- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Lesson Plan: Inside LEAD School's strategy for quality education in small-town India

Lesson Plan: Inside LEAD School's strategy for quality education in small-town India

Prioritising an outcomes-led pedagogy, supported by tech and data, LEAD's founders want to overhaul school education in the country, from within

I'm the Technology Editor at Forbes India and I love writing about all things tech. Explaining the big picture, where tech meets business and society, is what drives me. I don't get to do that every day, but I live for those well-crafted stories, written simply, sans jargon.

- Zoho: Busting the myth that great software can only be written in Silicon Valley

- Ashok Leyland: From tradition to transition

- Solving for India: Five startups tackling social problems

- How Larsen & Toubro Infotech came into its own

- Dhruvil Sanghvi is working to make LogiNext the Google of supply-chain logistics

Sumeet Mehta and Smita Deorah, cofounders, LEAD School

Sumeet Mehta and Smita Deorah, cofounders, LEAD School

Sumeet Mehta’s dinner-time conversations with his parents and siblings often revolved around education, with his English professor father quoting Shakespeare, Shelley, or Keats.

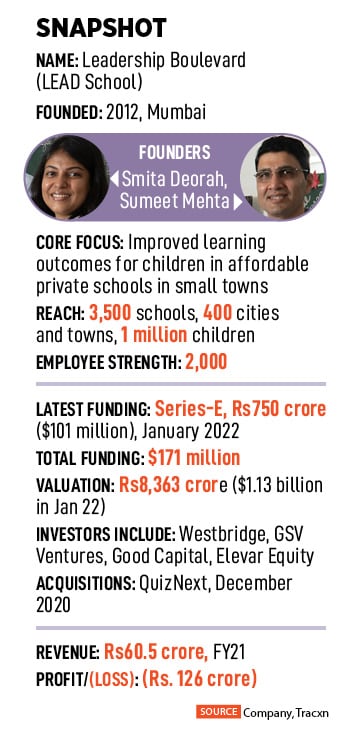

That influence later played a part in him joining Smita Deorah, his life partner, to start their edtech venture Leadership Boulevard, better known as LEAD School, in Mumbai.

Related stories

It was 2010. The duo had been back in India for about three years, from Singapore. “Both our children were born in India,” Deorah says. Curiosity took her on a visit one day to the home of her domestic help, and she saw first-hand the lack of access to good schools and teachers for lower income families, and how their children struggled with even the basics.

“I was just heartbroken,” Deorah recalls. She’d been experimenting with her own first-born, her daughter, with the latest research findings on how children learn – something that she and Mehta were doing a deep dive into – and “by the age of three, no one needed to read to her anymore,” she recalls.

“If my kids could do well, so could others,” she says, with the right kind of intervention. That was the germ of the idea that would eventually become LEAD. The name is also an acronym – Leadership in Education and Development.

The journey started with Sparsh, a non-profit organisation that Deorah started, developing a school-in-a-box solution for pre-schools. She worked with some 16 anganwadis, with about half of those in partnership with government agencies.

The learnings convinced her she needed to switch to a private, for-profit venture, where she could move fast. Thus, was born LEAD and “I convinced Sumeet to join me,” she says. It was now late 2012.

The duo started with setting up their own private affordable school in a village in Gujarat. Then four more in Maharashtra, again in small towns. Their interventions yielded measurable improvements in the learning outcomes of children across the five schools, Deorah says.

So went about five years, and they were ready for scale and therefore switch to partnering existing schools, instead of setting up their own.

The business model transitioned into partnering schools, allowing LEAD to focus on what the founders were passionate about—researching, designing, and planning the delivery of high-quality education. The schools themselves would execute according to LEAD’s design and plans.

Also read: Deconstructing ancient worlds to build our own: The case of education

The LEAD System

By 2016-17, LEAD, as it has evolved into today, was beginning to emerge. Today, the company partners about 3,500 affordable private schools in some 400 cities across the country, touching a million students. These schools use the LEAD System. And serving them are LEAD’s close to 2,000 employees.This system has two important components. First, a curriculum that is contextualised for the students and teachers. Second, it is integrated with technology to move the teaching away from a linear grading-oriented exercise to a comprehensive learning-oriented effort.

