- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Game of IPOs: The sizzle and fizzle of internet companies

Game of IPOs: The sizzle and fizzle of internet companies

With stocks of tech startups underperforming on the bourses, here's a look at what caused the euphoria around them, and the subsequent collapse

Neha is a versatile financial journalist with over eight years experience in leading English business news channels. Her wide-ranging reportage includes impactful undercover investigations, multi-billion dollar deal breaks, and incisive coverage of key corporate and policy developments. She’s as comfortable anchoring live news on television, as she is writing insightful columns. She focuses on financial markets and global economy, moderates power-packed panels, and interviews influential industry leaders to get you the latest news, views and analysis of the stories that matter. She holds a postgraduate degree and specialisation certificates in the area of finance from global institutes. When she’s not fussing over inflation or balance sheets you may find her on a yoga mat in some beautiful part of the world. But she's always up for good coffee and interesting ideas.

- Market may not find it easy to climb unless earnings growth surprises materially: Invesco MF's CIO Taher Badshah

- Ancient Ayurvedic wisdom to new-age disruption, how 'Made in India' beauty brand Forest Essentials is going global

- Zomato's Blinkit has a great durable competitive advantage over Flipkart: Sanjeev Bikhchandani and Deepinder Goyal

- Quick commerce is the future: Info Edge's Sanjeev Bikhchandani and Zomato's Deepinder Goyal

- NPCI's Praveena Rai: Shaping India's payments landscape

Stocks of the dozen odd newly listed consumer internet companies have been trading at a hefty discount to their issue prices, as they face long and arduous paths to profitability, and their growth come under scrutiny

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Stocks of the dozen odd newly listed consumer internet companies have been trading at a hefty discount to their issue prices, as they face long and arduous paths to profitability, and their growth come under scrutiny

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

“These new-age tech companies were not ready for an IPO.”

“The IPO game was merely to get an exit for existing investors at a good price; no one really cared whether the valuation will sustain. In fact, they were almost certain that it wouldn’t.”

“Investors were valuing the market opportunity, not necessarily the business.”

Related stories

“These companies got listed at such expensive valuations only because of the growth potential, but now that’s a very big concern for the market because these companies have not been able to grow.”

“The bubble has burst.”

These are snippets of conversations with investment bankers, corporate lawyers, deal advisors, and industry insiders who Forbes India has interviewed. New-age technology growth stocks have vapourised on the bourses, leaving behind fumes of wealth destruction that cannot be pinned on turmoil in the global markets and economy. Often, greed and fear, not financial performance, drove the valuations of these beleaguered companies. But now the music has stopped and high-flying founders and investors are walking on ground again.

After the euphoria

Investment in Indian technology startups declined by 17 percent to $6 billion in the first six months of 2022. Their valuations in the private market has lost sheen, and public market investors have been taking chips off the table as losses deepen in equity holdings of digital stocks.

“The dismal performance of newly listed new-age tech companies has ushered in realism in IPO valuations. There was a lot of focus on revenue and market share, but now even private market investors are focussing more on cash flow and profitability,” says Ashish Bagadia, partner-corporate finance and investment banking, BDO India.

Also read: Tech companies price offerings aggressively, but non-tech issues more reasonable

