Why an Indian owner of an elite football club could be a win-win

Some of the most popular European leagues, with towering viewership, could be a global platform for branding, while an exchange of ideas and knowhow can trickle down to improve grassroots football in India

The Old Trafford stadium, the homeground of Manchester United. The club, which has 13 Premier League titles, has been put up for sale by its current owners, the US-based Glazers family

Image: Ian Kington / AFP

The Old Trafford stadium, the homeground of Manchester United. The club, which has 13 Premier League titles, has been put up for sale by its current owners, the US-based Glazers family

Image: Ian Kington / AFP

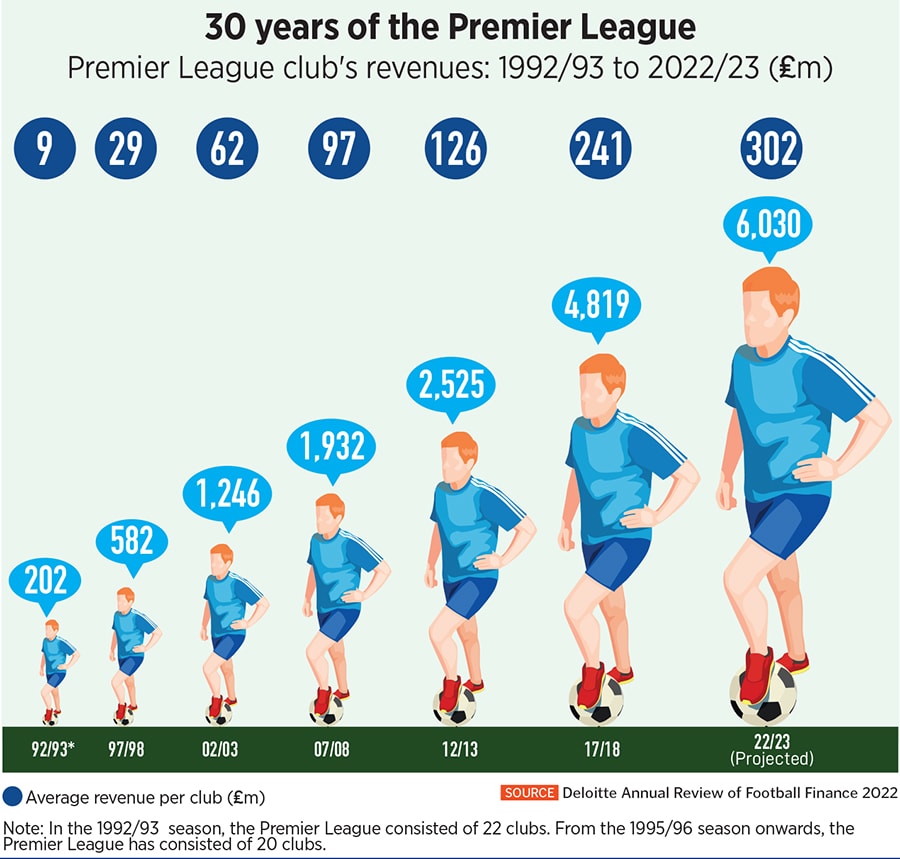

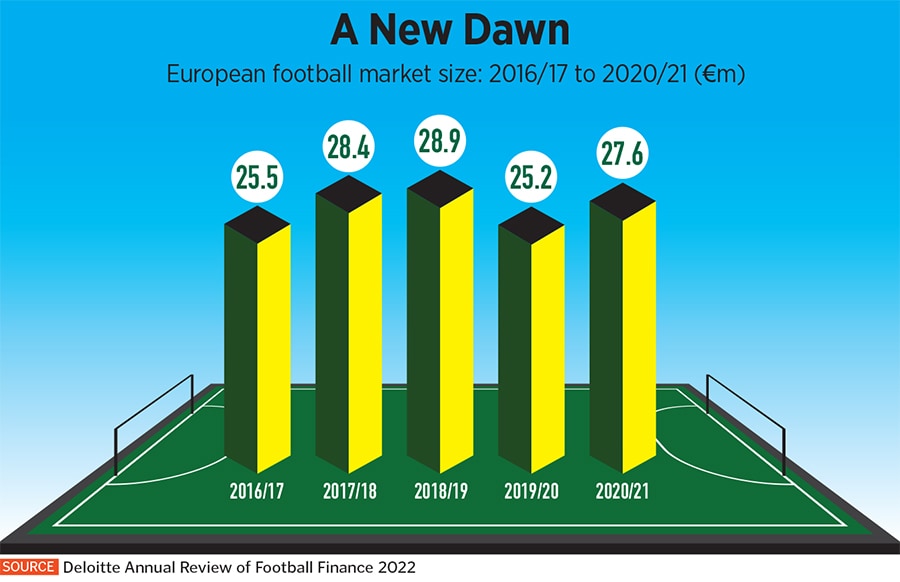

The Premier League (PL), England’s top domestic football league, might have gone on a month-long break to accommodate the Fifa World Cup, but two of its most storied clubs are engaged in frenetic activity, albeit on the side lines.

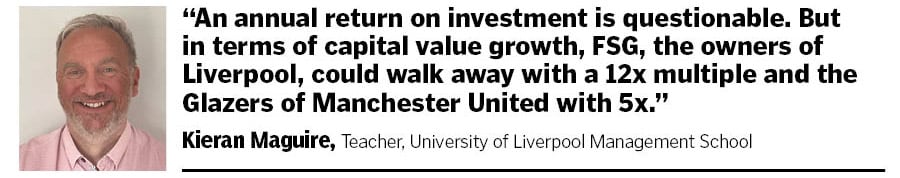

Manchester United, which has won the league 13 times, has been working the headlines double-shift: First, with an explosive interview by its Portuguese superstar Cristiano Ronaldo, railing against the owners and manager Erik ten Hag. Ronaldo has subsequently exited through a “mutual agreement”, but the Glazers family, which bought the club in 2005, continues to remain in the news for putting Manchester United up for sale.

But the Red Devils aren’t the only ones looking for buyers. Early in November, the US-based Fenway Sports Group (FSG), which owns six-time Champions League winners Liverpool since 2010, announced that it was ready to trade hands. Media reports surfaced soon after, claiming Mukesh Ambani, chairman and managing director of Reliance Industries (which owns the Network18 Group that publishes Forbes India), has entered the race for the bid.

