Climate cinema is not new in India. What would it take for it to become mainstream?

India has a rich history of environmental films, mostly fiction, that were never looked at from an ecological lens. After the 1990s, such films have been fewer, but some filmmakers are now changing that, even winning the occasional Oscar

Shaunak Sen, director of All That Breathes, which was nominated for an Oscar

Image: Amit Verma

Shaunak Sen, director of All That Breathes, which was nominated for an Oscar

Image: Amit Verma

The year is 1971, and an unlikely cinematic pair has caught the public’s fancy. Actor Rajesh Khanna and… an elephant.

Haathi Mere Saathi (and its catchy title song, ‘Chal, chal, chal, mere haathi, O mere saathi’), a story about an orphan (Khanna) and four elephants building a life and livelihood together, captured the imagination of the Indian moviegoer, making it a record-breaking hit that year. More than 50 years later, another human-elephant film from India made history, as The Elephant Whisperers (2022) won an Oscar for Best Documentary Short, a first for the country.

“When Haathi Mere Saathi was released in the 1970s, and Pather Panchali by Satyajit Ray in the 1950s, those films were not seen as ecological films,” says Pankaj Jain, professor at Flame University, Pune, teaching philosophy and religious studies. “I think that’s because ecology was never a separate category from human society, or Indian or human culture, right? Animals, trees, nature, rain were always integral part of being human.”

Today, however, that context has changed.

“Unfortunately, I think the gap has widened. Most people now live in urbanised areas across India, even if they are in small towns, or what we call tier 2 and 3 cities—or even villages,” Jain adds. “This means so many of us have lost touch with animals, birds or nature in general. It certainly seems like our filmmakers have, so we rarely see films such as Haathi Mere Saathi or Pather Panchali being made.”

In fact, a 2017 film called Kadvi Hawa, which tackles a story about drought-prone regions in India, farmer suicides and an overarching theme of climate change and its impact, has been considered a pioneering movie about the subject in India. That’s what got Jain thinking: Was it really the first such film?

The Elephant Whisperers (2022) is about a couple who cares for an orphaned elephant in South India; it won an Oscar for Best Documentary Short

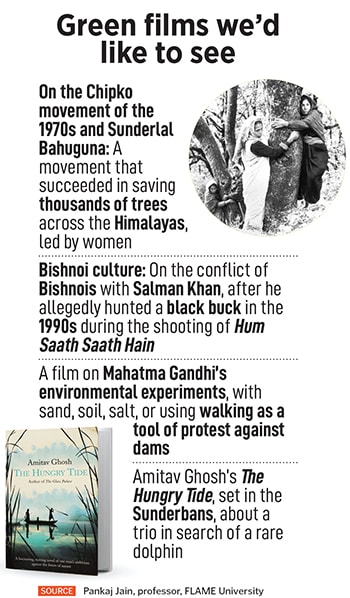

The Elephant Whisperers (2022) is about a couple who cares for an orphaned elephant in South India; it won an Oscar for Best Documentary ShortJain and his colleague Shikha Sharma set out on a research project, “to survey Indian films that have shown or dealt with nature, environment or climate, starting from the 1940s till present day”. In a paper titled Children of the Soil to Dark Wind: Nature, Environment and Climate in Indian films, published in April 2023, the authors put together a comprehensive list of films that deal with various environmental issues, by category.

The paper shows how themes of natural disasters, mostly earthquakes and floods, have been used abundantly as turning points in films (from Mother India to Kedarnath); along with famine and farming (Lagaan); fossil fuels and pollution (Ram Teri Ganga Maili, Gangs of Wasseypur); and animals and natural preservation (Kanchenjungha, Ship of Theseus).

Also read: Bhumi Pednekar: Leading by example

“Another essential feature of these Indian films, of course, is their poetic songs and ever-popular music amplifying the ecological message. These films have won numerous awards at home and abroad, yet are rarely recognised for any environmental impact,” the paper states.

With the avenues of OTT and with the growing threat of climate change, arguably, we have seen a rise in the number of environment-related films in the recent past. The most mainstream, perhaps, was The Archies, Zoya Akhtar’s debutant extravaganza, which was packaged as a bit of a popcorn flick. Set in 1960s India, the Archie-Betty-Veronica love triangle centres around the idea of a pivotal park being torn down by real estate developers, and the politics of planet-versus-profit.

“Indian cinema has dealt with ecological narratives since decades in a range of work—mainstream cinema, independent features, documentaries and series,” says Meenakshi Shedde, film journalist, curator and critic.

According to her, these include Girish Kasaravalli’s Dweepa (Island, Kannada, 2002), Nila Madhab Panda’s Kadvi Hawa (Dark Wind, 2017) and the water-shortage satire Kaun Kitney Paani Mein (starring Radhika Apte, 2015); Richie Mehta’s series Poacher (a poaching crime drama, Malayalam, 2023, starring Nimisha Sajayan and Roshan Mathew); Shaunak Sen’s Oscar-nominated All That Breathes (Best Documentary Feature, 2023), and Kartiki Gonsalves’ Oscar-winning The Elephant Whisperers (Best Documentary Short, 2023).

