- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- How Tata Advanced Systems Limited is advancing the Tata group's aerospace and defence dreams

How Tata Advanced Systems Limited is advancing the Tata group's aerospace and defence dreams

TASL, in partnership with Airbus, is gearing up to become India's first private manufacturer of a military aircraft, and will make 40 Airbus C295, a new-generation tactical airlifter that's meant to replace the ageing fleet of the Avro Hawker Siddeley HS-748

Manu Balachandran is a writer for Forbes India, based in Bengaluru. At Forbes India, Manu writes on automobiles, aviation, pharmaceuticals, banking, infrastructure, economy and long profiles among many others. He also moderates many of Forbes India's CEO and CXO events and hosts Capital Ideas, a podcast on the most riveting success stories from the business world. He has previously worked with Quartz, The Economic Times and Business Standard in Mumbai and New Delhi. Manu has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University and a degree in economics from the Loyola College. When not chasing stories, he is most likely obsessing over Formula 1 (Read: Lewis Hamilton), historical events and people, or planning long weekend drives from Bengaluru

Sukaran Singh, CEO and Managing Director of Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL); Image: Mexy Xavier

Sukaran Singh, CEO and Managing Director of Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL); Image: Mexy Xavier

It all started with what Sukaran Singh describes as a blank paper, with nothing but the Tata name on it.

The year was 2007, and the Tata group was riding the wave of its famed buyout of Corus Steel in the UK and gearing up for the blockbuster launch of the Tata Nano, the widely-anticipated poor man’s car. The group under Ratan Tata had already bought out UK-based Tetley and emerged as the frontrunner to acquire Jaguar Land Rover from Ford Motors, all while building up a stellar reputation as a formidable global conglomerate.

Related stories

That’s perhaps why Ratan Tata—whose obsession with everything aviation is no secret—knew the timing was also apt for the 155-year-old group to foray into newer frontiers, particularly in building aerospace and defence capabilities. Discussions had been going on at Bombay House, the headquarters of the salt-to steel conglomerate, since 2006 for an entry into the largely-government-controlled defence and aerospace manufacturing sector.

But there were two problems. Make in India, unlike today, was not a buzzword then, which meant investments could turn out to be risky, especially when it came to procurement. Then, even as the Tata group made everything from salt and steel to cars and even ran hotels, it had nothing to show on defence or aerospace engineering. The only exception, perhaps, was some expertise in manufacturing trucks for defence and operating an airline, Air India, before the government swept in and took over control of that in the 1950s.

“Initially, we had nothing,” says Sukaran Singh, CEO and managing director of Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL), the company that today leads the Tata group’s play in aerospace and defence manufacturing. “We just had a piece of paper and the Tata brand name when we had to get contracts.” TASL was set up in 2007, and in two years, struck a deal with Sikorsky Aircraft, then a subsidiary of United Technologies Corp, to make aerospace components in India, followed by another long-term contract to assemble Sikorsky S-92 helicopter cabins.

“The first ones [contract] we got were with people like Lockheed Martin to build what is called the Empennage of the C130J,” explains Singh. “We also got the first deal, which is the S92 helicopter, a helicopter for VVIPs.” Under the deal with Sikorsky, which would later be purchased by Lockheed Martin, TASL would manufacture the cabin for helicopters that were widely used by VVIPs across the globe, including the US president.

“He (Ratan Tata) was the one who actually had the initial relationships, built that credibility with them (foreign companies), and told them that we can do it,” adds Singh. “And it was because of his trust in our team that we could execute it.”

Since then, TASL has come a long way. The Mumbai-headquartered company is now gearing up to become India’s first private manufacturer of a military aircraft, to be built in India. The company, in partnership with Airbus, will make 40 Airbus C295, a new-generation tactical airlifter that’s meant to replace the ageing fleet of the Avro Hawker Siddeley HS-748 twin-turboprop aircraft, that has been in service with the Indian Air Force since the early 1960s.

The deal between TASL and Airbus to sell the aircraft, worth Rs21,000 crore, was signed and approved by the Indian government in September last year. Airbus will sell 16 aircraft in fly-away condition within four years while the remaining 40 will be manufactured and assembled by TASL in its new facility in Vadodara, Gujarat. Additionally, TASL will also provide MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) support and service for the 56 aircraft, which by itself provides an avenue for future revenues.