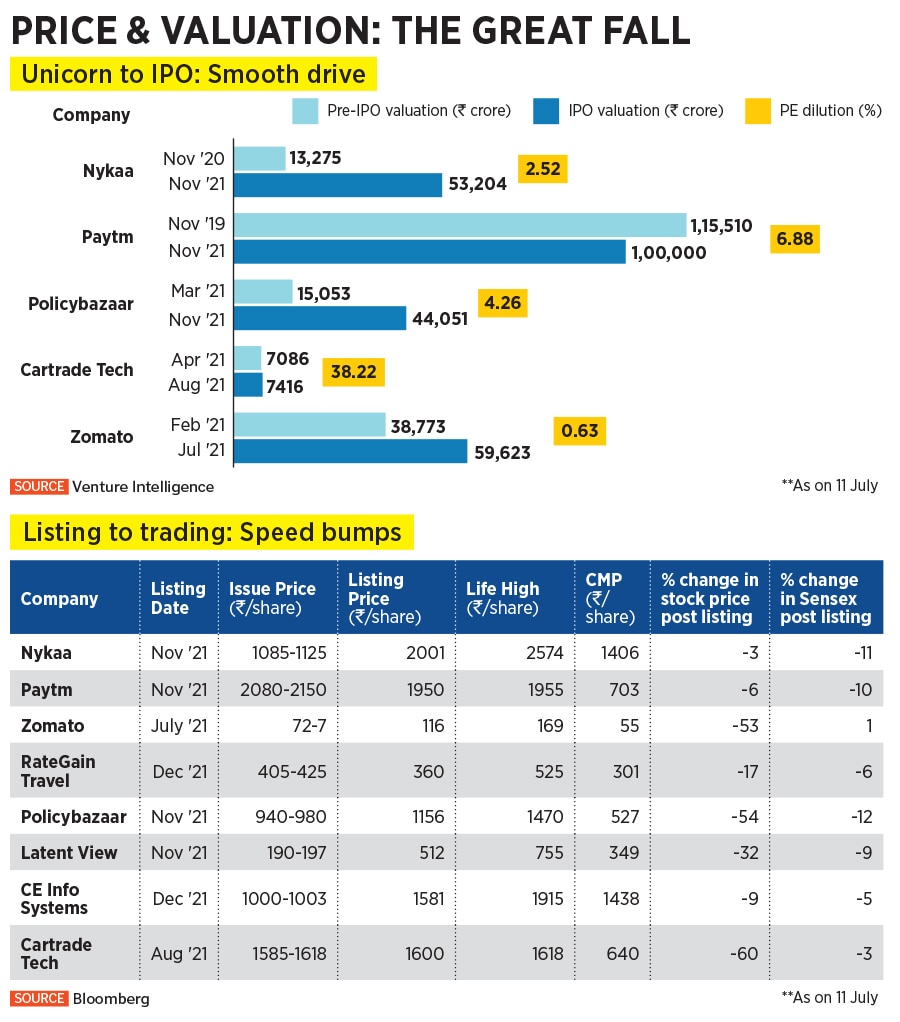

Stocks of the dozen odd newly listed consumer internet companies have been trading at a hefty discount to their issue prices, as they face long and arduous paths to profitability, and their growth come under scrutiny. “The capital market values businesses on fundamentals and not option pricing model of private markets. There is a fundamental disconnect in the financial profile of these companies and what capital market investors understand,” explains a banker, requesting anonymity.

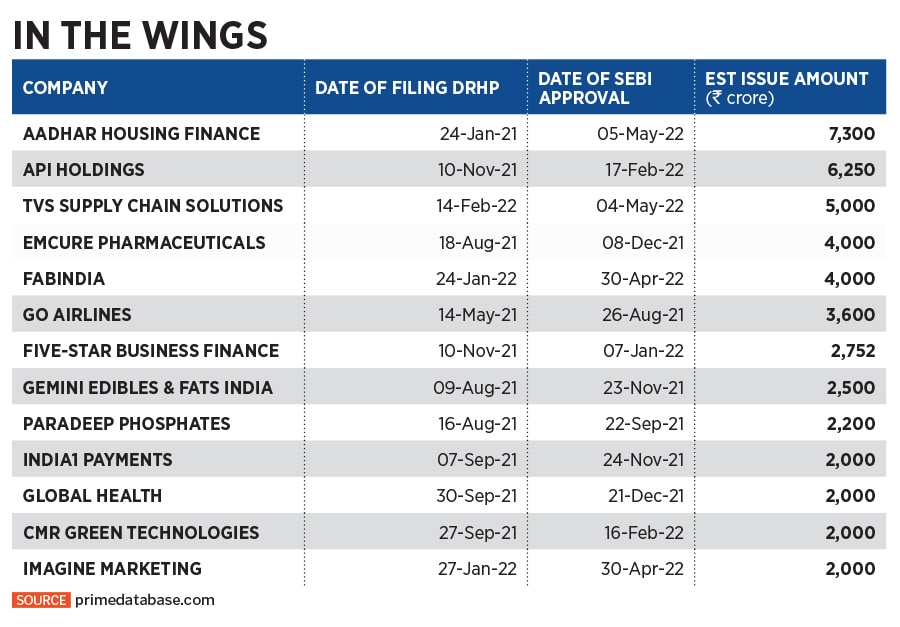

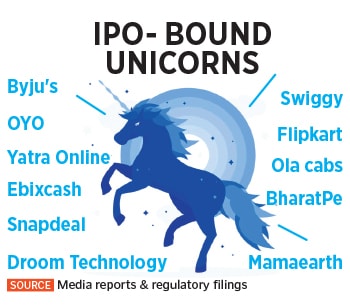

Tech startups that were eyeing a stellar stock market debut this year have now put their listing plans on hold. These unicorns have seen valuations drop by 15 to 30 percent, and intend to wait for market conditions to improve rather than reduce their offer price. Typically, private market valuations lag stock markets by 4 to 6 months, suggesting deeper price corrections.