“The latest is a masterly film, Christo Tomy’s Ullozhukku (Undercurrent, Malayalam), starring Parvathy Thiruvothu and Urvashi,” she adds. “In most cases of fiction, while environmental issues are at the heart of the film, a skilled director is often able to use them to make metaphorical points. In Dweepa, for instance, with incessant rains and submerging of land, the displaced people are not only given very meagre compensation by the government, but they also lose their status as a respected family and become one of the millions of faceless, jobless people, their social status in tatters as well.”

In Haathi Mere Saathi (1971), an orphan builds a life with four elephants, and then has to choose between his human and animal families

In Haathi Mere Saathi (1971), an orphan builds a life with four elephants, and then has to choose between his human and animal familiesSimilarly, in Ullozhukku, she adds, Tomy uses incessant rain and floodwaters that enter the home and prevent the burial of the dead, to make a devastating comment on the state of Indian marriage—‘a rotting corpse’—but he also offers a revolutionary alternative to the traditional marriage and family.

“Sen’s All That Breathes, while showing us how kites, birds of prey, drop from Delhi’s skies because of air pollution, also comments on the connectedness of all life forms, and the horrific violence the Hindu majority wreak on Muslims with impunity,” Shedde says.

Even so, the reach for many of the recent films, especially the documentaries, has been limited. What would it take for climate issues to become mainstream films that draw in an audience?

The problem begins with access to funding.

“The truth is that there aren’t enough grants for creative Indian documentaries to work from India, so you’re thrown into the deep end and are vying for very, very competitive global grants, with films from all over the world,” says Sen, filmmaker, and director of the Oscar-nominated All That Breathes. His film was a product of multiple grants and private equity investments, and won ‘Best Documentary’ awards at Sundance and Cannes, and more recently, the prestigious Peabody Award.

“Then you try and find producers who share your vision, and basically are hurtling from one pitching forum to the other, till one can cobble together a patchwork quilt of either grants or equity or whatever kinds of producer-based alliances that one can stitch,” he says.

“The main thing required is public-funded support for independent films in India, and also a distribution strategy, especially for films that have to do with ecology.”

Poacher (2024) is about the ivory trade, which was co-produced by Alia Bhatt

Poacher (2024) is about the ivory trade, which was co-produced by Alia BhattNext, the film should not be too pedantic or preachy, but be ‘Trojan horses’ where you can “sneak in conversations with people who don’t want to have them, and emotionally move them”, adds Sen.

“Ideally, in order to make ecological issues sexy, you need mainstream cinema with stars, and entertaining formats to reach the widest number of people,” says Shedde.

“Haathi Mere Saathi, which I saw as a kid and comments on animal cruelty and zoos, would now be considered politically incorrect as Rajesh Khanna raises wild animals at home instead. But more recent mainstream films like Prabu Solomon’s Kumki [Trained Elephant, Tamil, starring Vikram Prabhu, 2012], have tried to be more mindful towards wildlife, and made a Hindi version for Eros in 2021. But Walt Disney’s animation feature Jungle Book of 1967, which has many versions, remains an all-time favourite that is hugely entertaining yet thoughtful.”

And finally, distribution: The OTT revolution has had a stark impact on the appetite for non-fiction work globally, but, as Sen points out, much of this is skewed towards true crime or reality TV.

“Creative documentaries haven’t got their time in the sun, but at the same time, they also have a house. I’m not euphoric about it, but cautiously optimistic,” he says. “Of course, India’s undeniable success in recent years with various films have moved the needle somewhat.”

Power, responsibility, profit

The Indian film industry is still facing a post-Covid crisis of sorts, with several headliner films opening to lukewarm audience response. At the same time, India is battling record heatwave after record heatwave, and as the climate crisis worsens, India’s majorly agricultural land could see wide-ranging ramifications. While India has always prided itself on its traditions that share a deep connection with its land and nature, its cinema has always been about ‘entertainment, entertainment, entertainment’, with a sprinkling of raising awareness, mostly for social or moral issues.

While India has always prided itself on its traditions that share a deep connection with its land and nature, its cinema has always been about ‘entertainment, entertainment, entertainment’, with a sprinkling of raising awareness, mostly for social or moral issues.Is there a fair onus on the industry to take on climate narratives?

“It would be good if the film industry could take up environment issues, but there are so many other issues as well, including patriarchy, misogyny, child abuse, child labour, etc that need to be addressed: I am not sure the industry is amenable to pressing issues, especially in hard times for the industry,” Shedde says.

Jain, however, offers the flip side: That, perhaps, the industry is likely to struggle further if it stays far removed from reality. Instead of aping Hollywood-style action or sci-fi flicks, Indian filmmakers could go back to relevant Indian issues and culture.

“The Andhra film industry is not struggling, because they are able to resonate with the audience in the way that Hindi cinema used to in the 1970s,” he adds. “Hindi filmmakers seem to have lost touch with the masses. We need to go back to basic issues—the best example of this is Lagaan, which had great music, addressed cultural, rural and ecological issues, and connected with people at so many levels.”