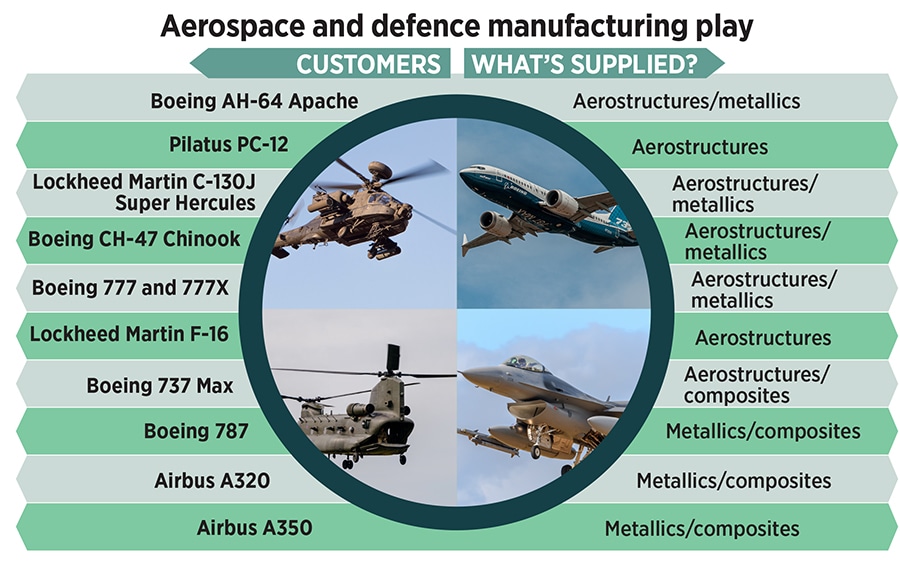

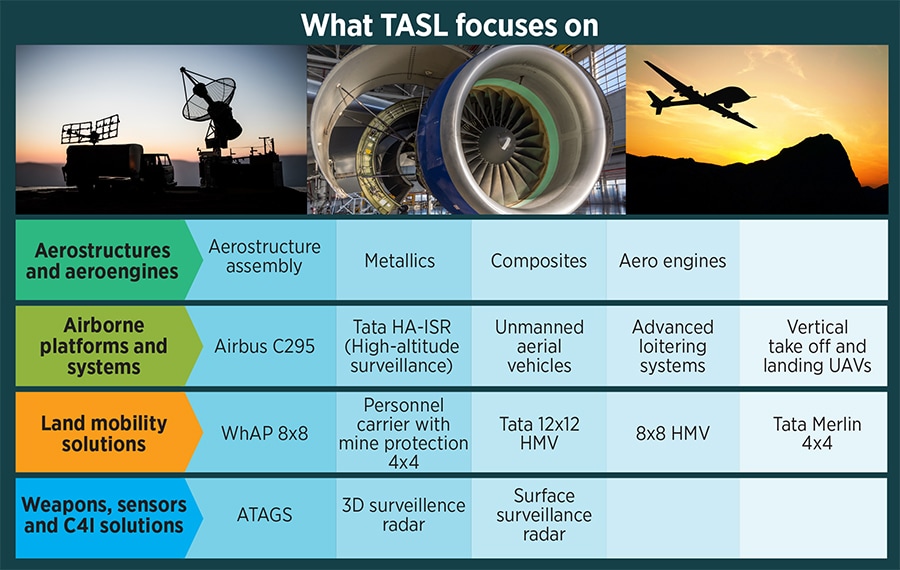

That’s a giant leap for the 16-year-old defence and aerospace manufacturer, who had been steadily building up a business that now spans four segments. There is the aerostructures and aero engines arm that manufactures metallics, engines, and composites for aircraft and helicopters, an airborne systems and platforms that manufactures aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), a defence arm that manufactures weapons, radars and sensors, and a combat land mobility arm, which manufactures armoured platforms and vehicles.

“We are certainly trying to build on the 150-year-old theme of the Tata group in how we can lead in areas, and not follow, and by taking good risk in areas which are nation-building,” Singh says. “And to do it all while remaining profitable and ethical.”

“Just like its parent company, which has a presence in almost all commercial domains, TASL has made its presence noticed in all three broad defence domains of airborne, naval and land systems,” says Sourabh Banik, project manager, aerospace and defence at London-based consultancy firm GlobalData. “It has certainly established itself as a major defence player within India by bagging many contracts awarded by the country’s ministry of defence, either as a prime or as a sub-contractor.”

