Keep the Door Revolving On Delisting Norms

If delisting of shares from exchanges is made easier, private equity funds can play a better role in the turnaround of small companies

Do you know that 86 percent of companies listed on Indian stock exchanges, account for only 3 percent of the market capitalisation? The remaining 14 percent, made up of blue chips and market darlings, account for 97 percent of the market cap. This is not different from what it is globally, but there is an additional catch in India.

Ignored by investors and stock researchers, small cap companies can’t raise growth capital or rope in players like private equity firms. “A mid-sized company that wants to do a follow-on public offer will not even be touched with a barge pole by merchant bankers,” says Raja Kumar, the head of private equity firm Ascent Capital.

Yet, it’s no one’s case that these companies are has-beens. There are hidden gems which, with a little outside help, could put themselves back on the path to high growth. Harish H.V., a partner with advisory firm GrantThornton, estimates there are around 100-150 such gems in the 6000-odd small cap stocks.

Infographic: Vidyanand Kamat

Infographic: Vidyanand Kamat

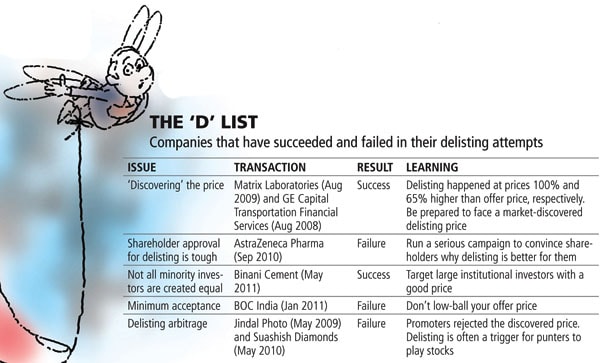

Funds like Kumar’s (that are focussed on India) are today sitting with over $20 billion worth of cash committed by their investors that has yet to be deployed. His solution: Make it simpler for institutional investors, including PEs, to acquire controlling stakes in listed companies and take them private through the delisting route. Current regulatory norms, though simplified, are fairly cumbersome and usually end in a small number of minority investors stalemating the process.

The suggestions are to allow for the “squeezing out” of minority shareholders and the establishment of “benchmark exit price” based on independent valuations and past prices rather than just reverse book building.

PE funds collectively invested over $50 billion into Indian companies between 2005 and 2010. But their investments in listed companies, which stood at a third of all PE investments in India in 2005, have shrunk to 10 percent. This is due to three reasons: High valuations, lack of preferential treatment as investors and unwillingness of the entrepreneurs to cede control. “Today, PE funds have to actively participate in a company’s management to make money, merely investing isn’t enough,” says Harish.

With simpler delisting norms, Kumar says firms like his will “find their own targets” to invest money and privatise. Take Zylog, he says, an excellent mid-market company. It trades at 4-5 times forward earnings but similar companies in the private space will command 10-12 times for the same.

Once away from the pressure of quarterly earnings and regulatory oversight, PE funds claim they can get to work turning around companies. “The focus can shift from quarterly profit numbers to strategic vision of the company and value accretion over the longer run,” says Jacob Mathew, founder of investment banking firm Mape Capital.

But Prithvi Haldea, founder of stock information firm Prime Database, sounds a word of caution. “The reason behind the failure of most delisting attempts was the exit price, either too high for promoters or too low for small investors who saw greater value in holding on to the stock.” That means, any solution would have to be fair to the small investor too.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)