Prague: City of Shadows

Dark and haunted by a bloody past, Prague is a city that can change you

I’m trying to tell you, the travel writers who call Prague a “fairy tale” city are wrong. Explore the enchanting streets lit by gaslight, they write. Hold your lover’s hand while you stroll across the Charles Bridge, and then off into the sunset. Or so they imply.

What’s conveniently left out is the other part of the fairy tale, the part populated by witches and gargoyles and imps. The part where older versions of the Brothers Grimm — Cinderella murders her stepmother, the Little Mermaid kills herself — ring more true.

Prague is dark, filled with grotesque reminders everywhere of its storied, bloody past. And it will teach you a lot, if you let it. I travelled in and out of Prague for six months, but even in an evening, the city can change you. It can also tear you apart.

Like it did Kafka. Prague’s bleakest fiction writer was haunted not only by his evil father, but also the mysterious city which he tried to leave but never could. Not for long.

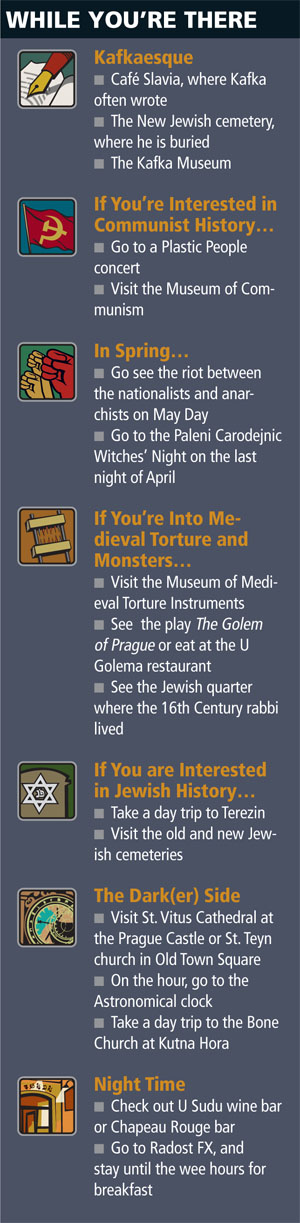

Kafka wrote in the bustling Café Slavia, but his nightmarish style of narration comes from his experiences growing up in its brutal, midnight streets. Prague is truly Kafkaesque, a world that is senseless, surreal, and often dangerous. The city made Kafka one of the most influential fiction writers of all time.

Kafka believed that “the world has gone nuts,” and nowhere is this more evident than on the trams of Prague, which ferry the Czech people from their morning thoughts to their office to their evening pints. It’s here that the effect of the communist past of Prague still permeates.

The older generation that crowds the trams with armloads of grocery bags still very much remembers the random persecution of their friends, their family, themselves. They are disoriented, too, by the new, freer lives they are now allowed to live. They still dress in drab, grey clothing — since when have they been told to wear anything else? — and try not to watch the young couples that neck and straddle one another on tram seats, try not to listen to the new music. The most well-loved rock band of the older generation, The Plastic People, was censored, then banned, and put on trial. The music of my childhood, an old woman on the tram tells me. Which music? I ask. She can’t remember.

An underground Plastic People concert we attend is performed with an air of prohibition. I watch a woman shed grey clothing for an orange mini-skirt, spike her hair, and sing loudly to the opening song. Here, it’s clear, she can forget; the public executions, the years of suffering, the sight of Jan Palach, a student of Charles University, lighting himself on fire.

The new generation, however, has learned from their parents. They know what it means to rebel. On May Day in Prague, the Nationalists prepare for battle against Anarchists in Namesti Miru square (literally, ‘Square of Peace’). They look ready to kill, but they just want to be heard. Sticking their chests out, they knock fists against palms in preparation, separated by a double cordon of riot police. The Anarchists wear masks; the Nationalists wear bare faces. The riot police are covered in enough armour to go to war. By evening, the police are still holding both groups back, but I hear a man say: Next year, I’ll kill someone.

But politics doesn’t matter on holidays. The night before May Day is the Burning of the Witches, where hundreds of Czechs (of every party) gather by the river to set broomsticks and giant effigies of witches on fire. We watch and scream in delight as the fire burns higher, and when it gets too hot, we shed our clothes and jump naked into the water. Lovers and teenagers and old women alike are spurred on by an elation that comes only with wickedness.

The Czech people have never been kind to their witches. In Medieval times, hags, heretics, and state enemies were lucky to be the burned at the stake. The alternative was a “head crusher” or a “beheader.” Or the “Virgin of Nuremburg,” whose spikes penetrated the body everywhere except the vital organs, so a witch would slowly bleed to death. Wandering through the tourist centre, where stall owners despise tourists in spite of (and because of) depending on them, a tilted museum still holds 60 of these torture instruments.

