The Untold Story of Jyothy-Henkel Deal

Jyothy Laboratories’ founder M.P. Ramachandran and deputy Ullas Kamath held on for a decade to pocket the failing Indian unit of Germany’s Henkel

This March, Ullas Kamath got news he had been waiting the better part of the past decade for — Germany’s Henkel AG had engaged investment bankers to sell its Indian subsidiary and get out of India, where it had lost money every year since it started operations in 1991.

Not one to waste time, Kamath arrived in Dusseldorf, Henkel’s headquarters, uninvited. Surprising as it may sound, by now the top brass at the world’s third biggest company (after P&G and Unilever) were well acquainted with the company Kamath was associated with: The Rs. 627 crore Jyothy Laboratories. (Founded by middle-class entrepreneur M.P. Ramachandran, Jyothy is better known as the maker of Ujala liquid cloth whiteners and Maxo mosquito repellents.)

Kamath, Jyothy’s deputy managing director and Ramachandran’s right hand man, had met Henkel’s management at Dusseldorf twice in the past 10 years to strike an alliance and had even offered to buy out their Indian subsidiary, but had failed to convince them.

This time, though, he was better prepared. “I was determined to do everything to get the company,” he says.

Over a five-hour meeting, he laid out plans to turn around Henkel’s India business. Henkel, he said, had strong brands, but its management and sales force had failed it. With just one plant in Karaikal, Pondicherry, its logistics costs were out of control. Besides, Henkel India had routinely discounted its brands, which eroded their value.

According to Kamath, and others present, he received a patient hearing with a promise that the company would get back to him. As a listed company, the $22 billion Henkel AG had to follow certain procedures and they could not short-circuit the sale process without inviting bids.

It seemed the matter would have ended there. Yet, less than three months later, and after another trip to Dusseldorf and some negotiation, Kamath walked away with the deal, without entering a bruising bidding war.

How did he pull it off? The clues lie in the entrepreneurial calls that Ramachandran and Kamath made towards the closing of the deal. We’ll come to that in a bit. First, let’s get a handle on how and why the Jyothy-Henkel tie-up was aborted twice in a decade.

The Moorings

There was very little to suggest that the paths of Jyothy Labs and Henkel would cross.

When it started out in India in 1992, Henkel had plenty going for it, with globally well-known brands that were among the top three in the countries it operated in. To help navigate India, it had a reliable joint venture partner in A.C. Muthiah’s Southern Petrochemical Industries Corporation (SPIC), the flagship of M.A. Chidambaram group. For SPIC, the venture worked as forward integration, as its chemicals could be used by Henkel for its products.

Former employees say that the failure of both partners to fully appreciate the challenges in the Indian market plagued the venture from the start. The first major error the company made was to set up a plant in Karaikal to serve the entire country. This was unlike Europe, where Henkel routinely outsourced production. In India, Henkel wasn’t sure of the quality it would get, hence the single plant. The result: Logistics costs were so heavy that they wiped out 10 percent of margins.

Besides, there were several organisational goof-ups. Indian managers had to wait for approval from Germany for minor questions like changing marketing schemes. This made operations slow and lethargic. Also, several employees who came in from SPIC had no background in consumer goods marketing. Most of their experience was in selling fertilisers. Henkel’s parent used this as an excuse to control marketing and advertising campaigns and repeatedly misread the Indian market.

For instance, initial television commercials had models with freckles. A few years later, tanned models were used. “Fair skin is considered a sign of beauty in India and had they just stuck to that [they] would have done much better,” says a former employee.

Perhaps most significant was Henkel’s insistence on building distribution from the ground up. “In retrospect, the company should have tied up with someone. Once the big guys started fighting, we found ourselves squeezed,” says a former employee, referring to Hindustan Unilever and P&G slugging it out over detergents.

On the other hand, Jyothy not only had an eight-year headstart over Henkel India and operated like a local enterprise, Ramachandran, who wears only white, came with a nuanced understanding of the Indian market.

In 1983, Ramachandran didn’t think much of the whiteners in the market and decided to bring out his own formulation. With Rs. 5,000, he set up a small factory to produce Ujala. The product was sold house-to-house by a team of six women. This system of selling resulted in many fertile ideas that helped Jyothy shape its distribution in future. That, coupled with effective advertising and tax planning, allowed the company to grow rapidly.

At Jyothy, all sales staff come from underprivileged families. “We want people who are hungry to succeed,” says Kamath. The only condition is that they must be graduates.

Also, unlike competitors, Ramachandran has ensured that the last point of sale to a shopkeeper is always serviced by a Jyothy salesman. There is also a bar on lateral hiring of sales staff. Jyothy’s 1,800-strong sales force gives it a reach of 1.1 million outlets, making it the highest penetrated product after Hindustan Lever’s Lifebuoy.

From the early days, Ramachandran had a clear belief in the power of advertising. In the pre-detergent war days of the early 1990s, he supported Ujala with huge ad spends, according to Anjan Chatterjee of Situations Advertising, which handles advertising for Jyothy’s brands. In 1997 when the company raked in Rs. 100 crore in sales, it spent Rs. 36 crore on advertising.

Third, Jyothy took effective advantage of tax breaks to set up plants in so-called backward areas. People who know both Ramachandran and Kamath say that this is how they met. Kamath, a chartered accountant in Bangalore, met Ramachandran when a friend went to pitch for a Ujala distributorship in 1990. During the meeting, Kamath suggested Jyothy set up a factory in Pondicherry to take advantage of tax breaks. Since then, all of Jyothy’s factories have been set up in areas that provide tax incentives to businesses.

