Misdiagnosed: India's medical education struggles to treat its own ailments

Indian medical graduates face overwhelming challenges and dangerous working conditions. As protests erupt and calls for reform grow, can India address its medical education crisis before it's too late?

Medical students and doctors shout slogans during a protest rally against the rape and murder of a PGT woman doctor at Government-run R G Kar Medical College & Hospital in Kolkata, India, on September 7, 2024. Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Medical students and doctors shout slogans during a protest rally against the rape and murder of a PGT woman doctor at Government-run R G Kar Medical College & Hospital in Kolkata, India, on September 7, 2024. Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Vidisha Mishra, 25, and Priyansh Shah, 26, are both Indian MBBS graduates who lead two drastically different lives. Mishra is a general medicine resident at a medical college in Karnataka, while Shah is an internal medicine resident at New York's Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Mishra, locked into a relentless cycle of 36-hour to 48-hour shifts, describes being “overworked, underpaid, and trapped in a toxic work environment”. Shah, in contrast, speaks of opportunities—completing an internship at Yale, working as a research fellow at Harvard, Johns Hopkins and the World Health Organization, and founding a non-profit. Where Mishra wakes up dreading her work daily, Shah looks forward to new possibilities.

Like Mishra, Shreya Shaw, 25, another resident doctor, is anxious about her future as a doctor in India. She is a resident at RG Kar Medical College, which has been in the spotlight since August 9, when the disfigured body of a resident doctor was found in a seminar hall. The incident ignited nationwide protests over the mishandling of the rape and murder case, leading to a Supreme Court hearing.

Shaw, her fellow residents and doctors across the country are on strike, demanding the introduction of Central Protection Act and other policy frameworks to protect them. Meanwhile, a 10-member National Task Force has been established to develop protocols ensuring the safety and security of doctors, and other health care professionals. “The response has been slow,” Shaw remarks following a hearing where the Supreme Court directed the protesting doctors to resume work by September 10. “No concrete action has been taken yet. Who’s to say it won’t happen again?” she asks, frustration evident in her voice as she expands on the lack of security for residents and doctors in hospitals across the country.

This incident barely scratches the surface of the systemic violence that doctors encounter. According to a 2019 study in The Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 75 percent of doctors report experiencing violence, and a 2024 National Medical Council survey found that almost 37,000 medical students have self-reported mental health issues with suicidal risk.

_20220316022208_102x77.jpg)

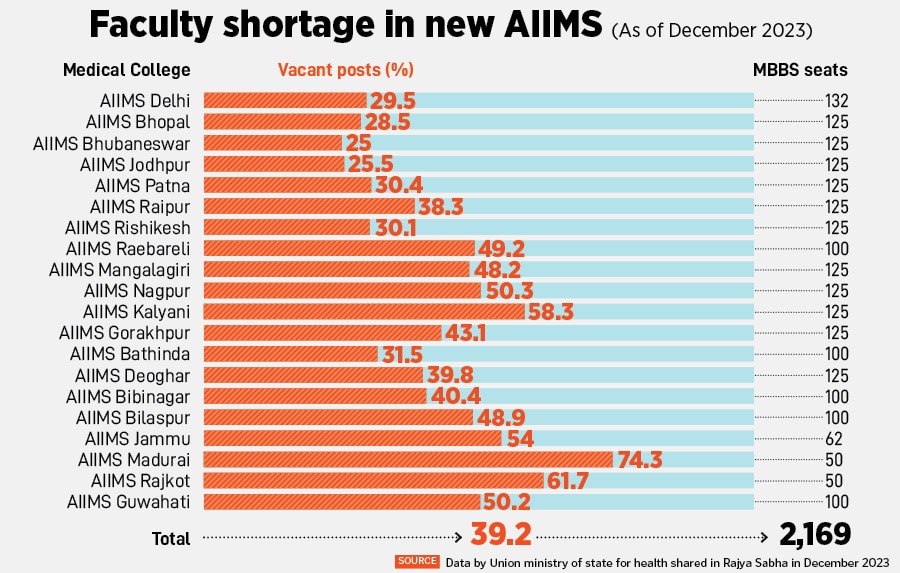

Data on PG specialists in community health centers (CHCs) shows the shortfall widening between 2005 and 2022, from 46 percent to 80 percent. This is concerning, considering that the disease burden associated with six of the top 10 causes of death in India requires the attention of specialist doctors. Select states have attempted to address this shortage by promoting alternative routes to specialisation (e.g., DNB, CPS). But a lack of uniform recognition across states and by the National Medical Commission has affected the uptake of these courses and, in turn, the availability of specialists, a CSEP report points out.

Data on PG specialists in community health centers (CHCs) shows the shortfall widening between 2005 and 2022, from 46 percent to 80 percent. This is concerning, considering that the disease burden associated with six of the top 10 causes of death in India requires the attention of specialist doctors. Select states have attempted to address this shortage by promoting alternative routes to specialisation (e.g., DNB, CPS). But a lack of uniform recognition across states and by the National Medical Commission has affected the uptake of these courses and, in turn, the availability of specialists, a CSEP report points out.