- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Westland and Pratilipi found each other a year ago. Can they make it work?

Westland and Pratilipi found each other a year ago. Can they make it work?

Ever since it forged a partnership with digital startup Pratilipi to stay alive after being shut down by Amazon, Westland's strategy has been to embrace new, tech-forward ways of working, while holding on to the gumption that made them stand apart in the competitive publishing industry

Divya writes about gender, philanthropy, startup and workplace trends, and business from the lens of its impact on people. She is keen to find interesting stories and new ways of telling them. A journalism graduate from Mumbai who was previously with The Economic Times, Divya is also an editor and proof-reader. Outside of work, she likes to travel, read books, drink hot chocolate, and endlessly watch, read and talk about cinema.

- For businesses, sustainability should be a leadership challenge, not a cost problem: Rajeev Peshawaria

- Philanthropy for mental health should focus more on community-led models

- I was never taken seriously as someone who can build a business: Masoom Minawala

- Indian companies should focus on high value manufacturing: Vijay Govindarajan

- Roop Rekha Verma's unwavering fight to uphold constitutional values

(From left) Gautam Padmanabhan, CEO of Westland who is now the business head of Westland Books at Pratilipi; Karthika VK, publisher, Westland; Ranjeet Pratap Singh, co-founder and CEO, Pratilipi

(From left) Gautam Padmanabhan, CEO of Westland who is now the business head of Westland Books at Pratilipi; Karthika VK, publisher, Westland; Ranjeet Pratap Singh, co-founder and CEO, Pratilipi

She is one of the most powerful publishing editors in the country, and it is intriguing to hear Karthika VK say that a book can be more than just a book.

“There are a lot of things we can do with a story by extending it into other formats. The essence of it remains the same but it transforms into a whole other experience when it becomes say, a show or a comic or an audio book, and finds different audiences. We are also experimenting with the reverse: Making books that had a first life in another format, like a podcast," says the publisher of Westland Books.

Karthika has adopted this new way of working over the past few months, after her decades of success as a traditional publisher of books was briefly upended in February last year, when ecommerce company Amazon announced that it was shutting down publishing house Westland, a wholly owned subsidiary of Amazon Eurasia Holdings SARL, from March 31, 2022.

It was a bolt out of the blue for India’s publishing industry, and Amazon did not publicly disclose specific reasons for closing down one of India’s significant and respected publishing houses. It deepened the fears of people about the various challenges India’s trade publishing industry faces, such as decline in number of readers and their changing preferences, increasing competition from foreign publishers and the rise of e-books. As Sharanya Manivannan, an author with Westland, tells Forbes India over email, “It deeply disillusioned me about publishing itself, both as an act and as an industry.”

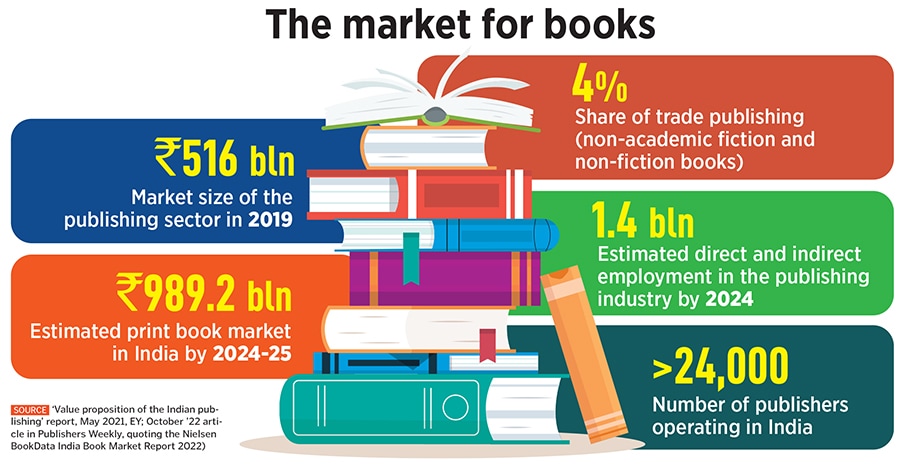

India’s print book market will hit Rs989.2 billion by 2024-25 and there are more than 24,000 publishers operating in India, says an October 2022 article in Publishers Weekly, quoting the Nielsen BookData India Book Market Report 2022. Of this, trade publishing (non-academic fiction and non-fiction books) accounts for only 4 percent. The largest share of 71 percent is the school sector, while higher education is 25 percent.

