Sports and mental health: When trophies and fame are lined with silent, dark struggles

More athletes are opening up about their struggles with mental health, even at home. But what makes them vulnerable in the first place, and how should the ecosystem step up?

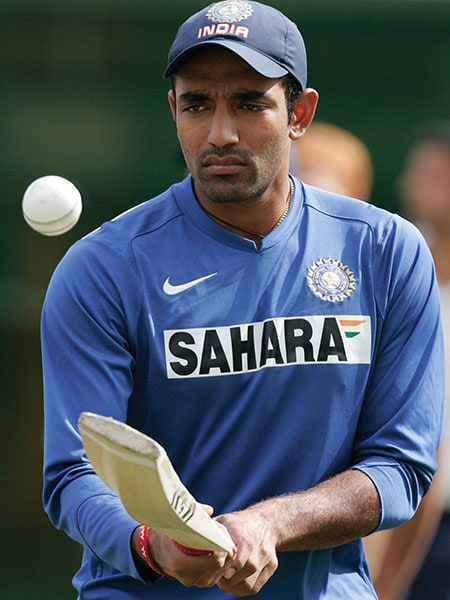

Around the time, in 2011, he was being signed up by Indian Premier League (IPL) franchise Pune Warriors India for a whopping Rs 10 crore, cricketer Robin Uthappa would spend days curled up in bed, willing the world to shut him out. In three months, he changed his phone number so often that his friends and peers couldn’t keep up. “I lost touch with everyone in the cricketing fraternity,” he says. On really bad days, he would open his balcony door, mark a run-up and tell himself he would jump off on the count of three. “I’d count up to two and then something in me would say ‘wait’,” he adds. “It didn’t matter how much I was earning. It did nothing to alleviate the pits of depression I was in.”

After going through similar bouts for five to seven months, Uthappa sought help. In 2012, he reached out to a counsellor, who he had seen in 2009, but stopped thereafter. “Stopping treatment back then was a mistake. With mental health, there’s no quick fix. You have to stay with it till you get to the root and address it,” says Uthappa. “This time, I met her every week, took medications regularly.”

It took Uthappa five years to heal—through victories in the Ranji and the Vijay Hazare trophies, and winning the Orange Cap as the highest run-getter in the IPL, but also days of freefall. In 2018, he began to share his journey “because I felt like I was overcoming all that I’ve been through”.

The 35-year-old is among the earliest of Indian elite athletes to open up on a subject that’s considered a taboo in society, especially among sportspersons. In public perception, athletes are equated with endless resilience, and ideas of mental strength and mental health are conflated. Even some years ago, every discussion on mental health would swing between the flippant and terse, and conclude with, as Uthappa says, either “manage kar lo [manage it]” or “khel par dhyaan do [focus on the game]”.

But repeated assertions from decorated international athletes—from American swimmer Michael Phelps and tennis legend Serena Williams to former NBA star Jerry West and Australian cricketer Glenn Maxwell—have kept the subject alive and chipped away at notions that likened depression or anxiety to merely defeat. Phelps’ bouts came along even as he picked up Olympic golds at will, while Williams conceded in 2011 that she was “miserable” following her Wimbledon victory the previous year. And recent confessions from Virat Kohli and Sachin Tendulkar about loneliness through bad patches, despite their stature as cricketing divinity, have begun to normalise conversations around mental health.