Also read: Make in India: How HAL is gearing up to deliver

From Nothing

“Essentially, TASL is an interesting example of a startup within a corporate because there was nothing when it started,” Singh says.The idea to build a defence business was broadly based on two considerations. One was to develop capabilities in aerospace and defence with exports in mind with an eventual long-term view of offering the capabilities to India, while simultaneously focusing on technology which cannot be accessed from abroad.

“It was at a time when no one thought about it,” Singh says. “The then-chairman (Ratan Tata) said we must make these investments as a start towards building aircraft and helicopters for foreign companies, and to build technologies that foreign companies would not give to India. This strategy of developing capabilities by addressing markets abroad, and by developing own technologies, even without orders, really came from him.”

In 2009, India introduced a new rule that made it mandatory for foreign defence firms to source 30 percent of their equipment locally to boost the domestic defence sector. Before that, in 2005, India adopted the Defence Offset Policy for capital purchases above Rs300 crore which made it mandatory for foreign vendors to invest at least 30 percent of the value of the purchase in the country.

By 2009, the Sikorsky helicopter deal was in place, followed by a partnership with Lockheed Martin, which was due to sell the Hercules C130-J aircraft in India. The partnership was to manufacture aerostructures for the C-130J aircraft. Over the next few years, apart from Sikorsky and Lockheed Martin, the company went on to stitch partnerships with global original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), including Pilatus Aircraft Ltd, Cobham Mission Equipment, and RUAG Aviation. Alongside, the company also began working on ramping up its offerings in radars, missiles and even UAVs.

By 2014, Singh, who had been with Tata Sons since 2003, was roped in as CEO of the company. He stepped in a few weeks after TASL partnered with Airbus Defence and Space, a division of Airbus Group, to bid for Indian Air Force's transport aircraft replacement programme. It’s another story that the joint venture (JV) took another seven years to get approvals from the government, indicating the extent of the challenge for private sector players in the sector.

Healthy Mix

Today, TASL’s business comprises four arms. The aerostructure and aero engines one is almost entirely focussed on export to global defence companies, including Boeing, Airbus and Lockheed, where it manufactures wings, fuselage, and empennage, among others. “We build aircraft and helicopter parts, as well as aero engine parts,” Singh says. The manufacturing is done out of the company’s facilities in Hyderabad and Nagpur, and TASL also provides parts to commercial airliners, including the Boeing 737 Max and the Airbus A320.At the company’s airborne platforms and systems division, much of the focus is on local manufacturing and final assembly of both aircraft and helicopters. That includes the Airbus C295 aircraft in addition to a proposal to manufacture F21 aircraft in India in partnership with Lockheed Martin. India is expected to seek a proposal for 114 multi-role fighter aircraft worth $20 billion, sometime this year, and the JV is gearing up to tap that contract. In addition, the arm also manufactures radars and UAVs.

The company’s defence division, based in Bengaluru, manufactures missile launchers, rocket launchers and optronics, and has also developed ATAGS (Advanced Towed Artillery Gun System), an Artillery Gun System, in partnership with DRDO. The arm also manufactures electronic warfare systems and communication systems in addition to cyber security solutions. The arm had recently developed the country’s first vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) loitering munition capable of launching missions up to a distance of 50 km, with real-time targeting, either by the operator or autonomously.

Then, there is the land mobility business based in Pune, where it manufactures tactical and combat support vehicles in addition to logistics and light armoured vehicles. Recently, its LPTA-244 trucks were sold to the Moroccan Army.

“Under one roof, we have a very varied engineering capability,” Singh says. “We have, among all the divisions, focussed on activities which are not necessarily being developed in India. We may be the only one or the second company doing that. And in some areas, we are doing things that I know no one else is even attempting. And these are the areas where technologies were denied to India by foreign players, and which we have taken the onus of developing on our own.”

Also read: Why India's defence sector is booming

Ramping Up

Over the past few years, TASL has also sharpened its focus on the defence sector by consolidating numerous defence arms under the Tata group into its fold to create a large defence monolith within the group.“TASL, the flagship company of the Tata group in the defence segment, continues to receive strategic and financial support from TSPL (Tata Sons Private Limited),” ratings agency India Ratings said in a report in December last year. Between 2011 and 2022, Tata Sons infused equity worth Rs2,279 crore for funding acquisitions, capex and for funding upfront losses during the stabilisation phase of the new facilities, set up with numerous JV partners.