For the Jews, when things got bad, the Golem came to the rescue. According to Czech legend, the Golem monster was created by a 16th century rabbi to defend the Prague ghetto from anti-Semitic attacks. The locals are very serious about the need for the monster, and after a while, I am too. The Jews needed the Golem long after that rabbi’s time. In the garrison town of Terezin, not far from Prague, it’s not the military history that is remembered, but the death of nearly 100,000 Czech Jews. Terezin’s concentration camp killed many of Prague’s brightest. The gas ovens still stand, but what sticks in memory is the thousands of shoes outside the chambers, and watercolour pictures painted by children just before they were gassed.

In Prague, a Jewish cemetery lies half empty, because the generation it was built for never got graves. A film festival shows a movie made by an Austrian Jew about his time in a concentration camp. I look for reactions but the audience is silent, stoic. No one cries. This is life. Maybe it takes a weighted history to understand that.

After several months in Prague, I start to avoid the darkness of the city. I visit tourist sites I missed, believing that it must be only in covert spaces that bleakness rules. But gargoyles peek out of every corner, arch, and gateway, most with thorns attached, reminding you they are there to ward off evil spirits. At St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague Castle, I try to concentrate at the soaring buttresses of the church, but almost trip over the relics of St. Wenceslas. Even the Gothic architecture of my apartment building summons nightmares.

I try to avoid, too, the Astronomical Clock at the city centre, where at every hour, a bell tolls, the windows of the clock fly open, and mechanical figures begin to dance out in frightening, but fateful, disharmony. Twelve mechanical apostles are followed by mechanical skeletons. And then mechanical “sinners,” reminding the watchers of their impending death. As tourists race to snap pictures, Czech thieves make off with their wallets. A local tells me that when the clock was made, the town officials blinded the clockmaker, so he could never duplicate his masterwork.

That’s it. We have to get out, I say. We plan a trip to Prague’s countryside. But the sleepy town of Kutna Hora includes not just silver-makers but also the Church of Bones, a Gothic structure adorned by the remains of more than 40,000 dead. The church was originally a burial site for the bodies left behind by the Bubonic Plague and the Hussite Wars, kept in order by a half-blind monk. Finally, an artist was commissioned to fashion the overload of bones into works of art. A sour-faced tour guide shows us bone bells, bone chandeliers, and garlands of skulls.

And that’s when I realise that I’ve come to like the darkness. Maybe it’s something about that oxymoron, “grotesque beauty.” Or that it’s because what shocks also excites. Or as Kafka believed, it’s that suffering is a necessary element, and it will teach you things.

So we venture into the dark, tripping over cobblestone streets that lead to underground bars, and find a generation of Czech kids dying to get messed up. I don’t know if they do this to shake off the grey suppression of their parents, or if it’s because the reality of the city’s history hurts too much. But the truth of Prague is that pre-teens hunch in every dark corner, swigging beers and smoking forbidden cigarettes until the sun comes up. In U Sudu, a barely lit subterranean wine-cellar-turned-bar, every kind of grass grows and everyone is stoned. Somewhere in the centre of the city, a large-nosed girl tries to stick needles in me in a bar bathroom. I don’t do heroin, I protest. She only laughs at me. This is her happiness.

So we venture into the dark, tripping over cobblestone streets that lead to underground bars, and find a generation of Czech kids dying to get messed up. I don’t know if they do this to shake off the grey suppression of their parents, or if it’s because the reality of the city’s history hurts too much. But the truth of Prague is that pre-teens hunch in every dark corner, swigging beers and smoking forbidden cigarettes until the sun comes up. In U Sudu, a barely lit subterranean wine-cellar-turned-bar, every kind of grass grows and everyone is stoned. Somewhere in the centre of the city, a large-nosed girl tries to stick needles in me in a bar bathroom. I don’t do heroin, I protest. She only laughs at me. This is her happiness.

And the zenith of any evening in Prague, we soon realise, is absinthe. My friend warns me about the drink, the green fairy of Bohemia: It’s 130-proof, and it will kill you. Or it will try. Undeterred, I pour an ounce in a shot glass, and then balance a spoon with a sugar cube on it, waiting for the bartender to light the sugar on fire. I pour the hot mess down until my throat’s in flames. Two Czech men dance nearby, throats burning of absinthe, too, and the city’s history of suffering is written on their faces. One man dances as if he has no bones in his body, the other as if he were a robot-man. I remember that a Czech writer coined the word ‘robot,’ which literally translates to ‘hard work.’ Suffering. It must have been hard to have the city you love controlled for so long, I think. Or maybe it was their parent’s city.

Because these men’s Prague is a free city. Clockmakers are no longer blinded, nor bodies crushed. The gas ovens lie in disuse. While the city still wears, may always wear, a cloak of suffering, their bodies tell it different. In a no-bones-body-swagger dance, the man smiles at me, and tells me that in his Prague, a positive element is coming to life.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)