Three major players in India’s trade publishing business—Penguin Random House India, HarperCollins India and Westland—each publish hundreds of titles every year. A closure of one of them, therefore, sent shock waves, with many authors staring at an uncertain future of whether their books would be pulped and go out of print.

Karthika and her colleagues immediately started making calls to their authors when news went out, assuring them that Westland was trying to find a way out of the crisis, and also offered them the freedom to move on to other publishers and find homes for their books, if they so wished.

At the same time, Ranjeet Pratap Singh, co-founder and CEO of digital self-publishing platform Pratilipi, rushed to acquire Westland from Amazon as soon as he heard the news of the closure on social media. But because of “timeline constraints”, he decided to start from scratch and form a new partnership with Westland instead. Build a new entity, while retaining the strength, reputation and ethos of one of India’s oldest publishing companies.

This marked the coming together of two entities that were same to the extent of being in the publishing space, but otherwise wildly different from one another. While Pratilipi puts out user-generated stories on its website and app, primarily in Indian languages, Westland is known to have published a mix of the most popular, carefully researched and hard-hitting literary, non-fiction and translation works of our time. Their roster of authors has included Perumal Murugan, Rukmini S, Christophe Jaffrelot, Josy Joseph, Anuja Chauhan, KR Meera, Revati Laul, Aakar Patel, Nalin Mehta, Chetan Bhagat, Amish Tripathi and Union minister Smriti Z. Irani.

Karthika says that close to 75 percent of Westland’s authors have decided to stay with them, and they have about 180-odd titles from the old lists that are already back in stores since they started the partnership with Pratilipi.

“Scale is important for all publishers and it’s no different for Westland. Fortunately for us, we are not starting from zero. We have a strong backlist of authors,” says Gautam Padmanabhan, CEO of Westland who is now the business head of Westland Books at Pratilipi. “But as we go along, scale may not necessarily come from traditional publishing, but from the ability to adapt content into different formats. I think that’s where we are uniquely positioned.”

Also read: Regional podcasts find their voice

Synergies and Experiments

When Singh co-founded Pratilipi along with Sankaranarayanan Devarajan, Prashant Gupta, Sahradayi Modi and Rahul Ranjan in 2015, he was in his 20s, and had one major goal: Democratising storytelling. Growing up in Fattepur, a village about 60 kilometres southwest of Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh, he had seen his uncle often save money to publish his writings in Hindi. He realised that in India you many-a-times had to pay the publisher to get your works published.

He built Pratilipi as a way to build products and platforms where “anybody can come and share their story with the rest of the world in any language or format, across geographies”, Singh says. To meet this end, apart from having its own self-publishing platforms for audio and literature, Pratilipi has acquired IVM Podcasts and publishing company The Write Order. They have a vertical for comics and graphic novels too.

The Bengaluru-based startup, which has raised close to $80 million in funding so far, counts Nexus Venture Partners, Omidyar, Meesho Co-founder Vidit Aatrey, Unacademy Co-founders Gaurav Munjal and Hemesh Singh, and Delhivery Co-founder Sahil Baruah as investors. Pratilipi has 250,000 paid subscribers, claims Singh, adding that paid users spend three hours daily on an average on the platform, and the top four languages of the platform are Hindi, Malayalam, Tamil and Marathi.

