Schools have been shut for over 500 days. Bringing rural kids back will take more than just reopening them

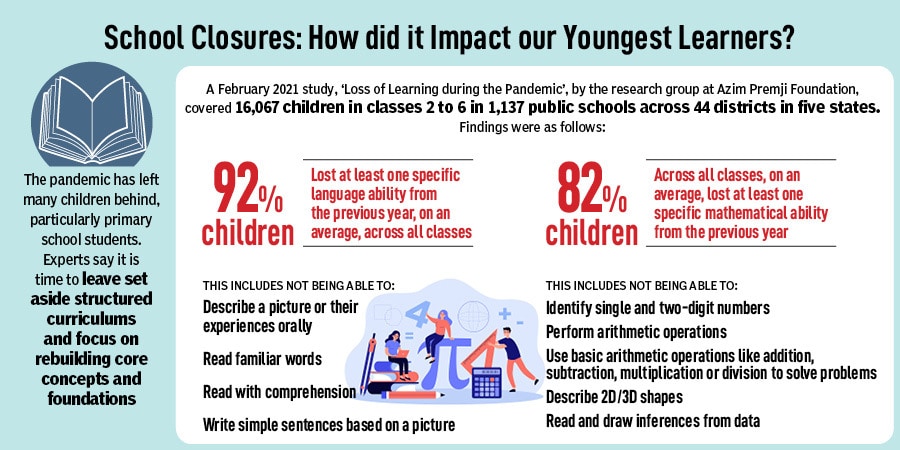

Closure of schools has had a devastating impact on the education and mental health of students, particularly underserved children. The way forward involves decentralising decision-making, helping kids catch up with core concepts, and implementing mitigation strategies at the most local level

Reopening of schools is non-negotiable with a view of the long-term needs of the future generation, experts say, but at the same time, it's important to track the level of Covid-19 infection in the community and prepare the school environment accordingly; Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

Reopening of schools is non-negotiable with a view of the long-term needs of the future generation, experts say, but at the same time, it's important to track the level of Covid-19 infection in the community and prepare the school environment accordingly; Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

In Urmal village in Jharkhand, there are close to 200 students studying in Classes 1 to 8. Many people in the village are illiterate farmers or landless labourers who are not very involved with the education of their children, says science teacher Subhash Chandra, who has always had to incentivise parents through mid-day meals, clean uniforms and free textbooks to ensure they kept their children enrolled in school.

Now, over the past 1.5 years, ever since the first Covid-19 lockdown in March 2020, Chandra and fellow teachers have been going door-to-door to speak with parents and ensure their children do not drop out of school. They have also been home-delivering worksheets.

Online education is out of the question for many children in the village, as their parents struggle with poverty. “Jisko paet paalne ka chinta rehta hai, woh kahaan se internet aur Android phone lega?” asks Chandra. How can someone leading a hand-to-mouth existence buy Android phones or access the internet?

Even in the rare cases that children have had access to a smartphone, classes have had to be held in the evenings, when parents return home after work and hand over their phone to the kids for teachers to contact them. Besides, many a times, now parents send their kids off to the fields for livestock grazing at the time they would have been in school, so kids routinely lose those three-four hours of study time too, Chandra says. “Bahut nuksaan hua hai,” he rues. Children have really lost out a lot.

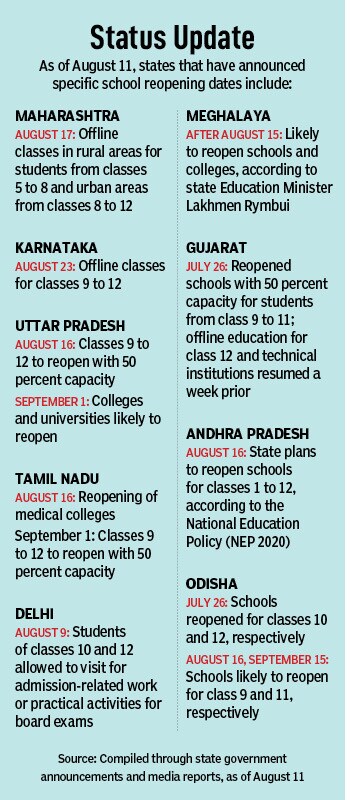

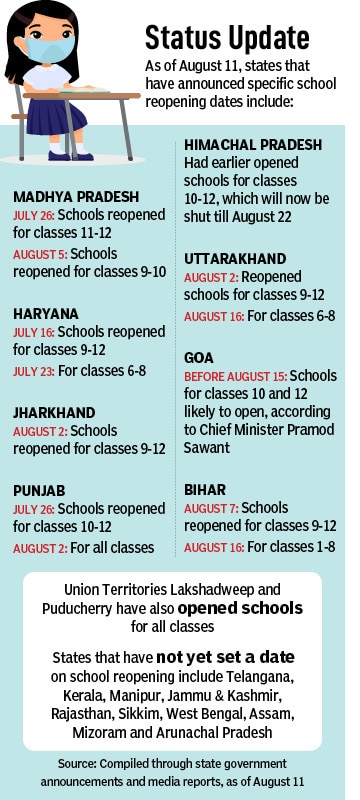

Jharkhand reopened schools for Classes 9 to 12 on August 2. The other classes are waiting for government guidelines, Chandra says, “Yahaan toh sab chahate hain ki school khul jaaye.” Everyone here wants schools to reopen. For parents, it means putting their kids on a path away from illiteracy and poverty. For teachers, it is a way to make sure children actually learn and benefit from education.

Jharkhand reopened schools for Classes 9 to 12 on August 2. The other classes are waiting for government guidelines, Chandra says, “Yahaan toh sab chahate hain ki school khul jaaye.” Everyone here wants schools to reopen. For parents, it means putting their kids on a path away from illiteracy and poverty. For teachers, it is a way to make sure children actually learn and benefit from education.

An average state in India has about 50,000 schools, he explains, so one common decision to either open or shut them cannot be taken, and the strategy has to be one that gives more autonomy to the district or city / village-level officials [like gram panchayats in rural areas and municipal corporations in urban areas], parents, teachers and SMCs.

An average state in India has about 50,000 schools, he explains, so one common decision to either open or shut them cannot be taken, and the strategy has to be one that gives more autonomy to the district or city / village-level officials [like gram panchayats in rural areas and municipal corporations in urban areas], parents, teachers and SMCs.