Announcing a tele-programme is not enough, India must take a more holistic view of mental health

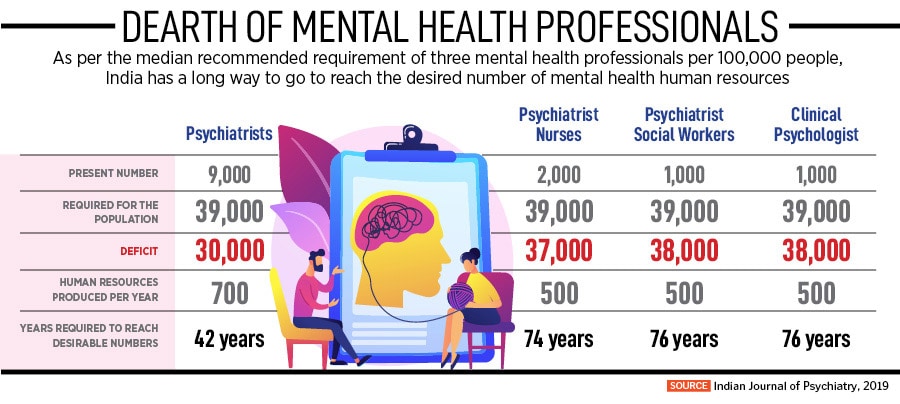

In a country where nearly 80 percent of people suffering from mental health issues do not receive treatment, it is important to focus on strengthening availability of skilled professionals and improving grassroots access to services beyond urban areas

Nirmala Sitharaman had announced the launch of a national tele-mental health programme, in order to provide better access to mental health counseling and care services

Nirmala Sitharaman had announced the launch of a national tele-mental health programme, in order to provide better access to mental health counseling and care services

Image: Arvind Yadav/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

On February 9, in a written reply to the Rajya Sabha, Nityanand Rai, Union minister of state for home affairs, said that 3,548 people had died by suicide due to unemployment in 2020.

He was quoting data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), which further suggested that during the same year, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, 5,213 people had died by suicide due to indebtedness and bankruptcy. In all, more than 25,000 people in India had died by suicide either due to unemployment or indebtedness between 2018 and 2020.

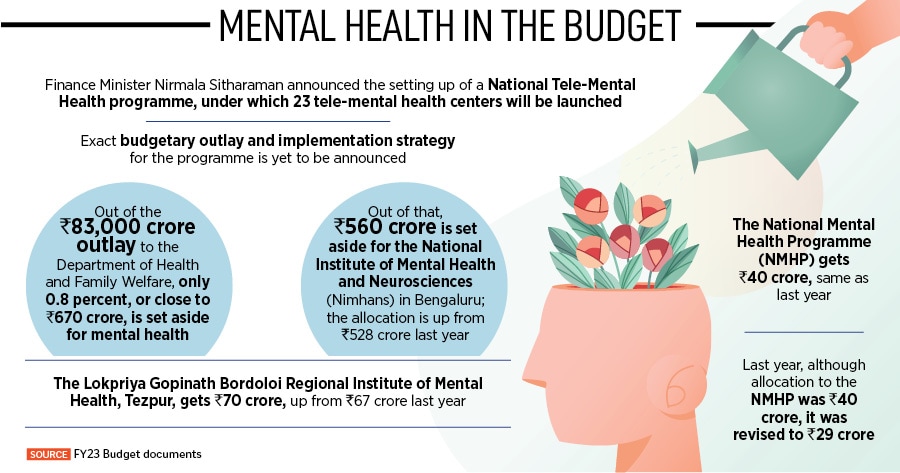

In the same written response, Rai stated that the government is implementing the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and supporting implementation of the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) in 692 districts across India in order to address the issue.

A few days ago in her Union Budget speech on February 1, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced the launch of a national tele-mental health programme, in order to provide better access to mental health counseling and care services. “The pandemic has accentuated mental health problems in people of all ages,” Sitharaman said, explaining the government’s intention to build a network of 23 tele-centres, with the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (Nimhans) in Bengaluru being the nodal centre, and the International Institute of Information Technology-Bangalore (IIITB) providing technology support. More details on the allocation for this tele-mental health programme and implementation strategy are yet to be announced.