Shaleen Sinha, head-growth tech india, Boston Consulting Group, says several tech clients were preparing for IPOs, but rising US interest rates and high inflation have pushed discussions to the back burner. “I definitely I don’t see much IPO activity happening for the next 2 to 4 quarters. Most of the companies we are working with are fairly well capitalised, so there is not much pressure to get into the market right now, and in a few cases money will be raised privately,” he says.

PharmEasy (API Holdings), Imagine Marketing (Boat) and One MobiKwik Systems are some such companies that have deferred their listings despite approvals from the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi). Others like ECom Express have stalled IPO plans due to market volatility. Thirty-eight companies, including Snapdeal, Droom Technology, Oyo, EbixCash and Yatra Online are awaiting Sebi’s approval for IPOs, but are said to be re-evaluating plans because valuations have significantly cooled off and, unlike a few months ago, there isn’t much appetite for new-age tech offerings.

“We saw these IPOs get subscribed 100-200x. People were not even looking at the business models; they were investing on the back of euphoria. They were outliers in terms of the amount of liquidity available, but if you fast forward to today and ask me if some of these tech companies would be able to go public today, I would cast my doubts,” says Shivam Bajaj, founder and CEO, Avener Capital.

Between January and June, of the 67 companies Sebi approved for IPOs, only 16 have tapped the primary market, in comparison to 24 during the same period last year.

“Companies that require capital for growth will be happy to take a cut on valuations and capture that growth to create overall value for all investors,” says the banker quoted earlier. However, companies that are eyeing IPOs mainly to provide profitable exits to existing investors, may put listing plans on hold since a high return multiple is the goal.

Valuations: The rise and fall

Throwing money at tech startups and pricing them at super high valuations has become the norm for venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) investors, say industry insiders.Valuation is not an exact science, a dealmaker emphasises, as he explains why early-stage investors focus on revenue as a guiding metric of financial performance and how valuations soar despite the absence of cash flow and profits. “Every six months the valuation of these companies would go up 3 to 6 times. I have raised $50 million for a company at a valuation of $400 million and six months down the line raised another $100 million at a $1 billion valuation,” says the banker.

Valuations are driven by overpriced rounds of buying the company’s equity at a steep sales ratio. Investors are in a race with rivals to close the deal and are willing to pay a premium, even at the cost of due diligence. Hedge funds that have entered the domain of VC firms have heavily stoked the exuberance in tech valuations.

Siddharth Mody, partner at law firm Desai & Diwanji, says there is tremendous peer pressure among PE players and a fear of missing out on good deals. “There is still an ask for exorbitant valuation that PE investors feel is unjustified, but if they take more time for evaluation there are other PE investors willing to invest in the company at the same valuation,” he says. “PE investors have a mandate from their investors. If they keep passing each opportunity, they will have a tough time answering to their limited partners.”

Bajaj agrees: “More than merchant bankers pricing the IPO, maybe PE investors should be more conscious about valuations and how they look at a business. This is one big reason why new-age tech companies are not performing well on the exchanges.”

Last year, US-based hedge fund Tiger Global closed 335 deals in the US and in China. But the meltdown in tech valuations has wiped out its gains and the firm’s portfolio is a sea of red. The fund has been at the forefront of investing in internet companies and its strategy of investing in the same company through separate in-house VC funds across different funding rounds lets it significantly raise the portfolio company’s valuation. This template has been widely copied by other VC firms, such as Softbank Vision Fund, which, after a series of multi-baggers, has a struggling portfolio as well.

Tiger Global has been among the main investors in several Indian startups like Flipkart and Zomato, and has been on an investing spree in India. In the first six months of 2022, it has increased its series A bets with investments of $402 million in 10 companies, versus a total of $75.7 million in 2021. Its investee companies include Battery Smart, Groyyo, Toplyne and Parallel Learning.

Alpha Wave, an offshoot of Tiger Global, has a $10 billion corpus and has been actively investing in Indian internet firms. For instance, in March 2021, it invested Rs 543 crore in PB Fintech at a pre-IPO valuation of Rs 15,053 crore; eight months later the company listed on the bourses at a valuation of Rs 44,051 crore, allowing Alpha Wave to exit with a high return multiple. The stock now trades more than 50 percent below its listing price of Rs 1,156 per share.

“The more valuable a founder makes each share, the less dilution he will suffer. [With a higher valuation in each subsequent round] the promoter is very happy because he has to consequently suffer a lower amount of dilution by selling fewer shares at a higher value,” says Xerxes Antia, partner, BTG Legal.

