Return to Office: Will women continue to pay a price for flexibility?

Negotiating the new, evolving rules of the workplace can be especially tricky for women. But there is a war for talent, and companies are going back to the drawing board to address concerns

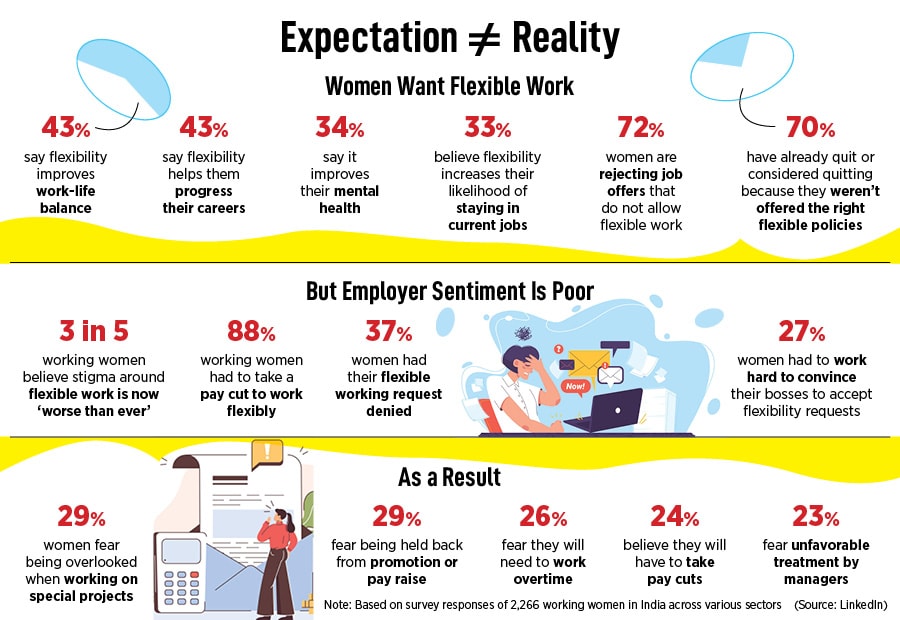

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, even as women continued to suffer more job losses than men, corporate leaders were confident that the future of work is remote and flexible, and saw it as an opportunity to fill gender diversity and inclusion gaps.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, even as women continued to suffer more job losses than men, corporate leaders were confident that the future of work is remote and flexible, and saw it as an opportunity to fill gender diversity and inclusion gaps.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

In Ahmedabad, Shreya Jasani is worried. The 27-year-old MBA graduate was a relationship manager with Citibank in Mumbai when the Covid-19 pandemic struck and she relocated to her hometown in Gujarat. Two job switches later, she is now a campaign portfolio manager with travel arrangements company InterMiles (formerly known as JetPrivilege). Jasani got married in July last year. She stays with her in-laws and cannot go back to the office in Mumbai.

Job opportunities in Ahmedabad offer compensation that is way less for her level of skills and experience, and interviews with companies in Mumbai get stuck at the point where she requests for flexible work. “My current office has not called me back yet, but eventually they will. I am not finding better jobs here in Ahmedabad. My only way out is to look for companies outside that offer flexible and remote work opportunities… but I feel like my career will hit a hard-stop.”

In Mumbai, Rashi Kapoor (name changed), 30, has started going to the office three days a week. A chartered accountant working with one of India’s largest private sector companies, she not only has to compulsorily spend nine hours in office—as per the punch-in/punch-out system of pre-Covid days that is still enforced—but many a times she is given work even after she gets back home. Over and above, she spends at least two hours commuting to and fro on the local train, and has housework to do once she gets back.

“Even if we come back to office, do we really need to continue practices exactly as they were in the pre-Covid days, even if they do not make sense anymore as an indicator of productivity?” Kapoor asks. It does not help, according to her, that the company leadership is dominated by men. For most working men, going to the office is just a question of getting out of the house, and not having to care much about anything else. They shoulder domestic or care responsibilities only when it is convenient to them, Kapoor says. “But it is not so for women,” she explains, adding that companies need to be mindful of the nuances of such systemic gender expectations as they take employees through this period of transition at the workplace.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, even as women continued to suffer more job losses than men, corporate leaders were confident that the future of work is remote and flexible, and saw it as an opportunity to fill gender diversity and inclusion gaps.

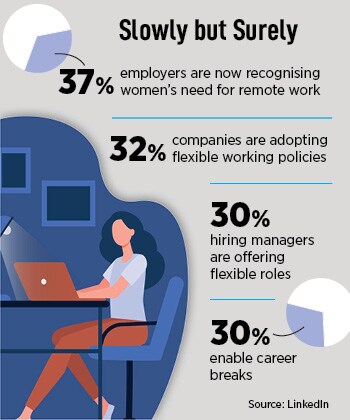

Both companies and employees are doing some soul-searching, she explains. While the latter is relooking at their sense of purpose and putting flexibility front and centre in job negotiations, companies are letting go of their rigidity as they struggle to hold on to people given the ongoing

Both companies and employees are doing some soul-searching, she explains. While the latter is relooking at their sense of purpose and putting flexibility front and centre in job negotiations, companies are letting go of their rigidity as they struggle to hold on to people given the ongoing