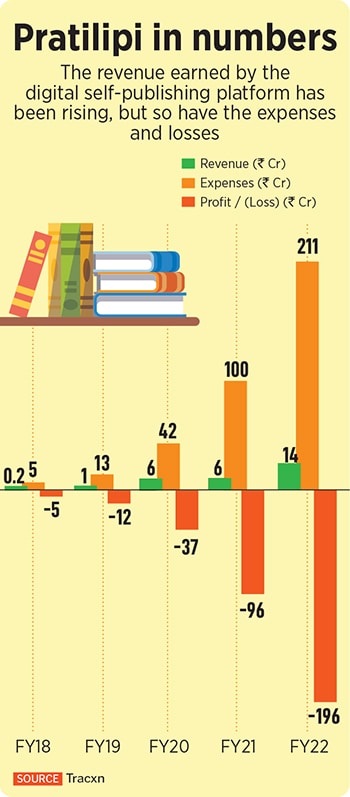

As per data sourced from Tracxn, the startup’s revenues have increased from Rs2.5 lakh in FY16 to about Rs14 crore in FY22. Losses have ballooned too. From Rs96 lakh in FY16 to about Rs196 crore in FY22. Over the past year, the total expenses of the platform increased from about Rs100 crore in FY21 to about Rs210 crore in FY22. Westland would be about 10 percent of their total expenses, says Singh.

Pratilipi’s revenues are increasing every month, and the company is on course to be profitable by the end of next year, believes Pratik Poddar, partner, Nexus Venture Partners. The venture capitalist says that the company’s subscription programme has high engagement and repeats from paid users. He explains that long-term profitability would come with IP [intellectual property] sales, partnering with OTT platforms and producers. “In the next few years, we expect Pratilipi to prove IP monetisation, support a high quality, sticky paid user base, and become self-sustainable,” he says.

The idea of getting Westland into the business mix is primarily to help Pratilipi strengthen their offline play, and at the same time, explore possibilities of some of Westland’s popular books for IP creations like movies or TV series, apart from other avenues like audio books and comics or graphic novels. It will work the other way around as well: Stories that have done well as comics or audio or on the Pratilipi self-publishing app will be published as physical books. “Basically, it is a two-way collaboration while the Westland team will largely work independently when it comes to taking calls about publishing,” Singh says.

In March, the company launched a new language imprint, Pratilipi Paperbacks, as an effort in this direction. The top-performing or most-read novels on the Pratilipi app will be picked up for publishing. The imprint mostly has pulp fiction narratives in genres like thriller, horror and romance, says Minakshi Thakur, publisher (Indian language division), Westland Books, who is heading the Pratilipi Paperbacks imprint.

A senior industry professional with close to 20 years of experience, Thakur had set up Eka, Westland’s language imprint that published original text and translations in nine Indian languages and English. “What is very different here is that I have published popular writing in the past, particularly in Hindi, but those writers were not working on an app,” she says, referring to the shift from Eka to Pratilipi Paperbacks. The voices of writers on Pratilipi is fresh and completely new, she says, and the language and stories is hyperlocal. “I was under the impression that there is no editorial intervention here, but some of these writers are very good and have interesting stories to tell. So it was not a lot of work for us.”

This imprint specifically targets Tier-II cities and beyond, and the books will be “priced low”, Thakur says. She adds that there used to be local publishing houses in India that specifically published crime and pulp fiction works for a generation of writers, but it’s hard to find them today. Meerut in Uttar Pradesh, she says, was the capital of crime fiction publishing. “But there is no competition in this segment right now, so if we are able to crack this, it’ll be great,” she says.

Pratilipi Paperbacks has so far released nine titles in Hindi, Tamil and Bengali, including three novels by Rajesh Kumar, a popular crime writing author in Tamil, who was written over 1,000 novels and novellas, and books by crime fiction and web series writer Amit Khan. It’s too soon for trade numbers as the books are just getting launched in the stores, but many of these writers have a community of ‘Superfans’ on the Pratilipi app, Thakur says, a lot who are picking up these books. They have plans to launch more books over the course of the year, including in Marathi, Malayalam and other Indian languages.

As an investor, he remains “bullish” about the prospects of Pratilipi, says Aditya Misra, director, Omidyar Network India. According to him, Pratilipi is addressing the barriers that the Next Half Billion (NHB), particularly women, face in going online. “Besides enabling hundreds of thousands of Indian language writers to build a large viewership and augment income by monetising their IP across multiple formats, Pratilipi is an important proof-point in creating an inclusive and trusted online space for women,” he says, in a written response. Singh says that about 55 percent active subscribers on Pratilipi are women.

