- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- India's 'pharmacy of the world' moniker is under threat. Here's why

India's 'pharmacy of the world' moniker is under threat. Here's why

Despite regulatory issues and pricing pressures, can India continue being the world's generic capital?

Naini is a writer at Forbes India, who likes to dabble in storytelling across all forms of media. She writes on various topics ranging from innovation and startups to cryptocurrency and agricultureâanything and everything that makes for an interesting story. Before her stint at Forbes India, she worked for close to a year at Outlook Business. With five years of work experience, she co-produces Forbes Indiaâs video series âFrom The Fieldâ and hosts the podcast âTeenpreneursâ. She also emcees at events and moderates panel discussions from time-to-time. Naini is a part of Forbes Indiaâs digital team, also handles Forbes Indiaâs Instagram account and helps plan events. An avid learner, she has completed her PGDM in Journalism from Xavier Institute of Communication and Bachelorâs of Mass Media from Sophia College for Women in Mumbai. Be it at work or home, you will not find her working without her headphones and work playlist. She loves trekking and travelling, experimenting in the kitchen, watching films and reading.

- EXCLUSIVE: How William Lauder built Estée Lauder Companies into a global beauty giant

- India has what it takes to become a global semiconductor powerhouse: Qualcomm's Rahul Patel

- Is study abroad turning burden from boon?

- Serena Williams and The Good Glamm Group form a joint venture to launch 'Wyn Beauty' for the US market

- Celebrating self-made women: W-Power list 2024

While the volume of drug manufacturing activity in India stands out in terms of its scope and scale, the manufacturing and quality challenges encountered by the FDA’s investigators here are largely similar to those seen around the world; Image: Shutterstock

While the volume of drug manufacturing activity in India stands out in terms of its scope and scale, the manufacturing and quality challenges encountered by the FDA’s investigators here are largely similar to those seen around the world; Image: Shutterstock

I

n August 2002, Ranbaxy filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to manufacture atorvastatin, the generic version of cholesterol drug Lipitor—the world's top-selling drug, generating over US$10 billion in annual revenue. In 2011, it joined a long list of Indian generics makers who have been getting the go ahead to sell in US since the 90s. Selling generics got Indian pharma giants access to the US drug market, the world’s largest and Americans got access to affordable versions of medication. [ANDA contains data which is submitted to FDA for the review and potential approval of a generic drug product].

Related stories

At the same time, as Katherine Eban writes in her book Bottle of Lies, “the world’s greatest public health innovation also became one of its greatest swindles”. In an attempt, to formulate a generic version of Lipitor, the company was found to be using lower-quality ingredients to save money, manipulating data, and allegedly selling drugs that could potentially endanger patient safety. In 2013, Ranbaxy’s US subsidiary pleaded guilty and paid about $500 million in fines. “To minimise costs and maximise profits, companies circumvented regulations and resorted to fraud: Manipulating tests to achieve positive results and concealing or altering data to cover their tracks,” writes Eban.

Also listen: Katherine Eban: Ranbaxy and the dark side of Indian pharma

A decade later, much has changed. There has been a drop in the number of significant violations, but quality compliance and data integrity continues to be an issue.

In December 2022, after an unannounced US FDA inspection of one of Intas’ manufacturing sites in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, the company was given a list of observations on FDA Form 483—around data integrity and quality compliance. “…We found a truck full of transparent plastic bags containing shredded documents and black plastic bags mostly containing documents torn randomly into pieces by hand mixed with other scrap materials…” stated the FDA’s compliance record. In a statement sent to Forbes India, the company said: “Intas responded to the FDA within the mandated time frame, has since provided two updates and is working with external Good manufacturing practice (GMP) consultants on a baseline assessment and robust remediation plan to fully address the observations.” At the time of writing, sources state that there was another ongoing US FDA inspection at one of Intas's manufacturing plants.