“The capital infusion, along with the continuous managerial supervision, has helped TASL in maintaining healthy associations with global partners in terms of attaining extensions in its existing orders, as well as entering into new JVs with other reputed global companies,” India Ratings said in its report.

It also helped that since taking charge as chairman of Tata Sons in 2017, N Chandrasekaran was instrumental in pushing the consolidation in an attempt to engage holistically with the company’s customers spread across geographies. Group companies such as Tata Power SED, TAL Manufacturing, Tata Advanced Materials and the defence division of Tata Motors were brought under the TASL fold by 2018. “The ability to consolidate all the different Tata companies in aerospace and defence into one entity came through our current Chairman’s initiative,” Singh says. “He has been very supportive and strategic.”

Today, TASL counts industry veterans, including Vijay Singh, the former defence secretary of India, and NAK Browne, the former chief of the Indian Air Force, as its board members. Banmali Agrawala, a former president and CEO of GE South Asia, the American conglomerate, serves as director for infrastructure at TASL in addition to serving on the board.

“Prior to these acquisitions, due to the fragmented nature of the defence business, Tata as a group was not giving the best value to the customer,” Singh concedes. “These other companies were mostly owned by publicly listed companies. Some were owned by Tata Power, some by Tata Motors and so on, and over the last three to four years, we have consolidated these different companies.”

But the company’s biggest turning point came in 2021 when the government of India approved a deal that would see TASL manufacturing the Airbus C295 aircraft in the country. “At the end of the day, we're going to make a full aircraft from the metal all the way to flying an aircraft,” Singh says. India announced plans to acquire 56 C295 aircraft in September 2021 to replace the Indian Air Force’s legacy AVRO fleet. The first 16 aircraft will be assembled in Seville, Spain, and delivered in ‘fly-away’ condition.

“In certain areas, we do what is called ‘Build to Print’, like the C295,” Singh says. “It’s someone else's design, but we are getting the manufacturing, and it is obviously next best to design-to-manufacture. But manufacturing very importantly allows you to build the ecosystem, which is essential.”

The C295 is the first big aircraft to be manufactured in the private sector, making TASL the second entity after the government-owned HAL to do so. “What we are going to do for C295 is quite deep,” Singh says. “We would get aluminium, the raw material on one end, and through two factories—one in Hyderabad and one in Vadodara—we will have the final aircraft flying out. But it's not that we make the engine or avionics. Those will be bought. But it's a very meaningful first step.”

TASL will have its final assembly line in Vadodara for the C295 aircraft with the body of the aircraft being built in Hyderabad, for which the company is building a new facility. That will be followed by assembling, calibrating and integrating the engine, landing gear and avionics.

Also read: 'Our India team is very much at the heart of our sustainability efforts': Mohamed Ali

Taking the Leap

Licenced manufacturing aside, Singh says, TASL has also been taking its own risk capital, where it is spending resources towards designing and building its own intellectual property. Although the company does hold the intellectual property for a small aircraft, which signals TASL’s intention to build its own aircraft, it may still be early days when it comes to designing and developing its own commercial aircraft, or for that matter, even a fighter one.Much of that is also because development takes a long time, and products that hit the market after many years could become redundant by the time it arrives.

“One thing we don't want to do is reinvent the wheel,” Singh says. “So, if in the aircraft business, the big OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] have taken up every little niche and developed product, and if there's a niche which they have not occupied, there's a reason they've not occupied that. I'm sure if Tatas find some niche, we could design. But we are not in a tearing hurry at the aircraft design level because there's so much of it already done there.”

Recently, Chinese state-owned company Comac, established around the same time as TASL, announced the successful completion of its maiden commercial flight to emerge as a viable alternative to Boeing and Airbus in the commercial aircraft manufacturing space. TASL, however, with all its expertise in aircraft manufacturing is clear that designing a large aircraft in India certainly requires government financial support.

Recently, Chinese state-owned company Comac, established around the same time as TASL, announced the successful completion of its maiden commercial flight to emerge as a viable alternative to Boeing and Airbus in the commercial aircraft manufacturing space. TASL, however, with all its expertise in aircraft manufacturing is clear that designing a large aircraft in India certainly requires government financial support.

“To build your aircraft, you need to design the aircraft, and that turns out to be a fairly large investment,” Singh says. “And I think there you need government help because as a private entity, to take a billion-dollar risk is a bit much.”

