India's trillion-dollar opportunity

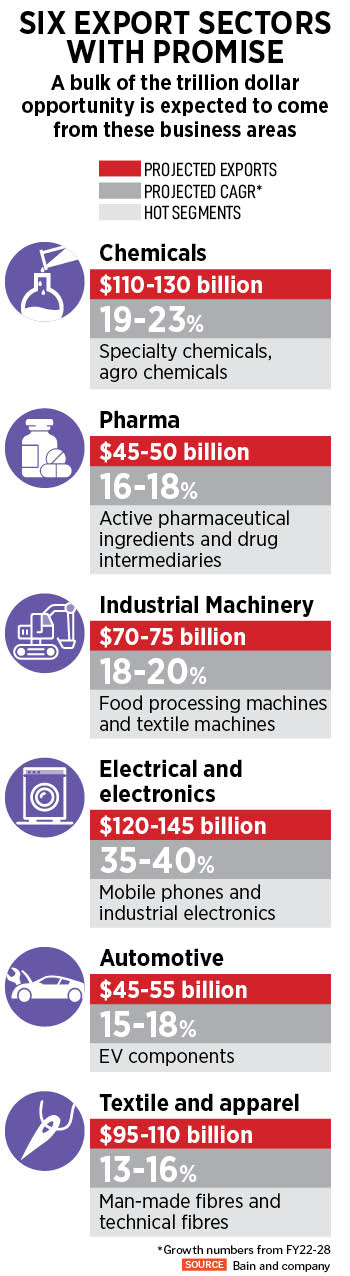

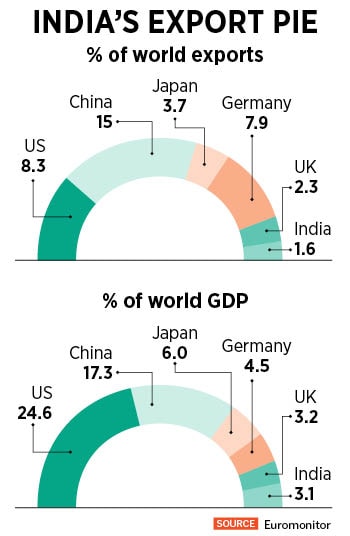

India has set itself out to be a manufacturing exporting powerhouse and with a reorientation in exports, over the next few years a bulk of the growth in export numbers could come from sectors like electronics, chemicals, and pharma

According to Dasgupta, this shift in the reorientation of Indian exports is crucial to us getting to a trillion dollars.

Image: Shutterstock

According to Dasgupta, this shift in the reorientation of Indian exports is crucial to us getting to a trillion dollars.

Image: Shutterstock

At an ABB India factory in Faridabad employees regularly walk over to take a look at a low voltage motor kept on the shop floor. The unit of the Swedish-Swiss multinational makes motors for exports and its employees have been tasked with making sure they get the quality and specifications right. It’s a test they’ve passed and the product, which is now 100 percent localised, is sent to ABB customers across the globe.

And it’s not just motors. Take for instance its factory that makes relays in Vadodara. A large part of that production is dedicated to exports. Or its recent expansion in Nashik announced in February. Expect products from there to be exported too. While ABB India doesn’t break out export numbers for specific products it’s fair to say that 12-15 percent of its Rs8500 crore turnover comprises of exports. It’s an area the company expects to focus on in the years ahead.

According to Dasgupta, this shift in the reorientation of Indian exports is crucial to us getting to a trillion dollars. It is also significant as it would help us to move up the value chain and leave our export numbers less exposed to the vagaries of commodity prices. (The increase in exports last fiscal from $422 billion to $445 billion was almost entirely on account of the rise in prices of petroleum products. Services exports were $322 billion in FY23).

According to Dasgupta, this shift in the reorientation of Indian exports is crucial to us getting to a trillion dollars. It is also significant as it would help us to move up the value chain and leave our export numbers less exposed to the vagaries of commodity prices. (The increase in exports last fiscal from $422 billion to $445 billion was almost entirely on account of the rise in prices of petroleum products. Services exports were $322 billion in FY23).  The government has decided to adopt a two-fold approach in getting businesses to set up export facing operations. The first and most publicised is the production linked incentive scheme that gives a rebate of 4-6 percent on incremental sales when compared to the first year of production. This means that businesses in effect can save up to 5 percent of the cost of production. The incentives have a five-year sunset clause.

The government has decided to adopt a two-fold approach in getting businesses to set up export facing operations. The first and most publicised is the production linked incentive scheme that gives a rebate of 4-6 percent on incremental sales when compared to the first year of production. This means that businesses in effect can save up to 5 percent of the cost of production. The incentives have a five-year sunset clause.  While a bulk of the sectors where approvals have come in are yet to start exporting, capital investment plans have been announced and the advantage of incremental exports should start accruing from FY24. Mobile phones is one area where the numbers have already started to show an uptick.

While a bulk of the sectors where approvals have come in are yet to start exporting, capital investment plans have been announced and the advantage of incremental exports should start accruing from FY24. Mobile phones is one area where the numbers have already started to show an uptick.  Just like in the 1980s Maruti’s entry gave rise to an Indian auto component system, semi-conductor manufacturing, if it takes off, can position India as a hub for manufacturing electronics, satellites, automobiles, mobile phones, laptops and defence equipment. Dasgupta says that this would be a key monitorable as a successful semi-conductor industry would make it easier for India to reach the $1trillion export mark.

Just like in the 1980s Maruti’s entry gave rise to an Indian auto component system, semi-conductor manufacturing, if it takes off, can position India as a hub for manufacturing electronics, satellites, automobiles, mobile phones, laptops and defence equipment. Dasgupta says that this would be a key monitorable as a successful semi-conductor industry would make it easier for India to reach the $1trillion export mark.