Also read: Bookstores are booming and becoming more diverse

Moving Forward

There’s a running joke in office that Singh was not even born when he started working, says Gautam. The veteran publisher adds that the transition has been seamless for him and his team. After all, for Gautam personally, this is the third major shift of his career.

Westland started as a family business by his father, KS Padmanabhan, in the 1960s, as a distributor of foreign books before it started publishing its own. In in the 2000s, it was acquired by the Tata group, and then by Amazon in 2017. “One common thread in all these experiences is that there’s always going to be a phase where you have to understand the thinking of the organisation and their culture before you settle down,” says Gautam. “I think with Pratilipi, we have settled down pretty fast.”

He also adds that no matter who the owner, Westland has always maintained its independence and published voices of authors it believed in, particularly Indian writers in English and other languages. This, he says, will continue. Singh says that Gautam and Karthika will have “99.9 percent” independence about what happens at Westland, and he will have the power to veto a decision only “if it is something that actively hurts the interests of Pratilipi”.

In fact, when Amazon shut it down, there was speculation on social media about whether it was due to Westland publishing authors with bold anti-establishment voices. But Karthika says that this is only one of the possibilities. “Perhaps it was business compulsions that made it happen, perhaps it was a lack of recognition of how crucial it is to have and to amplify such voices in the times we live in,” she says.

In fact, when Amazon shut it down, there was speculation on social media about whether it was due to Westland publishing authors with bold anti-establishment voices. But Karthika says that this is only one of the possibilities. “Perhaps it was business compulsions that made it happen, perhaps it was a lack of recognition of how crucial it is to have and to amplify such voices in the times we live in,” she says.

What happened with Westland should not be viewed as part of a pattern or a significant precedent, according to her. “It was a shock to all of us because none of us had even heard of a publishing house being shut down in recent times, especially when money was not the issue. But I don't think it can be seen as a pattern. Most publishing houses that have been in the business for a while believe that publishing is crucial for fostering debate, conversation, ideas, and freedom of expression.”

Authors, literary agents and people in the trade continue to stand by Westland, and a lot of it has to do with the strong relationships that Karthika and Gautam have built over the years.

Literary agent Mita Kapur, who has 11 authors with Westland, says that she respects how they are always on the lookout for fresh voices, and stick to pragmatic, hyperlocal approaches when it comes to the marketing of books, rather than promising things they cannot deliver. “They are taking on fewer books and are consciously taking one step ahead at a time. I can only see them getting bigger and selling their books better in the future,” she says.

Amrita Mahale, whose debut work Milk Teeth released to a lot of appreciation and acclaim in 2018, says she has continued with Westland because she has “blind faith” in Karthika. It was she who turned a “messy manuscript” into the book that it is today. “She has a special talent for seeing the hidden potential in a book,” says Mahale. “She is genuinely warm, caring and a good person. Her relationship with authors never felt transactional.” In fact, Mahale signed on with Pratilipi and Westland for a bonus that was slightly lower than her first advance, but says the book is four years old and she found the terms of the contract fairly identical to what she had before.

“I really do feel Westland is the best publisher for Indian authors who work in English right now. They navigated the Amazon crisis with grace, they are transparent when it comes to financials, they take risks (whether those are political, such as books that challenge authorities, or creative, such as translations),” writes Sharanya over email. Her graphic novel, Incantations Over Water, was republished by Pratilipi last year, and she is waiting for her picture book Mermaids in the Moonlight to return to the shelves.

She says writers in general, across the industry, have limited bargaining powers, but her contract with Pratilipi is more “writer-forward” compared to the one she had earlier when Amazon was in the picture. She says, “Over the past year, ever since Pratilipi came into the picture, we have interacted a little less, but the constant and candid communication through the Amazon-related crisis continues to give me confidence in the company.”

As investor Poddar of Nexus Venture Partners puts it, “The partnership could be very exciting. Early days, of course.”