That means, the company is ramping up its offering in unmanned surveillance offerings and artillery guns for instance. In May, the Indian Air Force received its first indigenously designed and developed loitering munitions, manufactured by TASL. These aerial weapons are capable of operating from all kinds of terrain and high-altitude areas, and can take down targets at a range of over 50 km, without exposing any personnel. The loitering munitions developed by TASL can be controlled from a ground control station where the operator gets a real-time video.

“The company has already acquired intellectual property rights for the Grob G180 SPn corporate jet and could theoretically emulate Piaggo Hammerhead and convert the Grob G180SPn into a fairly capable MALE (Medium-Altitude Long-Endurance) or HALE (High-Altitude Long-Endurance) UAV,” says Banik of GlobalData. “Although, TASL already has Sky-I and Rakshak VTOL (Vertical take-off and landing) UAVs as part of its product portfolio, they fall into the smaller Tactical UAV segment. Developing a larger MALE or HALE UAV will be a huge leap in TASL’s capabilities.”

The ramp-up in offerings also means that the company can now look beyond just the aerostructure and engine division for exports. “We are very much looking at exporting our defence products and our combat land system products, and our unmanned systems product.”

Much of that export plan also stems from the fact that the firm has a grip over the technology and design. While that’s currently limited to artillery guns, surveillance drones, combat land platforms and loitering munitions, the Tatas aren’t one to shy away from building new capabilities, especially with over a dozen platforms being developed in house.

India is expected to spend a staggering $130 billion over the next seven years as part of its plan to modernise its military, which has long suffered for reasons ranging from poor planning, allegations of corruption and a serious mismatch between strategic objectives and purchasing technology. In the current year alone, the capital outlay for defence modernisation and infrastructure development is pegged at Rs1.63 lakh crore with indigenisation and domestic manufacturing at the heart of it.

"There is an enormous amount of opportunity to indigenise and that, in turn, will help generate employment,” Singh says. “But indigenisation must also be done in a manner that India independently can develop new platforms since that will enable long-term resilience in aerospace and defence employment in India.”

The government has been attempting to reform the defence procurement and production process, and put nearly 2,000 items, including sub-systems, components, spares and line replacement units, into a list that bans their imports. Additionally, the government is also allowing for transfer of technology between the government’s premier defence agency, DRDO, and the private sector.

“The government-owned defence lab DRDO now has a policy of transfer of technology (ToT), through which technologies of successfully tested DRDO products can be transferred to private companies for large-scale production as part of a licensing agreement,” says Banik. “Companies such as Solar Industries are already leveraging this ToT policy of the DRDO and have made itself eligible to mass produce Pinaka rocket ammunition. TASL, which is also part of the Pinaka programme, will certainly leverage these private-manufacturer-friendly policies to expand its market presence in the country and cement itself as a leading Indian defence company.”

For now, the company is banking on three tried-and-tested methods to develop new products. One obviously is to ramp up on its in-house capabilities, while the other two involve partnerships with foreign partners and the DRDO. With DRDO, the company has co-developed the ATAGS gun in addition to a combat land system, known as 8x8 WhAP. It has also helped that the company has over the past decade worked across a range of OEMs ranging from Boeing to Airbus, helping them manufacture various products.

“The team has learnt in a manner that today, if you give them any aircraft, with someone’s design, they can certainly build it to world-class perfection… the full aircraft because they have learnt by picking up different pieces.”

Still, the business remains capital intensive, especially since the investments into new platforms, and research and development in the defence sector remain expensive. “TASL's gross working capital cycle, as a percentage of the revenue, improved to 125.6 percent in FY22, owing to an improvement in realisations of contract assets, which, as a percentage of the revenue, reduced to 50 percent in FY22,” India Ratings said. “India Ratings expects further realisations in contract assets, leading to positive cash flow from operations in FY23. It estimates TASL's free cash flows to remain negative, due to the large capex of about Rs1,540 crore to be incurred in FY23-FY25 mainly towards setting up of new facilities. The capex would be majorly funded through term debt. Of its estimated capex, the company had already incurred Rs250 crore at end-September 2022.”

All that means, with its consolidations complete, capacity expansion on track and a healthy order book, TASL is well-poised to capitalise on all the strengths it has built over the past decade, even if it means heavy reliance on the parent company for funding. But, with the government’s indigenisation plan on track for defence procurement, the gamble is certain to work out. “What we want, in the future, is to aspire to do things which are unique to the world and meaningful to India,” says Singh.