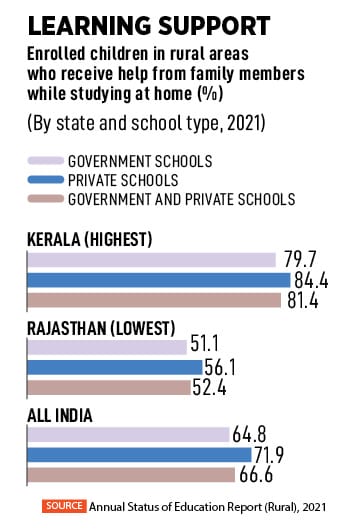

The contextualisation is about specifically addressing the gap that students have between what’s expected at a particular grade and their current capabilities. For example, this can be because their English is poor, and most subjects are taught in English. LEAD’s system attacks these kinds of root causes of the gap, Deorah says.

Therefore, a curriculum taught in a “high-fee” school in a metro won’t work in the type of school that LEAD partners. It will have to be designed differently, with a lot more visuals, for example, or be much more activity-oriented.

For example, in the case of English itself, LEAD offers a programme called ELGA (English Language and General Awareness). It isn’t based on grades, but on skill levels. Students, when they first come into a LEAD partner school, are assessed, and assigned to the right Elga class, which is often a mix of students from different grades.

Typically, in a year, Elga helps the children acquire skills beyond that of one academic cycle. And in two to three years, they would have advanced to their grade-level English language skills. Over the last seven years, consistently, LEAD has delivered 1.5-1.6 years of average skill development in a one-year academic cycle, and with low-skill teachers, Deorah says.

And this is important, says CMO Anupam Gurani, because the schools that LEAD works with are in Tier-III, Tier-IV cities and towns, and these teachers are underpaid and under-skilled as well, even if they are highly motivated.

“Student outcomes are our North Star metric,” Deorah says, “with 1.5 years of English language skill growth and 70 percent-plus mastery across all grades across all subjects.”

The LEAD product includes innovations in pedagogy that “any graduate can pick up and become a good teacher,” Deorah says. She likes to describe this as “microwave-ready lesson plans” that teachers can use to just focus on delivery in the classroom.

At the school level, LEAD is bringing about habit changes, including going into minute details of the daily timetable and which students will go where. And data-driven decisions are integral to everything that teachers do. For example, in determining remedial classroom action with a student who might have fallen behind. Overall, “if you walk into a LEAD partner school, you’ll see it operating very differently from any small-town school that we are used to,” she says.

One critical aspect of LEAD’s work is that it operates within the school system itself, rather than sell courses or classes outside the school.

This probably helps parents save money outside on private tuitions, given that they are already in a price-sensitive market segment. And when the parents see their children doing better in the schools, that feeds back into strengthening LEAD’s partnerships with the schools, which is vital to its long-term commercial success.

Also read: Meet the players blossoming despite the edtech winter

Low-cost Tech, High Impact

The hardware part of the tech is relatively low-cost, comprising a television in the class and a tablet in the hands of the teacher. The software, is a continually improving platform.

Today, LEAD has clear product-market-fit, says Ajay Kashyap, head of product. The teacher uses an app on the tablet to access a step-by-step lesson plan that she uses throughout the typical 40-minute class. And tied to it very closely are other physical teaching aids and the textbooks supplied by LEAD, which also provides and installs the hardware.

With the TV in the class and a tablet in the hands of the teacher, “the teacher’s back isn’t facing the students anymore,” Mehta says, unlike the traditional method that involves writing on the blackboard and getting the students to learn by rote.

With the TV in the class and a tablet in the hands of the teacher, “the teacher’s back isn’t facing the students anymore,” Mehta says, unlike the traditional method that involves writing on the blackboard and getting the students to learn by rote.

This system works in areas with sketchy internet connections as well. And this approach involves a tight integration of the textbooks and the multimedia content. Elsewhere, “smart classes” are about screening some videos a couple of times a week, Deorah says, where the teacher can offer little connection between what’s in a video and what’s being taught.

LEAD’s innovations are not necessarily fancy, but in the service of improved learning outcomes for students. For example, with some tests, optical character recognition is used to “auto populate” marks, freeing up the teacher a bit. Similarly, recommendations of remedial actions based on performance data of each student are automated, Kashyap says.

Or with the school ERP software, the aim is that it should become increasingly invisible, he says, meaning it should “just work.”

Granular data is available at different levels, from individual students and the teacher in a class to the principal and the school management. Parents get to know what’s really happening with their children, and school owners get data and information on what’s working in their schools and what needs work, which helps them boost admissions.

When Covid hit, LEAD also developed an app for parents on their mobile phones and now data from that app is also feeding into its systems.

Two years ago, there were well-articulated lesson plans and multimedia information. Today, “what we’ve been able to differentiate with, is that the quality of what the student does at home is much more comprehensive,” says Harsh Kundra, chief technology officer, LEAD.

The product has moved from a basic version to one that offers many more features, including activities and quizzes that connect closely with what’s happening in the school. There are also more resources that are interactive.

