few women stand-ups (the ratios are as skewed abroad), and some of the aspiring talent at open mic nights seem to think just swearing on stage is funny. Even the more established names are still finding their niches, but as they do, some of them will truly become social commentators, holding up their mirrors to us and making us like it.

The Entrepreneur

Vir Das returned to India in 2004, after wowing the tough crowds of South Chicago where he went to university. Booed off stage 14 times in a row, the 15th time around he vented his anger and got a laugh. He’s not looked back since; he is now India’s most expensive stand-up act. He runs a company he named after the reason he left the USA, he jokes: The way Americans pronounced his name. “Weird Ass is a comedy hedge fund. Just like real hedge funds invest capital, we invest content into different things.” The eight members of his core team are all winners of open mic nights he organised, plus he has more than 60 associates across the country; together they lend their wit to movies, award show scripts, corporate events and song-writing. Though the film Delhi Belly put Das on the map, it is music that excites him most. His guitar-comedy act Alien Chutney is “filthy and fun, something that’s really caught on with college students”. However it’s not dirty jokes that sell out 2,000-seater auditoriums, but a “multimedia experience” that people pay Rs 2,000 to sit in the front row for. A History of India, Vir-ritten is his homage to his country; his set uses large screens and his sense of humour (a laugh every 14 seconds to be precise) to make his audience reflect on Indian history in a light-hearted way. The show has sold 90,000 tickets in the last 18 months. Das says that stand-up has exploded but it must be careful not to become another “flavour of the month” like pool parlours; like any fad, it will have to innovate to stay popular. And he’s betting his Weird Ass on being able to stay in the driver’s seat.

The Ambassador

The first thing Papa CJ told us was that comics shouldn’t be on a celebrity list: “Comedy is all grass-roots and anti-establishment. Being a celebrity is against its ethos.” CJ made his bones abroad: After an Oxford MBA and a lucrative day job in London, he decided to take a sabbatical and try stand-up. He went at it with a vengeance: In 10 months, he made 200 appearances at every open mic night and gig he could find in Britain. But it paid off: “Every event manager in the UK knew my name.” He returned to India—“I’ve always been a true desi at heart”—and began establishing himself in Delhi. He also helped create an ecosystem, organising what he thinks was India’s first open mic for comics in 2009. He plays up his Indian identity, which allows him to mock cultural stereotypes abroad. “Local humour won’t travel, but it helps build a connection at the start of a set,” he says, “and topical humour is almost universal, but won’t last, especially once it gets on TV.” Once he gets the audience laughing with him, he likes to wing it: “Comedy is a group psychology exercise where you’re looking to manage your audience. The best shows are 100 percent improvised, fluid interactions with the audience.” He says it takes 10 years to find your voice in stand-up. The Comedy Store is both a great venue, because of the supportive audience, and a terrible one… because of the supportive audience. Because one only learns from bad shows: “It’s important to grow in the dark, to make mistakes and learn.” Because it’s such a popular new art form, comics are instantly under pressure to perform and don’t have the freedom to experiment, which is something that worries him. He has performed alongside comedy greats like Russell Peters, has done over 1,000 shows around the world, and now runs his own stand-up company. The long haired Delhiite is very much the global face of Indian stand-up.

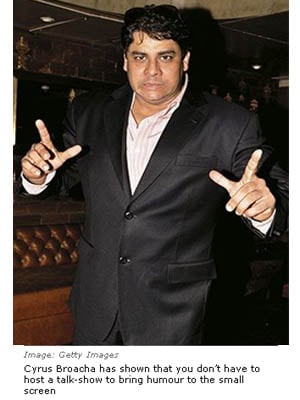

The Sit-down

“People are taking comedy seriously! What a pity!” Cyrus Broacha is arguably the most recognisable face in Indian comedy, but his stage is a faux newsdesk on TV. His hugely successful show, The Week that Wasn’t*, is political satire reminiscent of Jon Stewart. He’s shown that you don’t have to host a talk-show to bring humour to the small screen. “The Johnny Lever era is gone,” he says, and there’s a much larger market for stand-up comedy than five years ago, with the scene practically exploding in colleges. Broacha feels the Comedy Store has given a platform to amateurs. “I’d love to go but it’s far too expensive for me!” he jokes. Farhad Wadia, CEO of E18*, discovered Broacha as a precocious 12-year-old in theatre. He says Broacha is a youth icon but there’s space to grow. “He’s a big cricket fan; I see him combining comedy and cricket because that’s a big gap in Indian TV.” That brands are increasingly using comedy as a vehicle heartens Wadia: “It’s fun, and different, for Indian corporate events.” There’s simply more work for comedians now, says Broacha, “The class idiot is now making money!” He sees stand-up comedy being a viable career option for young people in three to five years.