Disclosures

For pricing an issue, most merchant bankers depend on the information the company provides. The recent rout has raised questions on the pricing and valuation methodology. “A banker has the mandate to ensure the IPO happens at the best valuation; it is a judgment call based on various market factors. Can we question the banker if the law allows them to make a judgment, unless of course there’s apparent fraud?” says a dealmaker requesting anonymity.Mody highlights the need for better disclosure norms that can be readily accessed without reading bulky and complex offer documents. “Sebi must relook public market disclosure requirements. We need upfront and relevant information like net profit, loss for last three years,” he says.

Discretion plays an important role. For example, an internet company may claim to have 1,000 subscribers, but in reality only 100 of them may be regular users; the other 900 could be using the services only when there is an attractive discount.

“Often bankers may know it is an exaggerated number but no parameters are defined. Most merchant bankers have a very big disclaimer, saying the analysis is on the basis of information provided to them. This information is coming from the company, and the management wants to maximise valuation. It’s a circle,” adds the dealmaker.

After the recent IPO debacle of some tech companies, Sebi has stepped in to tighten their disclosure norms. Markets frowned upon the fact that promoters and founders were rushing loss-making firms into capital markets ahead of their time, and dumping their shares in the primary market to earn handsome returns for themselves and early investors, while leaving public shareholders with huge losses.

The fact that these companies are trading much below their issue prices is a cause for concern. Retail investors are sitting on a pile of losses, and there is a need for better understanding of the variance in valuation metrics in comparison to traditional companies.

Previously, in an attempt, to safeguard the interests of retail shareholders, Sebi had extended the lock-in period for anchor investors to 90 days; the existing lock-in of 30 days would continue for 50 percent of the portion allocated to anchor investors, and for the remaining portion, a lock-in period of 90 days will be applicable for all issues opening after 1 April, 2022.

For promoters, the lock-in period was reduced from three years to 18 months for allotments up to 20 percent of the post-issue paid-up capital. For allotments exceeding 20 percent, the lock-in period was reduced from one year to 6 months.

