ASHA workers: The underpaid, overworked, and often forgotten foot soldiers of India

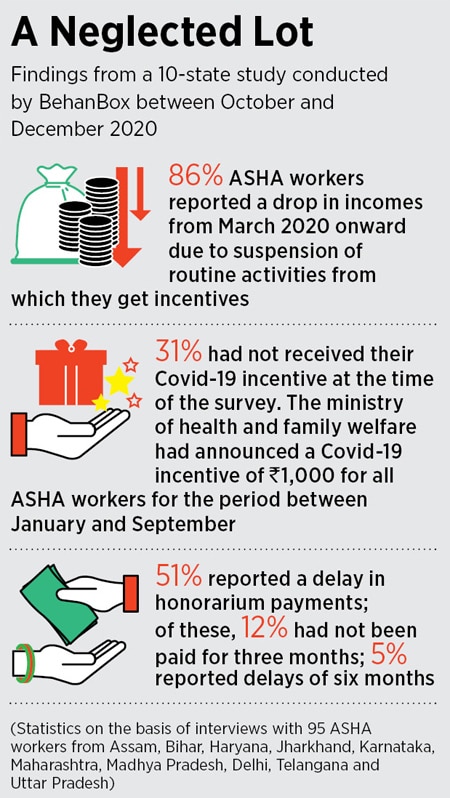

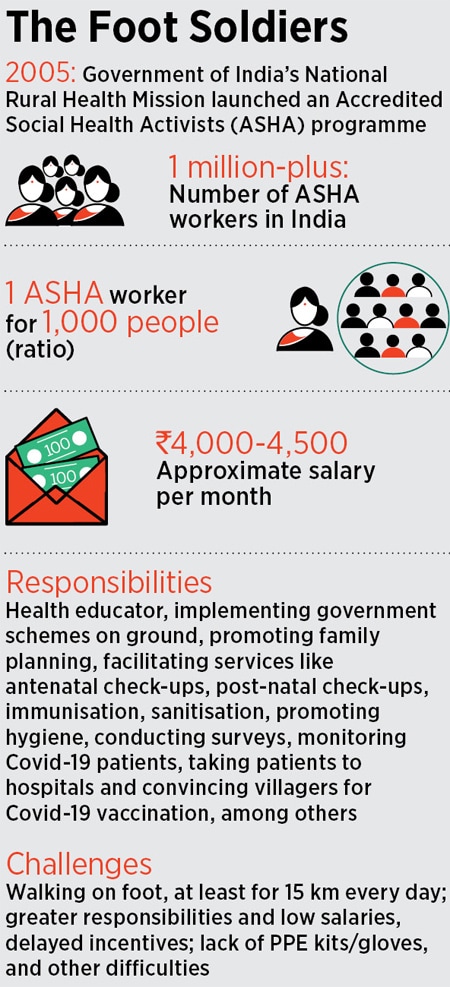

While doctors and nurses have been lauded during the pandemic, ASHA workers, who have been battling Covid-19 in rural India, are neglected. Will the overworked and underpaid health activists get the acknowledgment and respect they deserve?

Lakshmi Vaghela (right) is the only Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) for the Waghjipur village of 1,000 people in Gujarat

Lakshmi Vaghela (right) is the only Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) for the Waghjipur village of 1,000 people in Gujarat

Image: Naandika Tripathi

The sun beats down harshly on the deserted roads of Waghjipur village in Sanand, about 150 km from Ahmedabad in Gujarat. The occasional man walks around aimlessly at 9.30 am as we wait outside a blue, slightly dilapidated structure on a Wednesday morning. Minutes later, a lanky woman guides us inside the Waghjipur Anganwadi Kendra. “Hu Bharathi… Anganwadi worker, ASHAben aave che (I am Bharathi, the Anganwadi worker… the ASHA is on her way),” she says.

Immediately after, Lakshmi Vaghela rushes in, taking giant strides and gasping for breath. “Sorry ben, badhe chalta javu pade che (Sorry, I have to walk everywhere),” she says apologetically. Vaghela is the only Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) for the village of 1,000 people.

Currently, all ASHA workers have been instructed to focus on vaccines. So Vaghela, mother of two sons, wakes up by 5 am and goes around the village underlining the importance of vaccination to its inhabitants. “Initially when the vaccination drive started, someone who had taken a dose passed away. Since then, people have been scared. During our first vaccination drive, only four people turned up,” she recalls. However, since the second wave of the coronavirus, people have become more accepting of the vaccine. “But right now, there is a severe shortage,” Vaghela adds.

The pandemic has drastically increased the workload of ASHA workers. They have to go for door-to-door surveys and contact tracing, convince people to get tested, distribute essential medicines and ration, and stick Covid-19 seals on households, apart from carrying out other responsibilities.

(L-R) Nisha Taviyad, Pushpa Parmar, Soniya Hardikbhai Maheriya, and Manisha Maheriya are four of the six ASHA workers that look after Changodar village in Sanand, which has a population of 13,000 people

(L-R) Nisha Taviyad, Pushpa Parmar, Soniya Hardikbhai Maheriya, and Manisha Maheriya are four of the six ASHA workers that look after Changodar village in Sanand, which has a population of 13,000 people While working on the frontline during the pandemic, ASHA workers have often had to protest

While working on the frontline during the pandemic, ASHA workers have often had to protest

Vijithra is a 23-year-old ASHA who works with tribal communities in Karingari, Mananthavady

Vijithra is a 23-year-old ASHA who works with tribal communities in Karingari, Mananthavady