A few weeks ago, Sun Pharma announced that it has hit pause on releasing US-bound drugs produced at its Mohali manufacturing operations in India, after receiving a 'Consent Decree Correspondence/Non-compliance Letter' from the US FDA—it is an agreement or settlement that resolves a dispute between FDA and a company without admission of guilt (in a criminal case) or liability (in a civil case). The regulator has “directed the company to take certain corrective actions at the Mohali facility before releasing further final product batches into the US," Sun Pharma said in an exchange filing, adding that “the company is taking required corrective steps but there will be a temporary pause in release of batches from Mohali until US FDA mandated measures are implemented.”

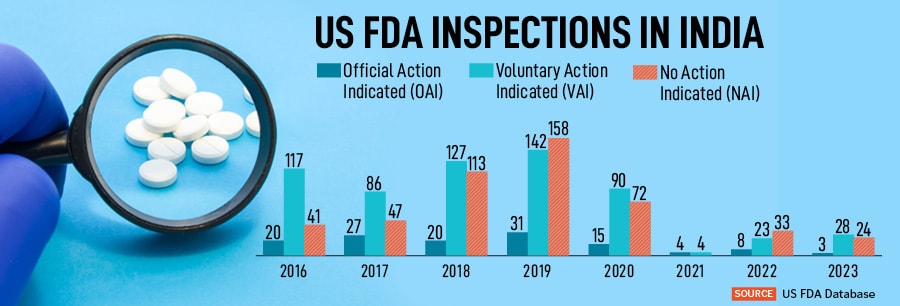

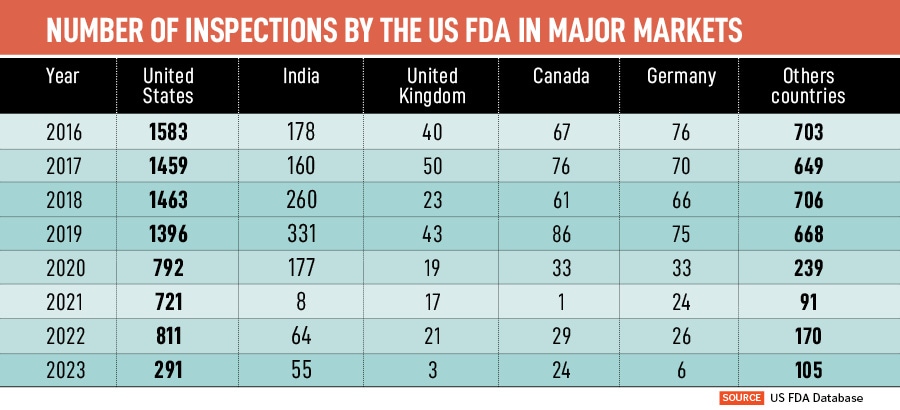

Of all the major foreign markets, India has seen the highest number of US FDA inspections—64 in 2022 and 55 in 2023 (so far). This is also because outside of the US, India has the highest number of US FDA approved manufacturing plants: 1079. While the volume of drug manufacturing activity in India stands out in terms of its scope and scale, the manufacturing and quality challenges encountered by the FDA’s investigators here are largely similar to those seen around the world. But the stakes are higher here due to the sheer scale, and India's title of ‘pharmacy of the world’. So what can be done to protect India's moniker?

Regulatory Challenges

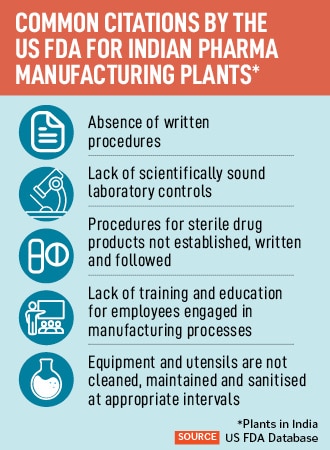

Indian pharma has often been under the regulator’s scrutiny—either there are Form 483 observations on certain facilities, warning letters issued or import alerts. The US FDA has mandatory planned inspections every couple of years as well as unannounced investigations. Recently, there have been quite a few, mostly due to the lack of inspections during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even then, why the repeated lapses in regulations?