In context

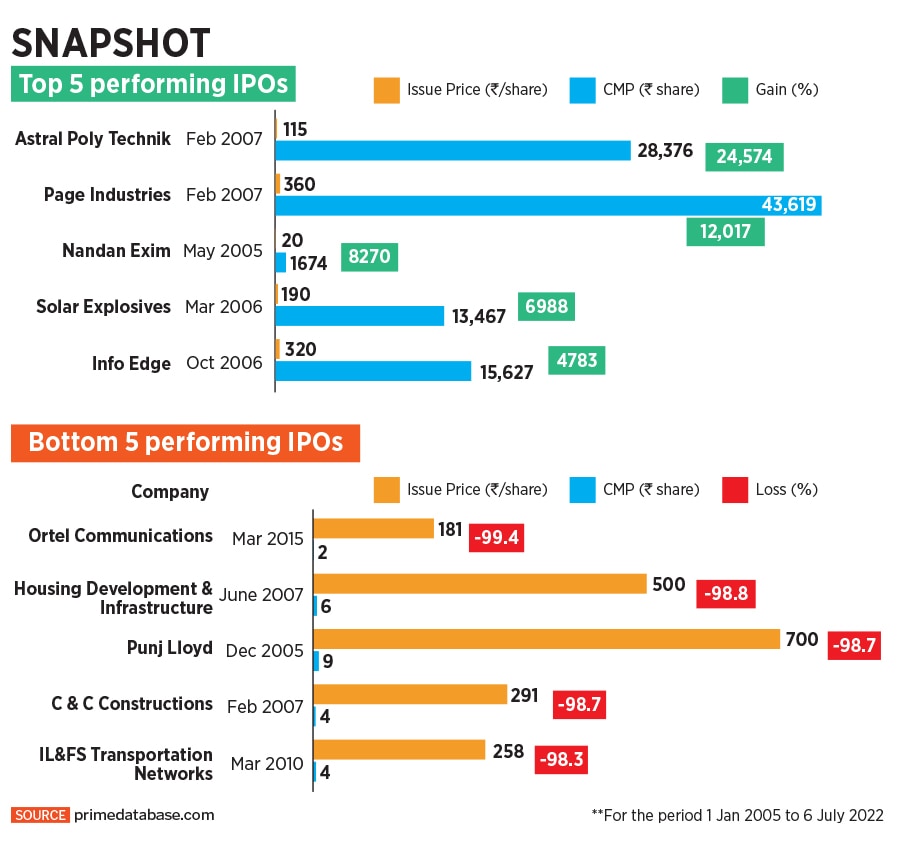

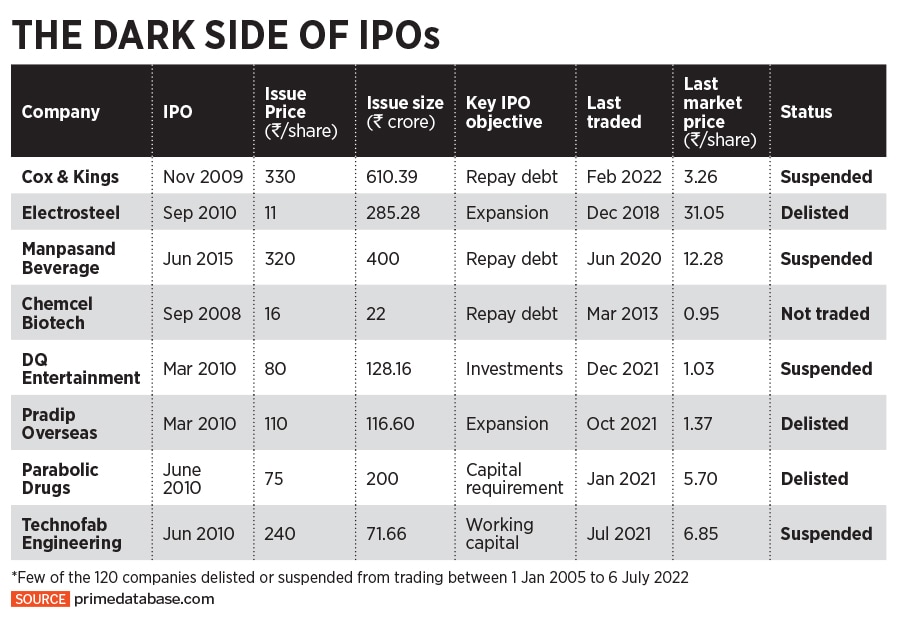

Historical data suggests that the timings of IPOs do not have a bearing on the stock’s long-term performance. Although the listing gains set the tone, they do not determine the returns over the following decades. There are companies that hit the markets during periods of turbulence, but over the following two decades emerged among the best performing IPOs. The opposite is also true.Since 2005, according to Prime Database, 501 companies got listed on the exchanges in India, while over 120 got delisted or were suspended from trading, or do not exist. In most cases, the delisting or suspension took place a decade or so after the company’s IPO; their final share price often less than a tenth of the issue price.

“Many companies list without realising the substantial disclosure requirements that need to be followed, with no margin for error. They struggle to meet compliance requirements and sometimes end up with regulatory issues,” Bagadia says.

In several cases, companies tapped capital markets to repay debt, but years later found themselves embroiled in charges of misgovernance and fraud. Dozens of these companies have been referred to National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) for insolvency and bankruptcy proceedings. Some recent examples include ABG Shipyard, Lanco Infratech, Electrosteel Castings, Manpasand Beverages, and Gitanjali Gems. Often, stocks have been suspended from trading and delisted due to non-compliance issues. But many times, firms have opted for delisting due to lack of interest of market players.

Buyers beware

With regard to recent tech IPOs, retail investors have been rushing in where angels fear to tread. “Now, with these companies giving negative returns, there is no appetite for wealth managers to push these IPOs or recommend these stocks to their clients,” says the banker.Investing directly in markets warrantees a certain level of involvement and understanding of the business, management, and valuation. How many retail investors can claim to have read 2,000-plus pages of Draft Red Herring Prospectus (DRHP) filings?

Several of these listings were mispriced and launched ahead of time. Even seasoned fund managers are trying to get a grip on the astronomically high valuations and business metrics of internet companies, since they are different from traditional companies.

“As many of these companies are new, it takes time for the market to understand each of these variables. IPOs generally get clubbed when the market sentiment is bullish, and thus valuation may not be favourable,” says Neelesh Surana, CIO, Mirae Asset Investment Managers, cautioning retail investors against direct exposure in primary and secondary markets. “While professional fund managers can also make mistakes, the risk-adjusted returns in terms of position, sizing, etc, are not as bad. Also, they are more driven by facts than emotions, and can constantly review [the stock in terms of] current price versus value.”

Unless investors are looking for trading gains on listing day, it is better for long-term investors to minimise risks and wait for the frenzy to settle. As we have seen over the past one year, once the euphoria ends, and sanity emerges, public shareholders can get a more realistic picture of the company’s financial performance and long-term growth potential.