The Part-timer

Anuvab Pal was a journalist in New York before he moved back to India to write for film and theatre. He auditioned for an open mic night at the Comedy Store in 2009 by accident. Back then there were four comics and an audience of 25. He’s now done 123 shows and sells out the 300-seater Comedy Store, even performing internationally three or four times a year. The Nation Wants to Know is his stand-out show and sells out in advance. His stage persona, the Cowardly Bengali, is all about being vulnerable and letting the audience share a connection, whether it’s talking about politics or trying to get your child into a Mumbai school. “It started in 2010 with a three-minute set. Now I do 90-minute shows, so what comes out is three-and-a-half years of my life, both professionally and personally.” He’s quit the day job now—“It’s been a challenge, leaving the corporate world and telling your parents you work in a mall!”—but eschews the corporate shows that are the bread-winners for most of the community, preferring to continue to spend his off stage time writing scripts and books.

* CNN-IBN (which runs The Week That Wasn’t) and E18 are part of the Network18 group, which publishes Forbes India.

Image: Dinesh Krishnan

Pal hopes standup comedy doesn’t go down the route of Indie music in the ’90s

Pal understands the significance of what’s happening: The Comedy Store has given English-speaking urban Indians a place to come and talk about things they’re not usually allowed to. He hopes stand-up comedy doesn’t go down the route of Indie music in the ’90s: After a brief period in the sun for the non-film musicians, Bollywood stormed back and took over the music channels. He sees stand-up comedy growing as the number of comedians increases, as top comics like Vir Das and Papa CJ branch out into film and theatre, and as Indian comedians refine sets that are universally funny, not just topical or local. “I think audiences in India are much cleverer than we give them credit for,” he says, “They will get all your references. Don’t think you’re smarter than your audience; you are the audience.”

The New Kids

Mumbai and Delhi aren’t the only cities with a thriving stand-up scene. Though the scale is smaller, Bangalore has seen its comedians grow just as fast. Sanjay Manaktala started performing twice a month in 2010 after he moved back to India from the USA. In 2011, he formed the Polished Bottoms troupe (with Praveen Kumar and Sundeep Rao, and later, Sal Yusuf). They started off doing gigs for free but now the same bars are courting them. They recently made the big jump to auditoriums, and sold 800 of the 1,000 seats at Chowdaiah Memorial Hall.

Manaktala’s persona is the NRI, Yusuf is the Brit, Rao does the northern humour and Kumar tickles the southern funny bone; they each offer something different and this hedging of bets has proven successful. “India is a bunch of countries mashed into one so there’s always material,” says Manaktala. He hasn’t quit his day job yet, but he’s doing 14 shows a month now. A quarter of his evenings are spent trying new material at open mic nights, another quarter are comedy nights at bars, a quarter on corporate gigs that pay the rent, and the rest are self-planned events at clubs and auditoriums.

Despite the frequency, there’s evidently a larger audience than he has tapped thus far: “I’ll do the same joke for three years and 300 people will come up to me and tell me they’ve never heard it before.” His goal is to refine his act so that he can send a clear message in two minutes, like Chris Rock and George Carlin, two comics all Indian stand-ups idolise. “In America you’ve got 300 million people and about 10,000 stand-up comedians. You’ve got at least 100 million people in India who speak English and know who Tom Cruise is, and we have 20 comics.”

The Impresario

Charlotte Ward, owner and manager of the Comedy Store in Mumbai, was brought up by her father around clubs and comedians. The daughter of Don Ward, owner of the iconic London comedy club, she brought the brand to India in 2010 and has been able to grow quickly.

It began as a place where Indian audiences could see the best British and American comics, with a local comedian as an opening act. Now, she firmly positions it as a space for Indian comics: “2012 was all Indian. We have 31 Indian comics who do 41 shows. We used to do five shows a weekend, now we have shows every night.” Two years ago, the Store was doing 23 shows a month including other productions. It’s now doing 44, more than the National Centre for the Performing Arts. The most remarkable thing is that at 4 pm on a weekday, they’ve usually sold less than 10 tickets and somehow by 8 o’clock it’s close to 200; a social media blitz puts bums in seats. The Store was sold out the last week of 2012 at Rs 600 a ticket.

Ward wants to expand into Hindi comedy through a pilot in February 2013. She says the future is taking Hindi stand-up to local theatres for Rs 40 a ticket. She is also looking to take her Indian comics to Dubai, Singapore and Sydney. “You don’t change a winning set,” she says, “You don’t bring your audience to the comedian; you take your product to new audiences.”

The real test for her comics is how they handle hecklers. Once they’ve learned to play a tough crowd, she can take them to the unforgiving stages of SoHo.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)