While there has been no word yet, it turns the spotlight on Indian billionaires, who are growing in might both on and off the field. As the Forbes’ billionaires’ list published in April stipulates, the total number of Indian billionaires rose from 140 last year to 166 in 2022, while their combined wealth grew by 26 percent to $750 billion.

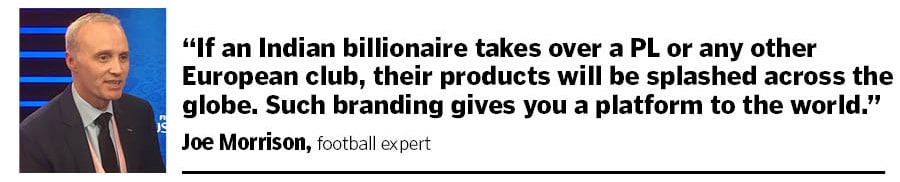

A few of these billionaires, Ambani included, own cricket franchises in India and abroad, while many hold a stake in the homegrown Indian Super League (ISL) that is co-promoted by Reliance. Should Indian billionaires now turn their sights to top-flight football clubs? If you consider the timing, it's a go.

But Seagraves disagrees. He believes it will give Indian football the right kind of exposure to take off. When he came to India 10 years ago to train kids and help them play in foreign clubs, he realised there was no real infrastructure and professionalism for that. “If an Indian guy could go to Europe and bring those coaches over, even on a small scale, it might set the ball rolling for bigger things,” he says.

But Seagraves disagrees. He believes it will give Indian football the right kind of exposure to take off. When he came to India 10 years ago to train kids and help them play in foreign clubs, he realised there was no real infrastructure and professionalism for that. “If an Indian guy could go to Europe and bring those coaches over, even on a small scale, it might set the ball rolling for bigger things,” he says.