The commodity cycle has turned. Will the momentum sustain?

After collapsing during the pandemic, commodity prices have bounced back quickly, but don't show signs of a super cycle as yet

Image: Giles Barnard/Construction Photography/Avalon/Getty Images

Image: Giles Barnard/Construction Photography/Avalon/Getty Images

Last March, as the world economy shut down, commodity producers knew they were in for a harrowing time. Demand fell off a cliff and producers scrambled to cut capacity. Mines shut shop, rolling mills ground to a halt and oil transporters had to pay buyers to take delivery.

One year on, they’ll readily admit the speed of the bounce back in prices (and demand) has caught them by surprise. While a part of the surge in prices is on account of the ‘everything rally’ phenomenon that commodities along with other assets from stocks to bitcoin and gold to oil have been swept into, a part of the increase in demand is on account of inventory restocking as well as anticipated spending on infrastructure.

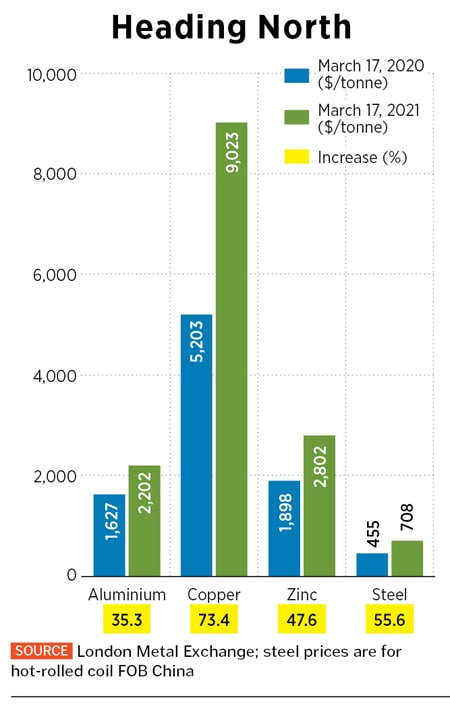

The net result is that prices look set to stay elevated for an extended period. Already some commodities have hit prices last seen at their past peaks. At $175 per tonne, iron ore costs as much as its 2012 peak. Copper prices are up by 70 percent in the last year to $9,100 a tonne and oil has doubled in the last year to $70 a barrel. “Even now, demand continues to surprise. This, coupled with inventory restocking, has led to prices rising,” says Naveen Mathur, director, commodities, Anand Rathi.

This sharp swift rise has stoked inflation expectations, which were largely absent from the developed world for the last decade. Commodity bulls are asking whether we could be in for a commodity super cycle—an extended period of prices rising for years, even decades. Exchange-traded products that track commodities are proving to be popular again. These were popular in the 2000s before falling out of favour after 2014. A point to note is that the price rally looks steep on account of an extended downcycle. Adjusted for inflation, oil, copper and iron ore are still off their peaks. Most commodities are globally traded and prices often track a global benchmark.