Also read: The constantly evolving educators of edtech

Turning Unicorn

The business model involves the schools paying a per-student fee to LEAD, typically on three-year contracts. In addition to the core promise of delivering students’ learning outcomes, LEAD has also started helping the schools with their business growth, Deorah says, by connecting parents with the nearest LEAD partner school, for example, which boosts admissions.LEAD did about Rs60 crore in revenue for the fiscal year 2020-21, and more than doubled it for FY 2021-22, Deorah says, while an exact figure couldn’t be revealed because the company was about to file its numbers with the ministry of corporate affairs. Losses for 2020-21 were at Rs126 crore, according to data from private markets intelligence provider Tracxn.

“This year (FY 2022-23), we will end with 2X revenue growth, and we are on track to do another 2X next year,” adds Gurani, who is also responsible for the chief revenue officer’s function. “And by the end of next year, we should be looking at profitability.”

“The good thing with our business is that because we work on academic cycles, we sign our schools and have contracts signed a year in advance, so we have visibility into our order book and our portfolio,” Deorah says.

In 2017, Deorah and Mehta raised Rs10 crore in Series-A funding in a round led by Elevar Equity, a venture capital firm in Bengaluru. This was also around the time when LEAD’s partnership model was beginning. Adding schools quickly, LEAD went from Series-A to Series-E, with other marquee investors backing them, notably Westbridge Capital and GSV Ventures.

“We could see that they knew what they were doing,” says Sandeep Farias, founder and managing partner at Elevar, recalling the first investment his firm made in LEAD. “They had (already) spent five years actually delivering learning outcomes in remote areas across schools that were completely run by them.” This combination of LEAD’s focus on learning outcomes, when combined with the founders’ execution experience, was compelling, Farias says.

“If you choose your stakeholders carefully, including the investors, because they are going to be with you on this journey for a while, if you do it thoughtfully, you will not—as an entrepreneur, as a founder—get pulled in different directions,” Deorah reflects.

“Lakshmi will follow Saraswati,” she says, referring to the Hindu goddesses of prosperity and learning respectively. Meaning, deliver the educational outcomes and the money will follow.

The Rs750 crore Series-E round, in January this year, saw the company being valued at Rs8,363 crore ($1.1 billion at the time), according to Tracxn.

Also read: Can vernacular edtech become mainstream?

Early Influence

To understand this passion for education, let’s go back to where we started. “My dad was this maverick teacher, who just loved his job,” Mehta recalls.Sometimes, his father would hold up a roti, cut it in different pieces and say, “you’ve done fractions today at school, which fraction is this piece,” and Mehta – the youngest of three siblings – and his brother and sister were expected to answer.

This gamified learning over the dinner table was extended to other subjects too and transferred to the terrace of their house on summer evenings.

An assignment, one day, when Mehta was a third grader or thereabouts, was to write something about a local railway station. And to his utter delight, “which 40 years on, I still remember,” he says, his father picked his copy as the best one, versus his brother’s, who is about three years older or his sister, the eldest by eight years.

An assignment, one day, when Mehta was a third grader or thereabouts, was to write something about a local railway station. And to his utter delight, “which 40 years on, I still remember,” he says, his father picked his copy as the best one, versus his brother’s, who is about three years older or his sister, the eldest by eight years.

Another activity was to open out an atlas, and whoever located a place called out by his dad was the winner.

Later, as an older boy, he noticed that wherever they went—Mehta grew up in around the towns of Pathankot and Gurdaspur in Punjab—someone would come up and say ‘aap ne mujhe padhaaya tha’ (you were my teacher), and occasionally, someone would remember this from 20 years ago, for example.

Looking at today’s children struggling with various subjects, which his father had made it easy for him to learn, Mehta says “the massive impact that a great teacher can have stayed with me.”

For Deorah, it was the DNA of grit and hard work that she and her sibling, an IIT Bombay graduate, inherited from her parents. College didn’t hold much attraction for her, and she was already working in parallel, preparing to become a chartered accountant, convinced by her father that it was a better track for her than engineering.

The CA’s qualification started her out with a PwC internship and the desire to apply her learning took her to Procter & Gamble, where she met Mehta. After several years at the FMCG giant, they came back from Singapore.

The entrepreneurial journey at LEAD has tested her grit, she admits. It has also boosted her solution orientation manifold over the last decade. She refuses to get into any negative space, she says, and always looks for opportunity in every challenge.

For example, when Covid hit, there were three weeks of school still left, before the students would take a break for exams, she recalls. In Bengaluru, for example, the government announced schools were shutting on March 11, 2020, and LEAD launched its LEAD School at Home solution in a matter of five days, by March 16, initially starting with YouTube, and then bringing it on to the LEAD platform.

