Behind the boom in books on films

New books are taking a more critical look at their subjects

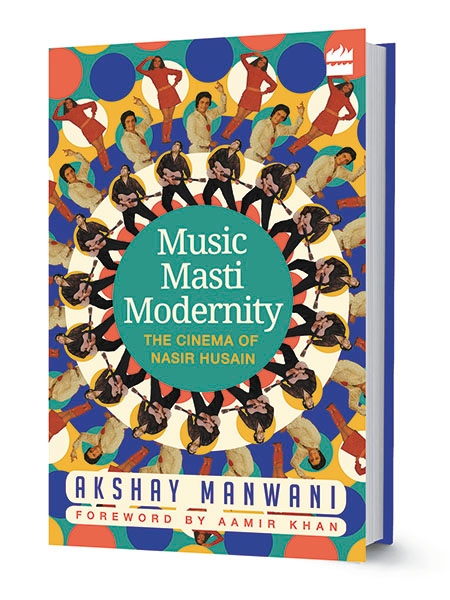

The most entertaining book launch I attended recently was a conversation around Akshay Manwani’s Music Masti Modernity, a study of the director Nasir Husain’s cinema. One panelist here would normally have been the sole cynosure of all eyes, but Aamir Khan wasn’t in attendance as a big movie star; he was there as Husain’s fond nephew, who had acted as a child in the director’s 1973 film Yaadon ki Baaraat. With Husain’s daughter, Nuzhat Khan, and his son, the director Mansoor Khan, also present, this was as much a chatty family gathering as a discussion on the director’s working methods.

Early on, the book’s editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri mentioned that some of the critical writing now being done on popular Indian cinema was reminiscent of the liberating French criticism of the late 1950s—a time when the possibility began to be raised that popular cinema could have artistic rigour, and Hollywood studio directors like Howard Hawks and John Ford could be taken seriously as ‘auteurs’.

This struck a chord, not just because I had read Music Masti Modernity and enjoyed its analysis of scenes and tropes from the work of a filmmaker whom many might dismiss as just another song-and-dance entertainer (in full disclosure: I was interviewed for the book and quoted in it), but also because much of my own reading as a young film buff centred on exactly the sort of writing that Chaudhuri mentioned.

This includes books written in the 1960s by critics who were associated with the pathbreaking UK journal Movie, such as Robin Wood’s intense Hitchcock’s Films, which began by asking the question ‘Why should we take Hitchcock seriously?’ and then proceeded to provide a passionate, book-length answer by closely examining how pet obsessions and visual signatures play out across the director’s work; and VF Perkins’s Film as Film: Understanding and Judging Movies, which showed how the creation of even seemingly straightforward ‘narrative films’ involved many careful decisions at the level of framing, shot composition, lighting, sound and costume—all tailored towards a specific vision.

A much shorter book about a specific film is Anil Zankar’s Mughal-e-Azam: Legend as Epic, about K Asif’s 1960 classic. This monograph combines casual observations about plot with stimulating discussions of the film’s form and mise en scène. In one section, Zankar, with the help of numerous still images, looks closely at the scene where a shackled Anarkali (Madhubala) is brought to Emperor Akbar (Prithviraj Kapoor), and how the use of long shots and close-ups heighten the personal drama of the moment. [Incidentally, Mughal-e-Azam is part of a series that will also see the publication of a book about Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (by Gautam Chinamani) as well as books on Gulzar’s films.] This again suggests a shift in Indian publishing’s conventional wisdom, which used to go: Sure, India is a film-mad country, but the market for film literature isn’t big because most of the people who love mainstream cinema aren’t interested in reading analyses of those films.

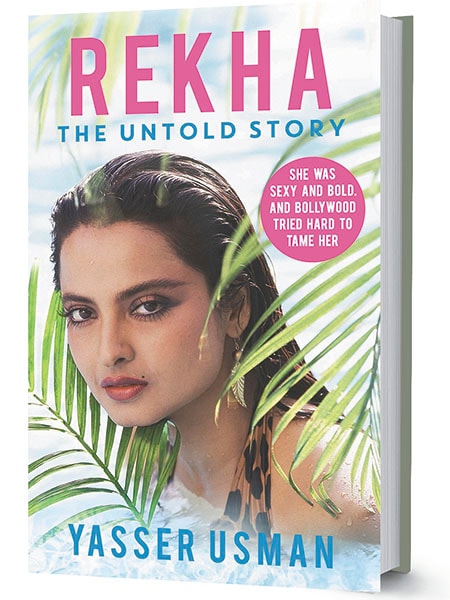

That said, a book about a popular film or film personality doesn’t have to be in analytical mode; it can be in the research-driven, journalistic one. In the last couple of years alone, there has been no shortage of those. Two books about Rajesh Khanna came out at almost the same time. Then there was Rauf Ahmed’s Shammi Kapoor: The Game Changer, an affectionate account of a man whose career turned many of our expectations of the Hindi-film hero on its head; Diptakirti Chaudhuri’s Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema’s Greatest Screenwriters, about the most influential screenwriting partnership in Hindi-film history; and Yasser Usman’s Rekha: The Untold Story, which centres largely on the actress’s personal life.

To a degree, this is also true of Aseem Chhabra’s Shashi Kapoor: The Householder, the Star. Though the bulk of Kapoor’s films were made in mainstream Hindi cinema (at one point he was shooting so many of them simultaneously that his brother Raj Kapoor disdainfully called him a “taxi” who would go anywhere!), Chhabra is more interested in the actor’s work with international collaborators such as Merchant-Ivory. This is perhaps understandable, given that the average Indian movie-buff has had much less exposure to those films, and too many of us grew up thinking of Shashi Kapoor as little more than foil or second lead to Amitabh Bachchan.

The new year will see the publication of the autobiographies of Rishi Kapoor and Sharmila Tagore, among others; also on the cards are ‘authorised’ biographies about personalities who are barely midway through their careers (Karan Johar and Nawazuddin Siddiqui, for instance), but ‘hot’ enough at the present moment that their names and faces on a book jacket will sell tens of thousands of copies. I hope these books—even if they are partly or fully ghostwritten—will capture something of the subject’s voice and be truly personal, and at least somewhat candid, instead of being just public-relation exercises. We already have too much of the latter in media coverage of our cinema.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist

(This story appears in the Jan-Feb 2017 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X