AirAsia India: Why did the pioneer of global low-cost aviation not live up to its potential in India?

With the Tatas buying out the remaining equity stake in the brand, the end of the runway seems near. But the airline has for long had a turbulent flight in India

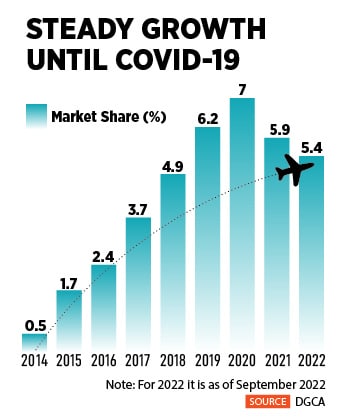

Headquartered in Bengaluru, AirAsia India has a market share of 5.9 percent, the lowest among all the low-cost carriers in the country, as of September this year. Image: Mohd RASFAN / AFP

Headquartered in Bengaluru, AirAsia India has a market share of 5.9 percent, the lowest among all the low-cost carriers in the country, as of September this year. Image: Mohd RASFAN / AFP

It was meant to be the stuff of dreams. A fledgling low-cost airline market with the world’s second-largest population, a pioneer in the global low-cost airline market looking to make inroads by taking on homegrown low-cost carriers and perhaps bring about a disruption, and a steely partnership involving one of the country’s best-known and most trusted brands. Yet, when it came to AirAsia India, the India arm of the Malaysia-based low-cost carrier, AirAsia, the flight was a turbulent one.

Today, the brand, entirely owned by the Tata Group, is all but waiting for curtains down as the group looks to merge its four airline brands in its attempt to fortify its aviation business under the Air India brand, which it acquired from the government last year. On November 3, Capital A, formerly known as AirAsia Group, said it is completing the sale of 16.33 percent equity it held in AirAsia India to Air India for Rs 155 crore in a no-profit, no-loss proposition. That had followed transactions in December 2020 and January 2021 to sell the stake that the Malaysian group held in the airline.

While the Tata Group had remained tight-lipped about a possible merger between the various brands, Singapore Airlines (SIA) said in October that it is exploring a potential merger of Vistara with Tata Group’s Air India. The group’s two low-cost carriers, Air India Express and AirAsia India are now entirely owned by the group, giving it enough leeway to merge them under one brand.

Campbell Wilson, the new CEO and managing director of Air India

Campbell Wilson, the new CEO and managing director of Air India

“Leaving aside the different airlines and different brands that sit under the Tata portfolio, what I see from an Air India perspective is the need for a full service and [a] low-cost proposition,” Campbell Wilson, the new CEO and managing director of Air India had told Forbes India in an interview in October. “So, our ambition is to build a world-class full-service carrier and a world-class low-cost carrier under the Air India Group and operate them synergistically.”

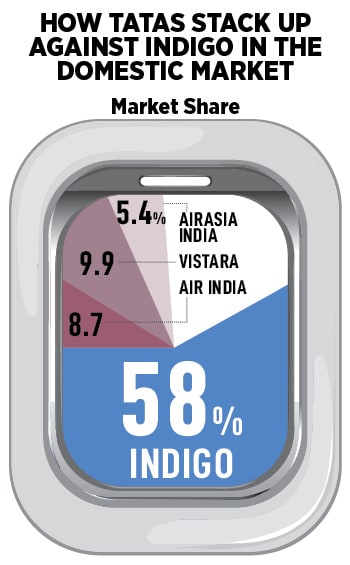

Headquartered in Bengaluru, AirAsia India has a market share of 5.9 percent, the lowest among all the low-cost carriers in the country, as of September this year. Even Vistara, which began operations around the same time as AirAsia India, albeit as a full service carrier, has a market share of nearly 10 percent. That, despite two of the country’s best-known low-cost carriers facing disruptions due to various reasons in recent times.

Headquartered in Bengaluru, AirAsia India has a market share of 5.9 percent, the lowest among all the low-cost carriers in the country, as of September this year. Even Vistara, which began operations around the same time as AirAsia India, albeit as a full service carrier, has a market share of nearly 10 percent. That, despite two of the country’s best-known low-cost carriers facing disruptions due to various reasons in recent times. The agency also filed a case against R Venkataramanan, managing trustee of Tata Trusts, and Tharumalingam Kanagalingam, the deputy group CEO (operations), of AirAsia, among others.

The agency also filed a case against R Venkataramanan, managing trustee of Tata Trusts, and Tharumalingam Kanagalingam, the deputy group CEO (operations), of AirAsia, among others. The Indian aviation market needs over 1,900 aircraft in the next 20 years to keep up with the growing demand for air travel. Aircraft manufacturer Airbus projects the 20-year traffic growth of India’s civil aviation sector at 7.7 percent, almost twice the world average of 4.3 percent. Domestic traffic growth is expected at 8.2 percent, one of the world’s highest.

The Indian aviation market needs over 1,900 aircraft in the next 20 years to keep up with the growing demand for air travel. Aircraft manufacturer Airbus projects the 20-year traffic growth of India’s civil aviation sector at 7.7 percent, almost twice the world average of 4.3 percent. Domestic traffic growth is expected at 8.2 percent, one of the world’s highest.