Matilda Kullu: The purpose of saving lives

Grassroots health workers were instrumental in taking Covid-19 care to the bottom of the pyramid, but like Kullu, they remain overworked and underpaid

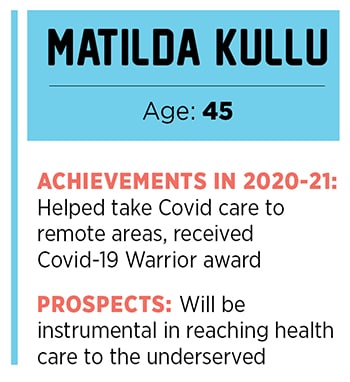

ASHA Worker Matilda Kullu

ASHA Worker Matilda Kullu

Every morning, Matilda Kullu, 45, starts her day at 5, finishing household chores, preparing lunch for the family of four and feeding the cattle before hopping on to her cycle to start her day with door-to-door visits. Fifteen years ago, Kullu was appointed as an Accredited Social Health Activist (Asha) for Gargadbahal village, in Baragaon tehsil of Odisha’s Sundargarh district. Kullu, who hails from the same village, looks after 964 people, mostly tribal, and is well aware of their health records.

In 2005, the government launched the National Rural Health Mission and recruited these workers to connect vulnerable communities to health care. There are over a million such workers in India.

When Kullu joined as an Asha, the villagers neither visited a doctor or a hospital if they fell sick—they rather performed ‘jhaad phoonk’ (black magic) to treat themselves. It took years for Kullu to educate the villagers to stop this and take appropriate medical routes. That’s not all, she even had to bear the brunt of casteism and untouchability during door-to-door visits since Kullu belongs to a Scheduled Tribe.

“It was really bad some years ago, things are much better now. People have become more understanding and less superstitious. The old generation still practises untouchability but that doesn’t bother me anymore,” says Kullu.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

With the onset of

With the onset of