Abhay Soi: Health care's new czar

Abhay Soi's Radiant Life Care entered the health care big league after acquiring Max last year. Now Soi has to prove he has the chops to build an institution

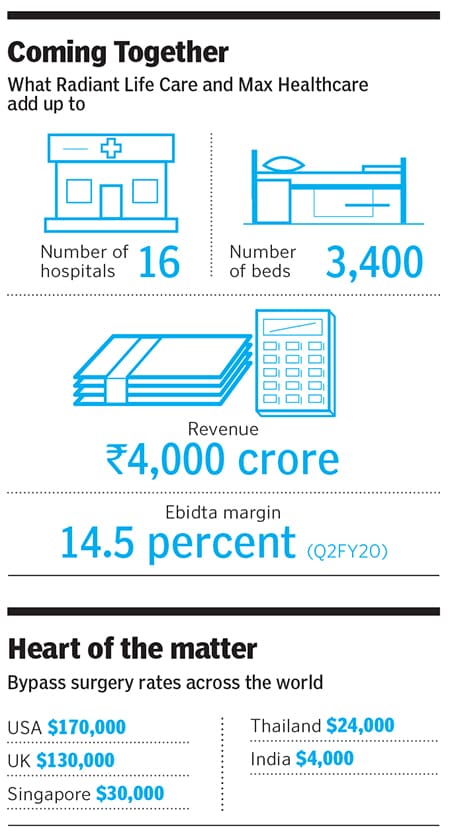

Nine years after starting out in the hospital business, Abhay Soi, chairman, Max Healthcare and Radiant Life Care, has expanded his operations to 3,400 beds and ₹4000 crore in revenue

Nine years after starting out in the hospital business, Abhay Soi, chairman, Max Healthcare and Radiant Life Care, has expanded his operations to 3,400 beds and ₹4000 crore in revenueImage: Madhu Kapparath

In 2010, after spending a decade turning companies around, Abhay Soi, 46, stepped into a business he had no experience in. Spread across five acres and 650 beds, BL Kapoor Hospital in Delhi’s Karol Bagh neighbourhood was on the block. Nine years of constructing this 650,000 sq ft facility had resulted in huge cost overruns. Soi, who in his career had seen spectacular turnarounds as well as dramatic failures, thought he could make a business of it if he got the facility at book value.

Almost overnight, the first-generation entrepreneur raised capital from JP Morgan and his company Radiant Life Care took over operations at the facility. “If it didn’t work out I would have thought of flipping it a couple of years later,” he admits while stating that he knew very little about the hospital business.

Nine years on, Soi has expanded his operations to 3,400 beds and an estimated ₹4,000 crore in revenue. A deal along with partner KKR to buy out Max Healthcare last December from promoters Analjit Singh and South African chain Life Healthcare Group added 10 hospitals to the two he ran with Radiant. It allows him to enter the top league—behind Apollo but ahead of Fortis and Manipal Hospitals.

The Max deal also comes at a time when private equity funds are willing to put in the patient capital that the hospital business in India needs. As opposed to earlier when they were content with taking minority stakes (Apax’s deal with Apollo in 2007 being the most prominent example), private equity funds are now more comfortable doing majority deals as they believe the business has a long way to go in terms of scale and profitability. They see ample opportunity in being able to consolidate single hospitals and regional chains into large hospital groupings.

An often made comparison is with the diagnostics space—Metropolis, Dr Lal Pathlabs, Thyrocare—that has become an investor favourite with valuations quoting north of 50 times compared to the 15 times for listed hospital companies. They hope for some valuation catch-up. Sanjay Nayar of KKR, who has been on the board of Apollo Hospitals and now Max Healthcare, believes there is scope for Ebitda margins to move into the “high teens” from the mid-teens at present. “How that translates into capital market valuations we’ll have to wait and see,” he says. KKR has taken a 51 percent stake in Max Healthcare. Soi, the chairman of the company and responsible for day-to-day operations, has 23.3 percent.

While it is too early to say if Soi, the diffident health care entrepreneur, has arrived, those who have seen him over the years say Radiant has a chance to make it as a large successful pan-Indian hospital chain. “He (Soi) comes from a finance background and understands the unit economics of this business, which is critical to success in any large acquisition,” says Vishal Bali, executive chairman, Asia Healthcare Holdings.

(Left to right) Senior directors are part of the team leading the integration at Max Healthcare

(Left to right) Senior directors are part of the team leading the integration at Max HealthcareImage: Madhu Kapparath

Getting Started

For young and ambitious graduates, the mid-’90s were a heady time in Mumbai. The finance industry, while still small, was tightly knit and corporate restructuring as a practice in India was just making a mark for itself. In 1995, after a BA (pass) degree from St Stephens and an MBA from the European University in Antwerp, Soi stepped into a job at Arthur Andersen working in the restructuring team.

When Arthur Andersen shut shop, he found himself at KPMG and, at 29, ended up quitting without anything in hand. “I told myself that my aim in life cannot be to become a senior partner at a consulting firm,” says Soi who then launched Halcyon Partners, a firm that dealt in restructuring, in 2004. Narayan Seshadri, who was with him at Arthur Andersen, was the other partner.

The only thing they had was a Rolodex of contacts and a few clients—Baroda Rayon and sporting goods maker SSPIL—who agreed to let them work for them in exchange for a small retainer and sweat equity. That way, if the businesses turned around, there was a significant upside in it for Soi.

Some like PI Industries have gone from a ₹40 crore market cap to ₹13,000 crore today. Others like SSIPL, where he was a director until two months ago, also did well. Baroda Rayon flamed out.

