Will India's Rs 7.5 lakh crore capex solve its job crisis? Maybe not

Public capex constitutes only 20 percent of the total capex, and the outlook for private investments—nearly 80 percent of total capex and which play a crucial role in expanding the economy and creating employment—remains lacklustre

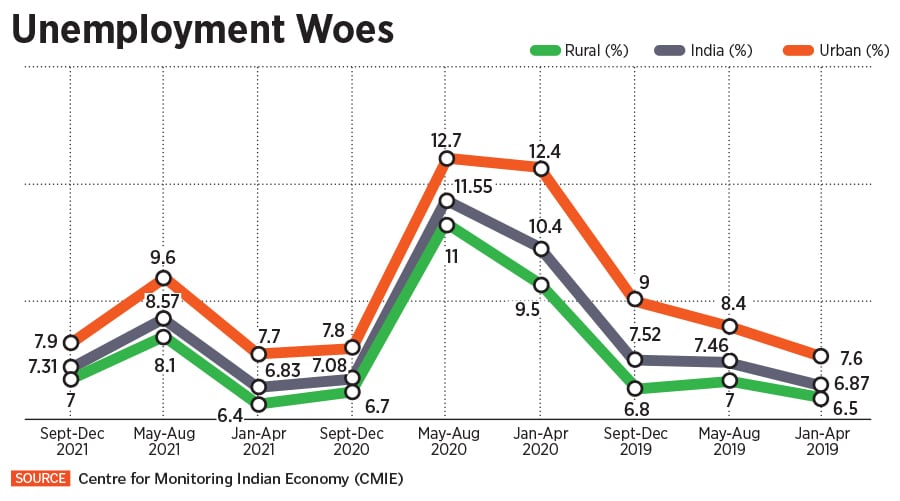

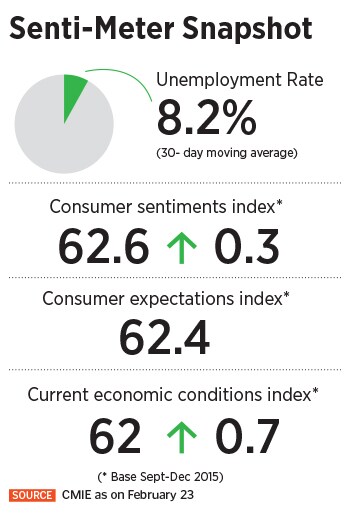

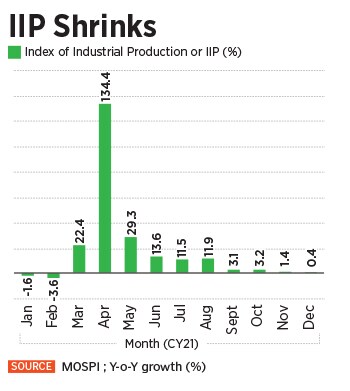

Tepid consumption, a lull in economic activity (see chart), and the lack of an urban safety net for migrant labourers has worsened the situation and high unemployment has been a key concern

Tepid consumption, a lull in economic activity (see chart), and the lack of an urban safety net for migrant labourers has worsened the situation and high unemployment has been a key concern

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

India is staring at a worrisome job crisis which underlines deep structural issues and the ill-effects of rising inequality. Millions of workers, pushed to the brink, have moved to low-paying farm jobs from more productive sectors of the economy for daily sustenance.

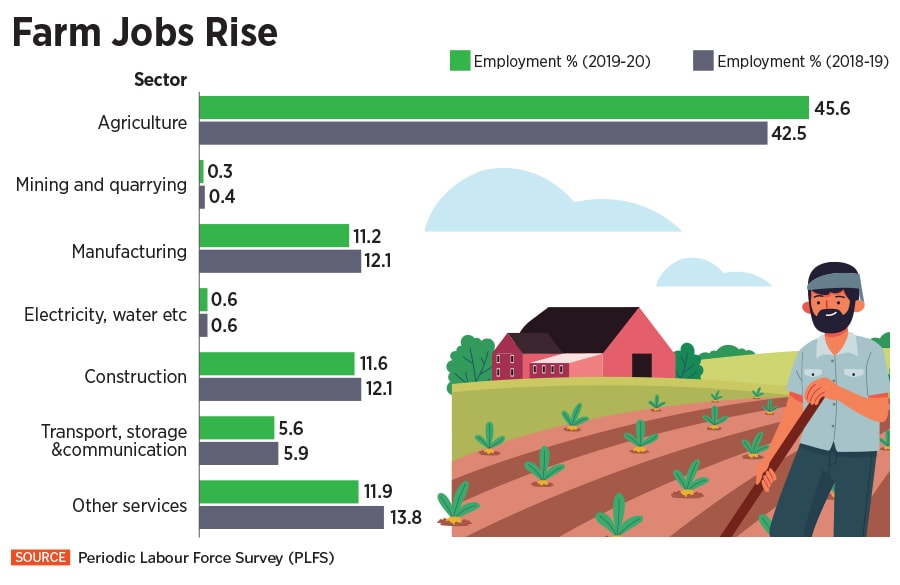

The latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for the 2019-20 period corroborates this alarming trend. It states that jobs in agriculture rose to 45.6 percent from 42.5 percent in the previous year. However, employment across manufacturing and construction declined during the same period (see chart).

Mahesh Vyas, MD and CEO, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), explains why this is a troubling trend and how it could be a sign of hidden unemployment.

“Employment in the non-agricultural sectors has stagnated and even declined. As a result, people have moved back to the farms. Now, this is very peculiar to India. In most countries when jobs shrink in the industrial parts of the country it leads to high unemployment. In India people just move back to the farms. And when people move back to the farms it is not that they produce more agricultural output. It is the productivity of labour that falls, because most of the people moving back to the farms are actually engaged in disguised unemployment,” Vyas says.

The big capex bet

The big capex bet

While corporate balance sheets have improved, there is a lot of uncertainty around government policy and economic growth. For example, commodity prices are increasing, there is geopolitical tension, central banks are changing their policy stance, etc. In turn, it is hard to forecast how growth will pan out given the volatility. And this is what is coming in the way of private investments and hence job creation, observes Bhandari.

While corporate balance sheets have improved, there is a lot of uncertainty around government policy and economic growth. For example, commodity prices are increasing, there is geopolitical tension, central banks are changing their policy stance, etc. In turn, it is hard to forecast how growth will pan out given the volatility. And this is what is coming in the way of private investments and hence job creation, observes Bhandari.