International Youth Day: The next 100 years of the planet are uncertain. The fight for the future is on

Through online activism and legal means, youngsters are fighting climate change, raising awareness and leading scientific research. Their leadership, individually and collectively has forced the establishment to acknowledge the threat to our planet and environment

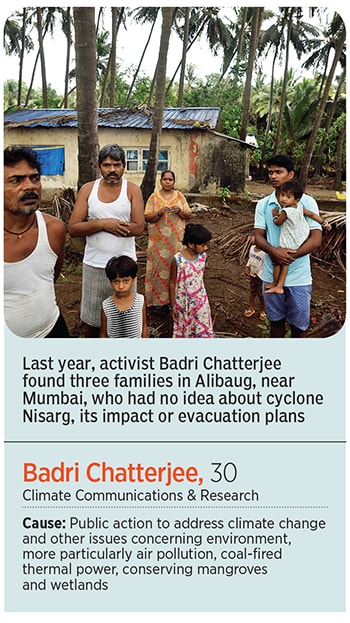

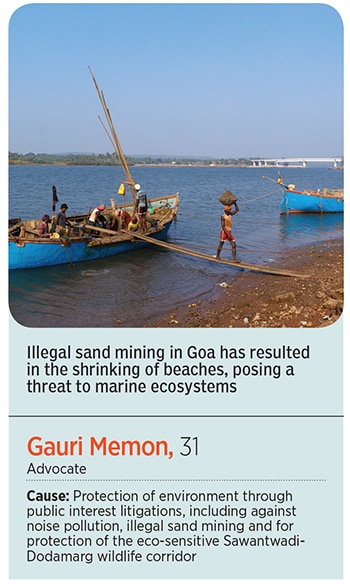

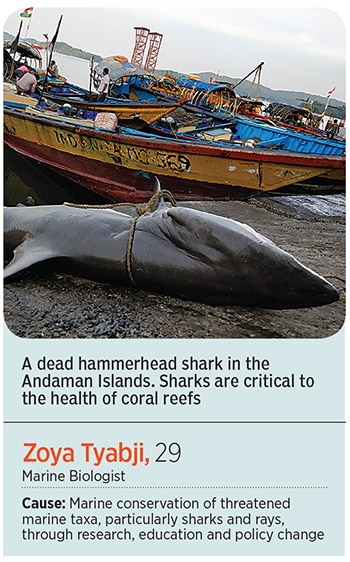

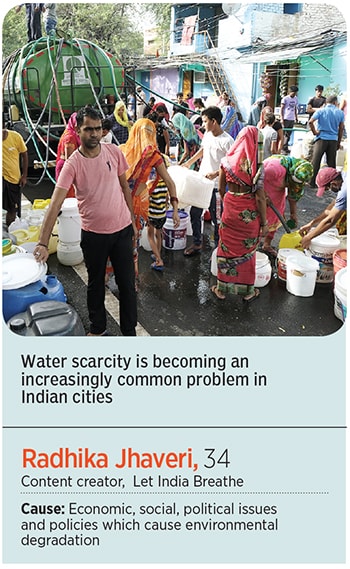

(Clockwise from right) Shanay Shah, Gauri Memon, Radhika Jhaveri, Yash Marwah, Zoya Tyabji, Badri Chatterjee

(Clockwise from right) Shanay Shah, Gauri Memon, Radhika Jhaveri, Yash Marwah, Zoya Tyabji, Badri Chatterjee

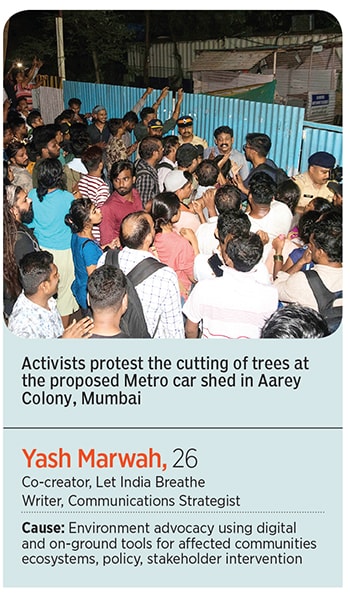

Once upon a time, a mink coat signalled success, the zenith of aspirational glamour. But mink coats aren’t cool anymore. They represent cruelty, tortured animals and violent death. “Is your diamond jewellery worth cutting 2.15 lakh trees?” asks an Instagram post from youth-led group Let India Breathe. Their opposition to open-cast diamond mining in the old-growth Buxwaha Forest, Madhya Pradesh, rejects traditional status symbols, and favours protecting forests and human rights of marginalised communities. The number of passionate young people who have fresh takes on traditional growth paradigms, and who prioritise the environment, is blossoming rapidly. Amidst devastating climate events, young people are a beacon in this changing world. They know they face a bleak future unless they step up to lead us out of our climate change woes, and they light our way forward as they channel their anguish to resistance against human behaviour that destroys climate. Their voices cannot be ignored.

“To me, there is no comparison between the value of a forest and the perceived value of diamond jewellery,” says youth leader Radhika Jhaveri poignantly. She grew up in a society where diamonds symbolised wealth, status and success. However, in her early 20s, she learnt that humans die and the environment suffers for diamond mining. Radhika decided then that she would not buy or wear any jewellery at all. “One [the environment] sustains life and the other [diamonds] brings about nothing but destruction. It’s a cost I am not willing to pay,” she says.

Diamonds are not the only reason for destroying biodiverse forests.

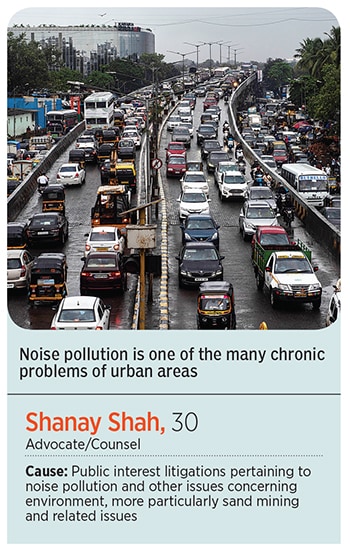

Our irreplaceable forests are destroyed daily for development projects like roads and infrastructure building, coal and mineral mining. Sand mining ravages rivers and coasts across India. Even our seas are polluted and over-fished. What we call ‘development’ has caused historically unprecedented climate change. This explosion in man-made infrastructure and waste, without environmental precaution, is making our world unliveable for our descendants.