Knocking at the door of stagflation or merely a few quarters of rising inflation?

Every household in India has been paying more for groceries over the last year. In May, India's retail inflation rose sharply to 6.3 percent on a year-on-year basis and breached RBI's 4 percent threshold

A labourer carries a sack of Beetroot at a wholesale vegetable market in New Delhi on May 17, 2021 amid a raging second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A labourer carries a sack of Beetroot at a wholesale vegetable market in New Delhi on May 17, 2021 amid a raging second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Image: Arun Sankar / AFP

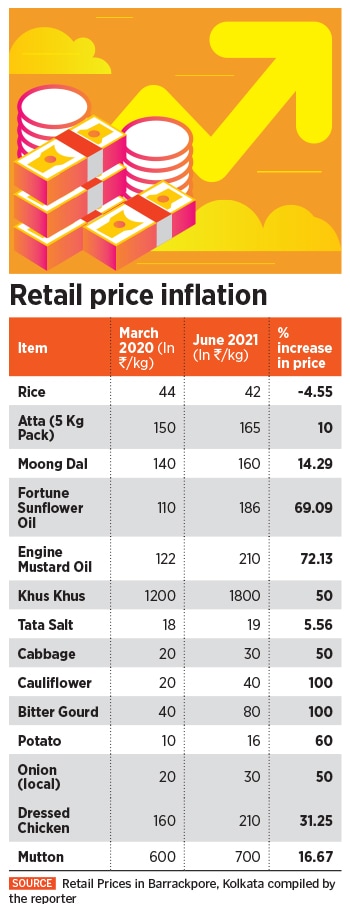

Karela (bitter gourd) rarely makes it to anyone’s vegetable list as a favourite, but if it did then you would have noticed that last year one paid Rs 40 per kg for bitter gourd in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata, while a year later it costs Rs 80 per kg in the retail market, a sharp rise of 100 percent.

It’s not just bitter gourd. Vegetables as basic as potatoes and onions have seen their prices go up by 50-60 percent over the last one year in Kolkata.

If you are someone who keeps a tab on expenses, then you would have noticed by now that prices of groceries, vegetables and poultry have only inched upwards since last year. For example, a packet of edible sunflower oil which was priced at about Rs 110 per litre now costs nearly Rs 186 per litre, an increase of 69 percent on a year-on-year basis. Blame it on imports or supply side pressures in terms of production and logistics issues, this has led to food inflation. Simply put, an increase in prices. (Please refer to the chart below for more items)

“We are moving to a higher inflation trajectory and it is best to learn to live with this,” says Abheek Barua, chief economist at HDFC Bank.

What this essentially means is that every household in India has been paying more for groceries over the last year. In May, India’s retail inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose sharply to 6.3 percent on a year-on-year basis, breaching the RBI’s inflation target of 4 percent again (with an upper margin to go up to 6 percent) after a gap of five months. The central bank has kept its rate unchanged at a record low level of 4 percent and expects rural demand to remain strong owing to a good monsoon.

Barua says, “We expect the next year to have elevated inflation with low growth. Growth doesn’t look like it will fall below 8.5-9 percent even in the worst case scenario--as exports and public investments should pick up the slack."

Barua says, “We expect the next year to have elevated inflation with low growth. Growth doesn’t look like it will fall below 8.5-9 percent even in the worst case scenario--as exports and public investments should pick up the slack."