Ramachandran operated with two maxims: He never relied on debt and ploughed back all his profits into the business. He lived in a 300 sq.ft., one-bedroom house till 1998. Kamath’s tax planning advice proved to be manna from heaven. In three months, he was on the board and became Ramachandran’s most trusted lieutenant.

In 2000, Kamath had first proposed that Henkel and Jyothy combine strengths in distribution to take Henkel products beyond large cities. Henkel demurred. Giving over its distribution network to a company half its size didn’t seem to make much sense.

Then again in 2005, when Henkel India was at Rs. 400 crore in revenues and Jyothy at Rs. 200 crore, Henkel made a similar proposal for a tie-up. Already, the mighty German consumer goods company was beginning to get jittery about its future in India. But here, talks fell apart over one sticky point: Jyothy’s refusal to cede majority control as required by Henkel. “Why should a successful entrepreneur give up his stake?” asks Ramachandran.

But, by the end of the decade, the strength of its distribution network and effective tax planning weren’t enough to drive Jyothy’s bottomline. Profit after tax stayed flat at Rs. 80 crore in 2010-11 on revenue of Rs. 750 crore while earnings before interest tax and depreciation fell by Rs. 5 crore to Rs 107 crore. Margins declined by half a percentage point to 13.3 percent.

With a 58.3 percent volume marketshare in the whiteners segment, Ujala was twice as large as its nearest competitor. Yet, Jyothy was clearly finding it hard to grow its flagship brand without a stronger portfolio of brands.

The time was ripe for yet another attempt by Jyothy to woo Henkel India.

The Coup

When Kamath met the Henkel top brass in Germany, he knew that Jyothy didn’t have the balance sheet size to get into a bidding war. So he did the next best thing: He told Henkel he would get back to India and send them a proposal. He also made it clear he would not participate in a bidding war. And, in what would later turn out to be a masterstroke, Kamath told his German counterparts that even if Henkel chose not to sell to him they were free to use his turnaround plan.

Almost immediately, Kamath got down to preparing a bid. His price: Rs. 24 a share or Rs. 118 crore for the 50.97 percent Henkel AG owned. This was a 40 percent discount to the enterprise value. But the real coup was his decision to take on Henkel’s entire loss of Rs. 450 crore. Kamath figured he could use it to save Rs. 150 crore a year in taxes for the next three years.

Shortly after Kamath sent his proposal, the deal took on a life of its own. A.C. Muthiah, who owned 17 percent in the company — his stake having come down steadily over the years, Henkel AG continued to pay for the losses — was not pleased that the German parent had decided to sell its stake without bothering to consult him.

Through MAPE Advisory Group, he reached out to Kamath and offered to sell him his stake. Kamath knew that this could put him in the drivers’ seat. Once he had a stake in the company, Henkel AG would at least consider his bid. For Rs. 60.73 crore, Jyothy bought Muthiah’s stake, but only 14.9 percent of the company to “not trigger an open offer for the company as we did not want to get into a bidding war.”

Again, Kamath got on the plane to Dusseldorf and made his intent clear. “I’ve bought this stake as Jyothy wants full control of the company,” he recalls telling them. “If you still don’t want to sell to Jyothy, please give me my Rs. 60 crore and take the shares from me.”

When he saw them wavering, he threw in a clause that would seal the deal: If the German parent thought Jyothy had done a good job of the turn-around, they would have the first right of refusal to pick up a 26 percent stake in the Jyothy-Henkel combine in 2016.

The German management caved in. Thereafter, events moved at lightning speed. Jyothy got help from an unexpected source: Kotak Mahindra Bank. By May 5, in less than two months. Jyothy raised Rs. 600 crore and the deal was done. “We felt comfortable making a loan to them at such short notice as we knew they were a debt-averse company and had a healthy balance sheet,” says Paritosh Kashyap, executive vice president at Kotak Mahindra Bank.

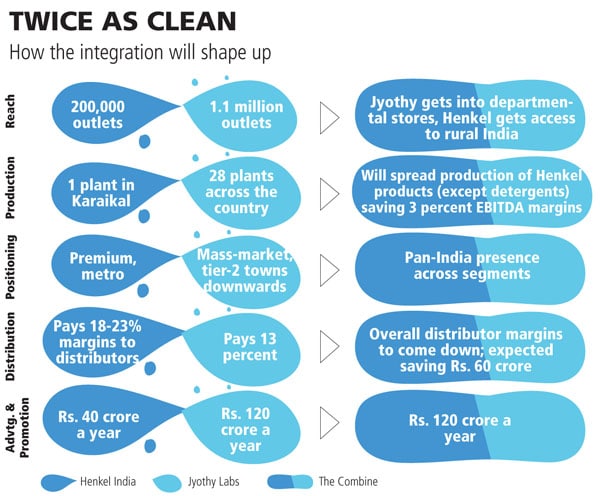

The acquisition has made Jyothy the fourth largest fast-moving consumer goods company in India, with a combined revenue of Rs. 1,100 crore. Now the hard work begins. In integrating the two companies, the Ramachandran-Kamath duo know they have a formidable challenge ahead. This is where they plan to stick to their focus on distribution, advertising and cost savings.

For now, Jyothy has commissioned a 90-day review of all Henkel brands before it fine-tunes its strategy. Ramachandran is confident that the Henkel part of the operation will be able to show profits in nine months. “With growth of its flagship products slowing down, and margins under pressure, this acquisition is the best tax planning Jyothy could have done,” says Subramaniam.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)