Ambition: 25 Million Children

“Everything that people can do, or are not able to do, connects back to their education,” Mehta says. The big opportunity for LEAD is that every child goes to school and spends six-seven hours every day, but the quality of those hours isn’t good.“If we can transform these schools, we will have a material impact on the nation’s economy. This scale is the biggest opportunity,” he says. Do this, and all the metrics, from children’s learning to the country’s economy, will take care of themselves, he says.

Today, LEAD caters to affordable private schools—typically, with fees in the range of Rs. 12,000-30,000 per year—and within that its penetration is at 1.5-2 percent, Mehta says. Over the next five years, the aim is to hit at least 15 percent penetration.

There are segments that LEAD in which doesn’t yet operate. For example, low-fee schools, that charge Rs10,000 or less per year, which also tend to be vernacular or bilingual. A version of LEAD’s product could work for these schools and make meaningful impact, Mehta says.

Classes 11 and 12 are another opportunity as LEAD currently stops at class 10. In the “high-fee” schools where basic education is largely well taken care of, there are opportunities in teaching life skills and offering a more holistic approach.

Therefore, the aim, from a product-design perspective is to have a version of LEAD’s product available for every type of school in India. Making assessments and giving schools recommendations is also another opportunity.

With LEAD’s current business model, meeting costs via revenue and turning a profit depends on hitting a certain scale. That threshold is at about 5,000 schools Mehta says, and at 7,000 schools, LEAD will be able to make money at the level where it can invest more in future growth as well.

In the 10-year horizon, the founders would like to see LEAD as a listed company. The next five years will see them heavily focused on India. And over those five years, the ambition is to go from 3,500 schools and one million students to about 60,000 schools, touching 25 million children, Kashyap, the product chief, says.

And that will still leave massive headroom to grow. India has about 1.5 million schools, of which about a million are government schools, and about 280-290 million school-going children, Deorah says.

And, while things can go wrong in execution, perhaps the biggest challenge is not directly about adding more schools. It’s really about habit change, because that’s essentially what they are trying to achieve.

Also read: Work, Force, Energy & PhysicsWallah: Meet 'Robinhood' Pandey, and his freshly minted edtech unicorn

Category Creator

There is also the challenge of perception. LEAD isn’t the first company to make multimedia content. Educomp Solutions did this earlier, for example, CTO Kundra points out. The difference is that “we are something of a category creator” in the way LEAD is trying to tie everything together – textbooks, digital content, schoolwork, and homework. Real-time or near-real-time information on where students stand in their learning is available to both the schools and the parents.

The difference is that “we are something of a category creator” in the way LEAD is trying to tie everything together – textbooks, digital content, schoolwork, and homework. Real-time or near-real-time information on where students stand in their learning is available to both the schools and the parents.

The challenge is to not only achieve this differentiation, but also to be clearly seen as a company that is doing so, and not getting grouped with other “publishers,” in the minds of school owners, Kundra says.

The brand positioning isn’t just about communication but starts with the design of the curriculum itself from the point of view of making each child more confident, says Gurani. He recalls moving from the Gurgaon of the early 80s, with little English, to a school in Delhi for his own class 11 and being stumped by the ease with which some classmates conversed in English.

LEAD looks at schools as leaders and challengers, and the bulk of its partner schools are in the challenger category, he says. And LEAD’s promise is that it will raise a partner school to leadership position via academic success resulting in lower attrition and higher admissions and fees over a period of two-three years, leading to commercial success and greater reputation for the school in society at large.

The significance of LEAD’s work is that the entrepreneurs are trying to overhaul the “effectiveness” of the time millions of children spend in schools towards ensuring that students graduate with confidence, Farias, at Elevar, says.

“This is huge, for a socio-economic segment (parents) that deeply values the importance of quality education, having missed out on it themselves. This is transformational for children, parents and communities,” he says.

The challenge will be to sustain the momentum by not losing focus on the importance of improving learning outcomes, continuing to find the right investors, who understand that, and inspiring LEAD’s growing team to keep raising the bar.

In their marriage, their personalities have rubbed off on each other over the years, Mehta says, adding “Mere jaise ban jaoge, jab ishq tumhe ho jaayega,” (You’ll become like me, when you fall in love) quoting ghazal singers Jagjit Singh and Chitra Singh. Mehta’s intuition-led approach is now tempered by Deorah’s attention to detail and ability to anticipate problems, and vice versa, he says.

All they need to do now, together, is to rub off on another 55,000 schools or so.