Can Narendra Modi's vaccine diplomacy help India win some lost ground in South Asia?

Though setbacks remain, it offers an opportunity to improve ties with neighbouring countries

India's ambassador Suresh Reddy, Foreign Minister Ernesto Araujo, Brazil's Health Minister Eduardo Pazuello and Communications Minister Fabio Faria prepare to receive two million doses of AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) from India, at Sao Paulo International Airport in Guarulhos, Brazil January 22, 2021.

India's ambassador Suresh Reddy, Foreign Minister Ernesto Araujo, Brazil's Health Minister Eduardo Pazuello and Communications Minister Fabio Faria prepare to receive two million doses of AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) from India, at Sao Paulo International Airport in Guarulhos, Brazil January 22, 2021.

Image: Amanda Perobelli/ REUTERS

It’s been a diplomatic coup of sorts. And, it certainly hasn’t gone down very well with China.

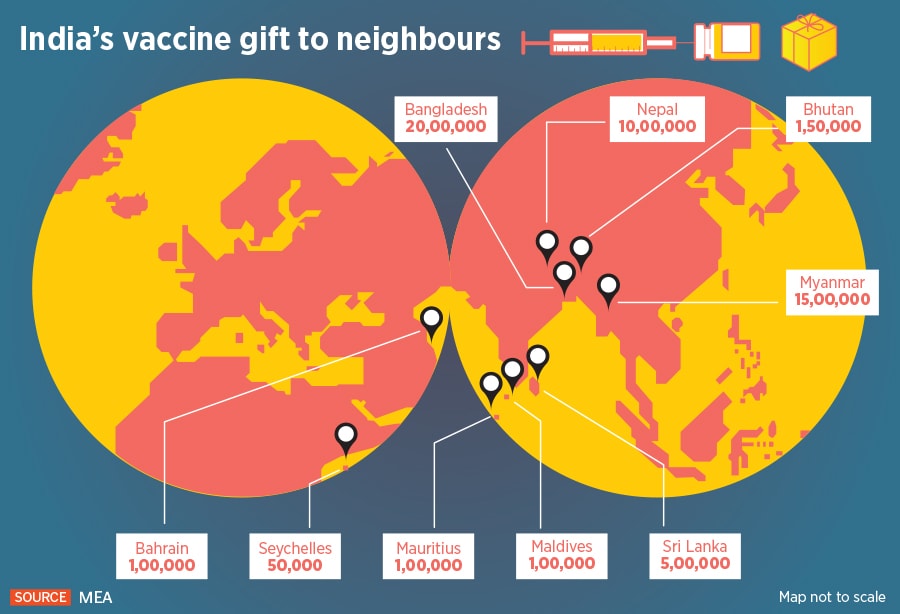

But that’s precisely what the Narendra Modi government could have expected after it unveiled Vaccine Maitri, an initiative to send millions of doses of the Indian manufactured Covid-19 vaccines to its neighbouring countries, and sometimes even as far as the Middle East and South America.

India had earlier supplied hydroxychloroquine, Remdesivir, and paracetamol tablets, as well as diagnostic kits, ventilators, masks, gloves, and other medical supplies to a large number of countries during the pandemic. This time, however, even as the country rolled out what’s touted as the world’s largest Covid-19 vaccination programme, it also deftly moved to send vaccines to neighbouring countries.

Quite importantly, the move also comes at a time when no other country has delivered free vaccines to other countries. Even the United States, where the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are being made, is yet to send vaccines to developing nations hit hard by the Covid-19 crisis.

“Immunisation programme is being implemented in India, as in other countries, in a phased manner to cover the healthcare providers, frontline workers and the most vulnerable,” India’s ministry of external affairs had said in a statement on January 19. “Keeping in view the domestic requirements of the phased rollout, India will continue to supply Covid-19 vaccines to partner countries over the coming weeks and months in a phased manner. It will be ensured that domestic manufacturers will have adequate stocks to meet domestic requirements while supplying abroad.”