In the US generics market, every innovator drug has a period of exclusivity. When this period is about to end, generic makers file for an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) for the review and potential approval of a generic drug product. “There is an exclusivity period of about six months—where no other company can enter the market—for the company that files the ANDA first,” explains Sanjit Singh Lamba, managing partner, Trillyum Consulting and Advisory, adding, “This is what makes companies do whatever it takes, to be first.” Often this exclusivity is shared by multiple players in the market—depending on how many file. Lately, the number for certain generics’ ANDAs have been as high as 15-20 companies.

Also read: How Indian pharma can stand up to competition with these 4 simple steps

Innovator companies take close three to four years to develop a particular formulation. “But,” explains Lamba, “there are companies who attempt to develop that same drug within 9 to 12 months.” As per Lamba, for most planned inspections, pharma companies tidy themselves up, but it is during the unannounced inspections that they may get caught. Experts reckon that failure to comply with the US FDA regulations is likely to endanger the opportunities for Indian companies in the generics market.

The US FDA over the years has constantly been raising the bar on compliance norms to improve the quality of drugs. The regulator stated in an email to Forbes India that, “The FDA is committed to collaborating closely with industry and governments to support access to safe, effective, and high-quality medications manufactured in India. We believe it is critical that India’s regulatory infrastructure keeps pace with the growth of the drug manufacturing industry in India to ensure that relevant quality and safety standards are met.”

Pharma companies reckon they are doing everything in their power to live up to the US FDA’s regulatory standards. Priyanka Chigurupati, executive director of Granules Pharmaceuticals and Granules USA says, “We are working in a Regulatory environment in which adherence to standards of quality and compliance is mandatory, the failure of which could adversely affect our business performance and loss of business. Our mitigation strategy is directed towards strengthening our capabilities by continuous learning and development initiatives on best practices and regular audits to stay in tune with ever evolving regulatory expectations.” The company is a 100 percent generics player and supplies pharmaceutical products to 300+ customers in 80+ countries—88 percent of its total revenue comes from exports, of which 50 percent is from the US market.

Maintaining good manufacturing practices (GMP), however, adds to the cost of manufacturing—both capital expenditure and operational expenditure—for a pharmaceutical company. Eban writes: "Some in the industry claim that it costs about 25 percent more to follow good manufacturing practices required for regulated markets like the United States...How can you maintain quality when a brand-name pill that costs $14 one day is going to cost 4 cents as a generic the next day?”

“Costs are increasing, but prices are dropping due to increased competition and growing bargaining power of buyers. In an attempt to cope with the drop in value, companies have been trying to increase the volume of products, which makes managing regulatory compliance even tougher,” says Vishal Manchanda, senior vice president - Institutional Research, Systematix Group.

Sources suggest that the increasing regulatory scrutiny could have something to do with the US Big Pharma lobbying against Indian generic manufacturers. Additionally, there is the “Failure to Supply” clause, “which means that if a company has committed a certain volume, and fail to supply the same they will be charged a large penalty—usually 2x or 3x of the committed volume. It often becomes challenging for companies to manage compliance under such immense pressures. Companies fill their capacities to the best utilization levels which leave little or no flexibility in managing production schedules to deal with compliance or quality problems that need detailed investigations,” Manchanda says.

Growing Pricing Pressures

Regulatory scrutiny is only one part of the problem.More recently, pharma giants are facing a massive pricing pressure in the United States, leading to reduced profitability. Reason? “The pricing pressure is the result of customer consolidation, increased competition, and recent measures by the US government to lower drug prices for customers. We believe that the resulting price erosion will lead to consolidation towards the stronger generic players,” says Chigurupati.

