Covid-19: India's second wave is here. And the world's largest vaccination programme may just not be enough

As India sets out to vaccinate people above 45, Forbes India takes stock of the pace of vaccinations, candidates under regulatory approval, vaccine-hesitancy, and the demand-supply dynamics

Image: Sunil Ghosh/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Image: Sunil Ghosh/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

India’s in the middle of a second wave of the Covid-19 outbreak. Over the past week, active cases in the country have been on the upswing, and daily cases have been crossing 50,000 regularly. The last time that happened was in October 2020, when India was emerging out of its first wave. Since then, cases had dropped significantly, even falling below 10,000 daily.

Over the last week, however, things have taken a turn for the worse. “After having successfully brought down the number of new Covid-19 cases from mid-September to February, India is now witnessing a rapid rise in cases,” health secretary Rajesh Bhushan said in a letter to the chief secretaries of all the state governments on March 30. “The current rise in cases is of concern and has the potential of overwhelming health care systems, unless checked right now.”

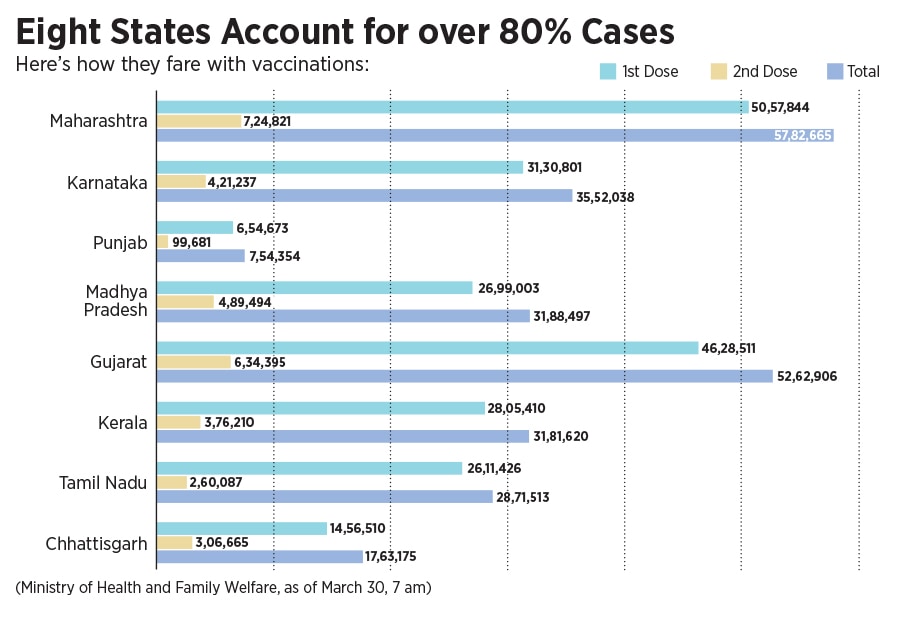

On March 28, financial capital Mumbai announced a strict night curfew, and the state government is even contemplating a lockdown in Maharashtra. Several other states have warned of and taken stringent measures, including curfews, to curtail the spread of cases. Currently, eight states account for about 80 percent of the cases, a number that is only expected to swell in the coming days. The central government has also identified urban clusters including Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru, as a cause of concern in the weeks ahead.

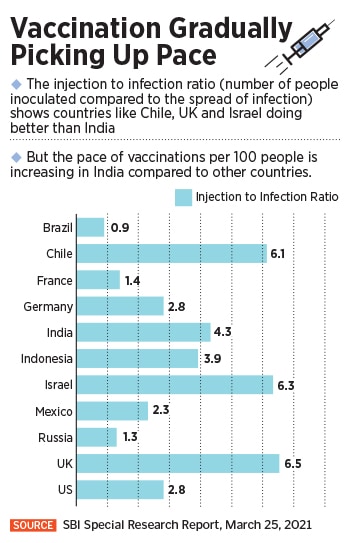

The worries have been corroborated by India’s largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), which has said in a report that India is witnessing a second wave beginning February 2021. “Considering the number of days from the current level of daily new cases to the peak level during the first wave, India might reach the peak in the second half of April,” says SBI in the report published on March 25. “The entire duration of the 2nd wave might last up to 100 days counted from 15th February.” That could very well mean the crisis isn’t likely to end before May.

