How SRF is transforming itself into a speciality chemicals player with global ambitions

Arun Bharat Ram's sons are determined to not make the same mistakes as other family businesses. With eyes on the global market, they are stewarding the ship

Sons Ashish (left) and Kartik Bharat Ram are now the stewards at SRF Limited, where the increase in market capitalisation over the last six years has catapulted Arun Bharat Ram (seated) to the billionaires list

Sons Ashish (left) and Kartik Bharat Ram are now the stewards at SRF Limited, where the increase in market capitalisation over the last six years has catapulted Arun Bharat Ram (seated) to the billionaires list

Image: Amit Verma

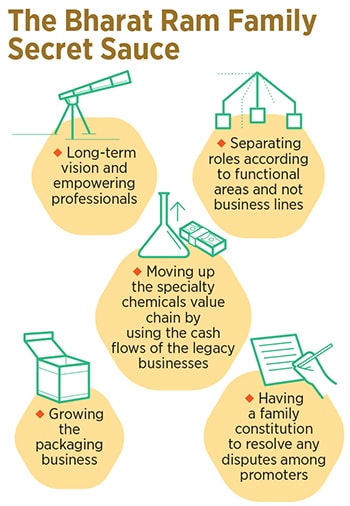

Amongst the first points that Kartik Bharat Ram makes, as we settle in for our interview, is their steadfast intention to avoid a repeat of what they have seen in several business families: Sibling rivalry resulting in a split. Indian business history is littered with founding families destroying promising businesses. The Bharat Ram family saw its own business split in 1999. Arun Bharat Ram’s sons are clear they don’t intend to go down that path.

It’s plain to see why. They’d clearly have a lot to lose. Since taking over SRF, or Shri Ram Fibres as it was then known, as part of a family spilt, this branch of the Bharat Ram family has built a business that is valued at ₹35,000 crore. One of their lines—specialty chemicals—has immense growth potential. Another business, refrigerant gases, too has a promising future as India’s cooling needs grow. The increase in market capitalisation that has taken place mainly over the last six years has catapulted chairman Arun Bharat Ram, 80, worth $1.8 billion, to the Forbes Billionaires List. Sons Ashish, 52, managing director and Kartik, 49, deputy managing director, are now the stewards of this business.

Equally theirs is a story of efficient capital allocation, long-term thinking and the benefits of a diversified revenue and profit stream. These businesses have taken decades to put together and their durability is sticky. That is one reason why the market is valuing it at a 35 price to earnings multiple even though a part of their profitability comes from legacy businesses with poor growth potential. In the year ended March 2020 SRF had revenues of ₹7,209 crore and profits of ₹1,019 crore. Its return on equity capital was at a decadal high at 21 percent.

The brothers, after having taken the business this far, are about to embark on a new and potentially more exciting phase. SRF is now on track to produce a significant amount of free cash flow. What Ashish and Kartik do with this is likely to shape their legacy. A part of it will be returned to shareholders based on feedback they’ve received from the investor community. Over the past 18 months the company has returned nearly ₹200 crore.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

In those licence raj days business decisions were made based on the licences granted and in the 1980s the group got permission to produce flourochemicals that go into refrigerant gases. While India was still a small consumer, the view was that this consumption would grow. In 1987 the Montreal Protocol mandated the phasing out of chloroflourocarbons (CFCs) and the company found itself staring at a loss in business.

In those licence raj days business decisions were made based on the licences granted and in the 1980s the group got permission to produce flourochemicals that go into refrigerant gases. While India was still a small consumer, the view was that this consumption would grow. In 1987 the Montreal Protocol mandated the phasing out of chloroflourocarbons (CFCs) and the company found itself staring at a loss in business.