NEET Exam Row: Students in Kota helpless, frustrated, angry and confused

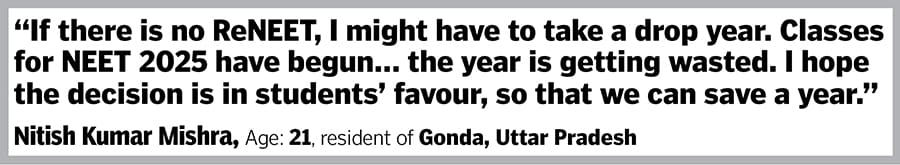

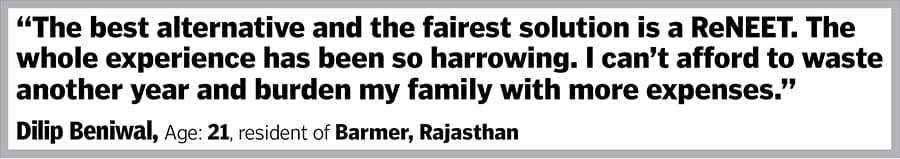

Aspirants await Supreme Court decision on ReNEET on July 8 amid controversy about paper leaks. They confess there is no motivation to pursue their dreams or the momentum to study again. And that the uncertainty and financial pressure are taking a mental toll

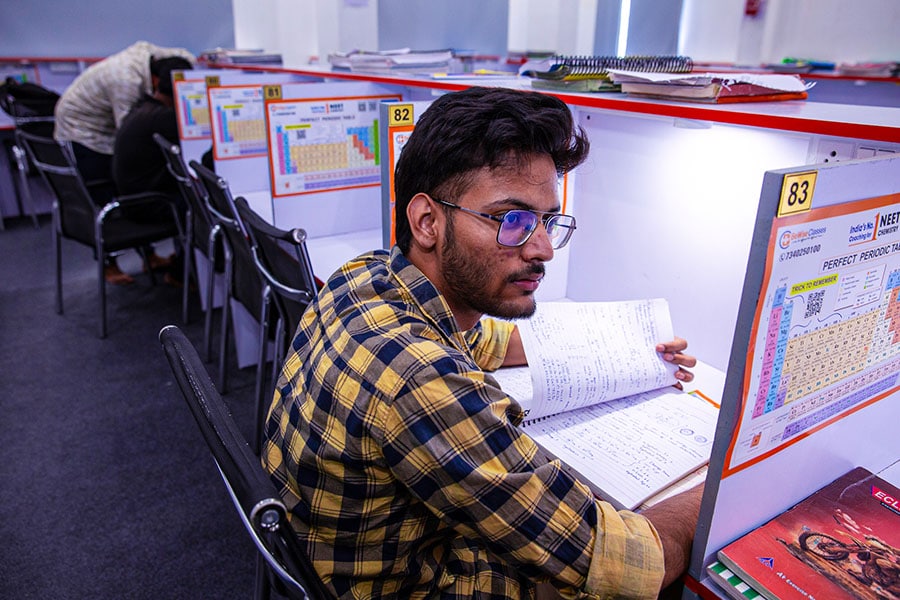

Bihar residents Lakshya Raj, Newton Kumar, and Mayank Shekhar (L-R) came to Kota with the dream of becoming doctors, but now stare at an uncertain future despite giving it their all in this year's NEET examination. Image: Madhu Kapparath

Bihar residents Lakshya Raj, Newton Kumar, and Mayank Shekhar (L-R) came to Kota with the dream of becoming doctors, but now stare at an uncertain future despite giving it their all in this year's NEET examination. Image: Madhu Kapparath

Newton Kumar and Lakshya Raj came to Kota two years ago with one aspiration and a single aim—clearing the NEET exam to become doctors. “My only dream was to become a doctor,” says Kumar, 21, a resident of Samastipur in Bihar. His friend, Raj, adds, “My dream was to become the first doctor in my district.”

However, with their current ranks against their NEET scores, they won’t be able to secure a seat in any decent medical college. “The scariest thing in the world is for dreams to die,” says Kumar, referring to the recent education scam that has left NEET aspirants like him in a state of despair.

NEET or The National Eligibility cum Entrance Test is a highly competitive exam conducted by the National Testing Agency (NTA) for admissions to courses in medical fields such as MBBS, BDS and AYUSH in government and private institutions in India. According to reports, there are about 1.09 lakh MBBS seats in more than 700 medical colleges in the country. This year, approximately 24 lakh candidates appeared for the world’s biggest medical entrance test on May 5.

However, since the results were announced on June 4, 10 days earlier than scheduled, the exam and its conducting agency have been embroiled in controversies over paper leaks, hidden grace marks, high cut-off scores, inflated ranks, and 67 students scoring full marks—a shockingly high figure in the NTA’s history. In 2022 and 2023, only two students scored 720/720, while there were three such students in 2021.

It is for these irregularities that the Supreme Court will hear a batch of pleas on July 8 from petitioners whose demand is that the exam be held again.