There are three main wholesalers, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson Corporation that account for more than 90 percent of wholesale drug distribution in the United States. With multiple suppliers, wholesalers end up having a lot of bargaining power. “Additionally, there are always new suppliers entering the market, who are willing to drop prices further to enter the market. So wholesalers negotiate with the existing players to offer the same price, for them to retain their existing market share—hence constantly hitting the prices,” says Manchanda. This leads to almost 90 percent price erosion, from the price at which the innovator sold the drug versus the generic drug prices.

There are three main wholesalers, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson Corporation that account for more than 90 percent of wholesale drug distribution in the United States. With multiple suppliers, wholesalers end up having a lot of bargaining power. “Additionally, there are always new suppliers entering the market, who are willing to drop prices further to enter the market. So wholesalers negotiate with the existing players to offer the same price, for them to retain their existing market share—hence constantly hitting the prices,” says Manchanda. This leads to almost 90 percent price erosion, from the price at which the innovator sold the drug versus the generic drug prices.

“It’s not just the wholesalers or the price wars, but also pressure from the US government to lower drug prices, making health care a lot more affordable for American people,” says Shyam Bishen, head, Centre for Health and Healthcare and member of executive committee, World Economic Forum. The US government is currently highly reliant on India for generics, and as per experts, is looking to reduce their dependency on India, but promoting pharma companies from emerging markets, too.

Channel consolidation in the US has led to the sharp headwinds for this industry, causing the market to erode by about 10 percent over five years. “Similarly, a patriotic fervour in several geographies is causing the industry to refresh their strategic priorities…Further, inflation in the recent times has caused imbalances in the cost structure which the industry is finding difficult to pass onto channel partners,” says Ramesh Swaminathan, executive director, global CFO and head of corporate affairs, Lupin. To deal with this increasing pricing pressures, the company is trying to improve operational efficiency and reduce costs throughout the value chain. “This includes optimising supply chain management, streamlining manufacturing processes, and reducing administrative expenses,” adds Swaminathan.

As prices are dropping, costs are only increasing. According to sources, it costs almost $5 million to formulate one generic drug, before filing for the ANDA. Apart from the five-year exclusivity that the innovator-led company gets, they also have multiple patents that have been filed per innovator drug. The only way to get past those patents is a litigation battle, meaning a large chunk of the huge sum also includes these litigation fees, for the generic company. Once they settle, the generic maker sets up a facility that the US FDA comes to inspect. It is only post clearance the manufacturing begins.

High Reliance on API Imports

While prices are dropping, cost of manufacturing is on the rise.

Raw material imports is a massive challenge for Indian pharma. “Chinese manufacturers continue to own the most key starting materials and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) production—which is the main ingredient for drug making—which forces Indian pharma to depend on them heavily for raw materials,” adds Bishen. According to news reports, nearly 70 per cent of the country’s APIs are imported from China; this dependence is around 90 per cent for certain life-saving antibiotics such as cephalosporins, azithromycin and penicillin.

As per data from the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilisers, the import of bulk drugs or APIs and drug intermediates from China rose 20 per cent from FY21 to Rs 23,273 crore in FY22, which was 66 percent of India’s total imports of medical products. Says Bishen, “The country needs to figure out a way to bring back manufacturing of key APIs and bulk drug intermediates to India. Some companies have already started doing this, but this would need strong government support.” In an attempt to reduce dependency on China, a lot of large pharma players are acquiring API players in India or setting up their own API production units. This allows cost of manufacturing per generic pill to drop significantly, hence increasing volumes. The government is also pushing for the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for promotion of domestic manufacturing of critical Key Starting Materials (KSMs)/ Drug Intermediates (DIs) and APIs in India.

As per data from the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilisers, the import of bulk drugs or APIs and drug intermediates from China rose 20 per cent from FY21 to Rs 23,273 crore in FY22, which was 66 percent of India’s total imports of medical products. Says Bishen, “The country needs to figure out a way to bring back manufacturing of key APIs and bulk drug intermediates to India. Some companies have already started doing this, but this would need strong government support.” In an attempt to reduce dependency on China, a lot of large pharma players are acquiring API players in India or setting up their own API production units. This allows cost of manufacturing per generic pill to drop significantly, hence increasing volumes. The government is also pushing for the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for promotion of domestic manufacturing of critical Key Starting Materials (KSMs)/ Drug Intermediates (DIs) and APIs in India.