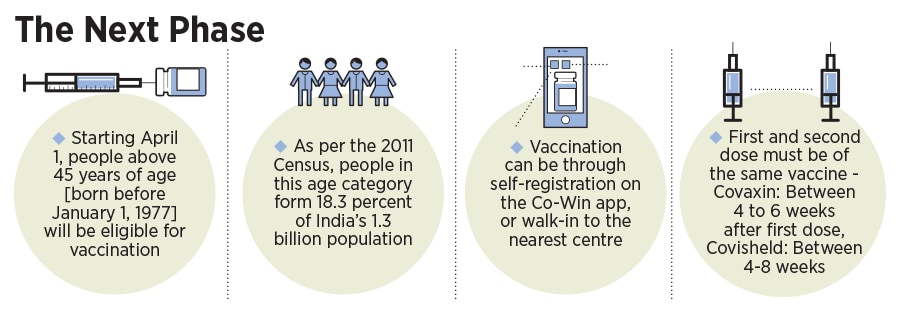

The second wave comes at a time when India has decided to make all its citizens aged above 45 eligible for vaccinations. So far, since the programme began on January 16, vaccines were only provided to those on the frontlines before it was extended to those above 60 years. On March 1, those above the age of 45, but with co-morbidities, were also allowed to vaccinate themselves. India has approved the use of Covishield, commonly known as the AstraZeneca vaccine, and the indigenous Covaxin, developed by Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech, currently to vaccinate its people.

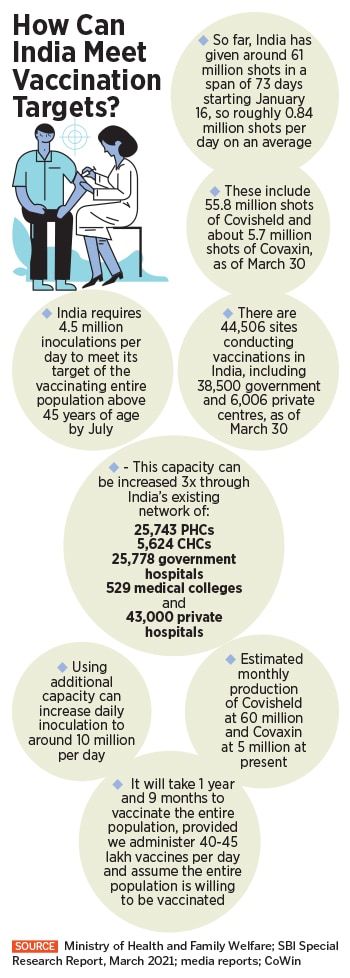

Yet, India is still vaccinating at less than 1.5 million doses a day across its 44,500 centres. A total of 63 million registrations have been received so far for vaccinations. On March 30, 1.29 million doses were administered, down from the high of 3 million on March 22.

Yet, India is still vaccinating at less than 1.5 million doses a day across its 44,500 centres. A total of 63 million registrations have been received so far for vaccinations. On March 30, 1.29 million doses were administered, down from the high of 3 million on March 22.

A November 2020 report from Credit Suisse says that India will need about 1.7 billion Covid-19 vaccine doses to inoculate the majority of its adult population. “India targets to administer 400-500 million doses by July-2021,” the report says. “In our view, there is sufficient capacity for vaccine manufacturing (>2.4 bn doses) and various components like vials, stoppers, syringes, gauze, alcohol swabs, etc.”

A November 2020 report from Credit Suisse says that India will need about 1.7 billion Covid-19 vaccine doses to inoculate the majority of its adult population. “India targets to administer 400-500 million doses by July-2021,” the report says. “In our view, there is sufficient capacity for vaccine manufacturing (>2.4 bn doses) and various components like vials, stoppers, syringes, gauze, alcohol swabs, etc.”

That has also meant that people have been shying away from taking the second dose after receiving their first one. For instance, out of 5-odd crore people who have received the first dose in India, only 89 lakh have received the second dose. In Telangana, where Dr Gorukanti’s hospital is located, the state health ministry on March 18 said that against 3 crore people who got their first dose, only 65 lakh people turned up for their second one. Dr Gorukanti believes this trend is reversing. “Initially, compliance for the second dose was low, likely due to the low and falling incidence of Covid cases in India at that time. However, Covid cases are rising again, and compliance for the second dose is significantly increasing,” he says.

That has also meant that people have been shying away from taking the second dose after receiving their first one. For instance, out of 5-odd crore people who have received the first dose in India, only 89 lakh have received the second dose. In Telangana, where Dr Gorukanti’s hospital is located, the state health ministry on March 18 said that against 3 crore people who got their first dose, only 65 lakh people turned up for their second one. Dr Gorukanti believes this trend is reversing. “Initially, compliance for the second dose was low, likely due to the low and falling incidence of Covid cases in India at that time. However, Covid cases are rising again, and compliance for the second dose is significantly increasing,” he says.