Right from his Halcyon days, Soi has never taken personal leverage nor given a personal guarantee on any loan. The one thing he learnt was that restructuring in India requires one to be completely hands-on and roll up one’s sleeves. Dealing with unions, suppliers and the government is hard but extremely rewarding when it pays off. Also that failure could result from factors beyond one’s control.

Halcyon’s big break came when Sid Yog, founder of The Xander Group, an emerging markets investment platform, who had known Soi socially and professionally for over a decade, introduced him to Seth Klarman of Baupost in early 2007. Klarman, a noted value investor, had been looking to invest in turnaround opportunities in India and had approached Xander. Yog declined because he thought it wouldn’t work at scale. “But I knew of someone (Soi) who did this and wasn’t in this space because it was the flavour of the season,” says Yog.

After a few meetings in Boston, Klarman hired Soi to run a sole $350 million mandate on behalf of Baupost in India. Suddenly, Soi had an office and a 20-member staff and a mandate that took care of office costs and gave him a 25 percent share in any gain. Among the investments the firm made were Gayatri Sugars and Anagram Finance. The fund closed in 2009 after the global financial crisis when Baupost, whose special situations fund had grown to $29 billion from $6 billion, decided to consolidate all operations to the US and terminated their relationship with Halcyon. By then, Soi, with 14 years in the restructuring business, was itching for his next opportunity.

The Hospital Business

From the outside, the hospital business had looked like a place where he could put his skills to use. But once Soi acquired BL Kapoor Hospital, his first challenge was to get the right kind of doctors to work for him. “No one wanted to come and work for me. I was an unknown face in the industry and they didn’t know how long I’d last,” says Soi. That’s when he discovered that while big names got headlines, their fees often made it a not-too-profitable proposition. Instead, there were enough doctors working under the bigshots who had a steady stream of patients and were waiting to shift. He started bringing them in.

Usually, specialties like cardiac, orthopaedic, neurology and oncology bring in 50-75 percent of revenue for multi-speciality hospitals. But BLK decided to focus on sub-specialties like organ-specific oncology, bone marrow transplants and organ transplants, which were equally remunerative and had less competition. (When people come in for dengue or other relatively simple ailments, the billing rates are lower and the hospital ends up making far less per bed.)

Third was the focus on medical tourism. Here, Radiant tapped countries in Southeast Asia, the former Soviet states and African countries. Offices were set up as far apart as Myanmar, Kenya and Kazakhstan and patients hand-held through the entire process from visa application, to flights, accommodation for relatives, sightseeing and finally the actual procedure. Softer aspects like having translators on call and food prepared in accordance with their local tastes are also taken care of. An added advantage is that patients flying in for procedures always come for highly remunerative jobs like heart bypass surgeries, knee replacements or liver transplants. A heart bypass that costs $170,000 in the US and $130,000 in UK can be done in India for $4,000. Average revenue per bed for international patients is ₹90,000 a night, twice that of domestic patients. At BL Kapoor, the international patient lounge was particularly busy on a recent visit, with 200 visitors waiting.

To be sure, medical tourism is an opportunity that has been tapped by other hospital chains as well. Soi claims that his hospitals get as much as 30 percent revenue from international patients compared to 15 percent for larger chains like Apollo or Fortis. Either way, he says the opportunity for India is still huge. The National Health Policy estimates the size of the market at $9 billion.

The Max Deal

Through much of 2018, the medical fraternity was focussed on one deal alone: Fortis. While Manipal-TPG was interested, so were the Munjals, Burmans and Malaysian chain IHH. At the same time, Analijit Singh was looking to deleverage his debt levels and reached out to KKR. According to Nayar, Analjit was keen on a steward who would take care of the Max brand and not tarnish his legacy. In Soi, KKR had a willing entrepreneur. A quick due diligence and the deal was done for an equity valuation of ₹4,300 crore with KKR moving from a finance partner to putting in money from a long-term fund.

The deal brings in 10 hospitals and a strong brand but low profitability. Ebitda margins in the first quarter of FY20 were 10.4 percent. Soi’s first task was to work on combining functions. “There are instances where we can now run tests in Delhi-NCR in larger batches and that saves lot of time and cost on equipment,” says Anil Vinayak, senior director and cluster director at Max Healthcare. In addition, they plan to combine overseas medical tourism offices that Max and Radiant run separately.

The biggest savings have so far come from changing systems and processes. With 3,400 beds they can now command the best rates on everything from medicines to equipment. Soi says he has managed to take Max’s Ebitda margins up to 14.5 percent in the second quarter of FY20. While it’s still early days, he’s got a helping hand from Curtis Schroeder, who ran Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok.

The Max acquisition also brought in a successful laboratory business. At ₹460 crore in revenue and 27 laboratories, it has quadrupled in the last four years. It is large enough to be spun off separately, something Soi says he would consider at the right time even as he worries about the increasing regulation in the hospital space. Soi, Nayar and Bali of Asia Healthcare Holdings all agreed that such regulations make it hard to predict what the margin trajectory for the hospital business could be. Measures like serving below poverty line patients for free and the rollout of Ayushman Bharat have the potential to depress margins.

These are all challenges Soi is acutely aware of even as he is on the lookout for more acquisitions. “The challenge we face is so few patients feel they have got value for what they’ve paid,” he says. Globally, margins for hospital companies tend to be in the high teens, something Indian hospital chains haven’t yet gotten to. HCA Healthcare with $48.84 billion in revenue has margins of 19.4 percent and trades at 15 times earnings. For Max Healthcare and Soi, the answer will be clear early next year once the company lists, as he moves from restructuring companies to “building an institution”.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)