Also read: How blockchain can help fight counterfeit drugs in India

Cost of manufacturing has been increasing and prices are dropping, which means value per generic drug is low. In an attempt to compensate for this, drug makers are trying to increase volume—either formulating various forms of the same drug or increasing the number of generics sold. This in turn, leads to a lot more quality compliance measures. “It is a vicious cycle. The generics drug industry is a volume game, not a value game,” says Manchanda.

Hedging its Bets

Experts reckon that the US generics market has delivered a muted growth in the last couple of years. “Off-late large generic manufacturers in India reported sizeable impairment losses and discontinued certain products or segments due to lower earning potential leading to muted revenue growth,” adds Roma Garg, managing consultant at data analytics and consulting company GlobalData.

In an attempt to find a way around this, many companies are now moving in the space of specialty generics to decrease their dependence on generics—which means there are fewer chances of price erosion. Sun Pharma—one of the largest generics players—has built now built an innovation-led global speciality business as an additional engine of growth. The speciality generics business accounts for 13-15 percent of its revenue.

“We are currently marketing 26 specialty products across markets, including the US, Europe, Japan, Australia, Israel and India. In FY22, our global specialty sales grew by 39 percent to reach US$ 674 million. Our global specialty sales in the first 9 months of this fiscal were US$ 627 million,” a Sun Pharma spokesperson said. The company is investing to scale up this business, especially in our core therapy areas of dermatology, ophthalmology and onco-derm.

Similarly, Lupin has a portfolio of over 200 products, including several complex generics and niche products. “The focus in the US is however pivoting to more complex therapies like inhalers, complex injectables and biosimilars,” says Swaminathan. These drugs typically face less competition, allowing companies to maintain higher prices and margins. “Additionally, Lupin has been expanding its pipeline of specialty products, including biosimilars and inhalation products, which have higher barriers to entry and lower competition,” he adds.

Granules is also expanding by venturing into new businesses beyond oral solid dosage forms, so far their growth in the US has been in prescription drugs and OTC segment. “We are moving from offering API to pure play formulations and making our presence felt and move up the value chain,” adds Chigurupati.

Indian pharma is also trying to hedge its bets by looking at geographies outside the US. “To repair these losses [in the US] Indian pharmaceutical generic manufacturer are trying to diversify their focus more on emerging markets such as Russia, other developing EU countries etc,” explains Garg.

Also read: Fighting Superbugs: How an Indian Avenger is building a life-saving weapon

While companies are looking at emerging markets, the US generics market touched US$ 86.9 billion in 2022, as per IMARC Group, hence it cannot be avoided. “Companies have been consistently trying to reduce dependence in the US. But it's very difficult, because about 30-40 percent of their revenue comes from the US,” says Manchanda. For large companies such as Lupin, the US market continues to be the largest revenue generator for the company, accounting for approximately 36 percent of its total revenues as per Q3 FY2023 financials.

Pharma players are also looking at ways to improve digital adoption for sales and marketing and optimising research and development spends through technology advancement, such as leveraging AI-enabled drug discovery to help with faster market entry. Additionally, reckons Garg, “Certain Indian pharma companies have taken initiative to invest in health care adjacencies, like Lupin and Torrent Pharma invested in diagnostics while Zydus started acquisition of multi-specialty hospital. This could help to cater underserved tier II and III cities in India,” he says.

Though generics manufacturing is far more expensive, and far less profitable, the volumes, particularly from the US markets, are allowing pharma giants to make a large chunk of their revenue from generics. But, will this continue? In the near future, probably. Adds Manchanda: “Generics as a segment has a cap to how much it can grow, eventually every pharma company will need to get into innovation to grow beyond a point.”