Dilip Buildcon reaped rich with wait-and-watch approach

Dilip Buildcon avoided the pitfalls of many infrastructure giants during the UPA-II years by steering clear of toll projects and instead sub-contracting work from larger players. Today its order book eclipses that of former contractors

A visit to Dilip Buildcon’s 15-acre encampment 150 kilometres west of its Bhopal headquarters, reveals the clockwork precision with which the road construction company works. The encampment is a city in itself and, on entering, it becomes clear how mammoth a task road construction is.

There’s a quarry, a stone-crushing plant, workshops for repairing trucks, dumpers, backhoes, excavators, a diesel pump, testing centres to check the quality of materials, temporary offices with biometric readers and a place for 700 workers to stay.

Trucks carrying bitumen, the black material used to pave roads, line up to disgorge their contents into a mixer. The bitumen is mixed with cement and crushed stones at high temperatures to form McAdam (named after Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam who pioneered road construction using the material). It’s a process that goes on all day and night. The site has served as Dilip Buildcon’s base for the last two years. From here, the company has completed Rs 300 crore-worth of road projects.

Road construction is a sector where several companies have distinguished themselves. Since 1999, when the first National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government gave an impetus to the sector with the Golden Quadrilateral project (the highway network connecting Chennai, Kolkata, Delhi and Mumbai) and the four laning of national highways, the business has attracted several worthy players—Larsen & Toubro (L&T), Ashoka Buildcon, J Kumar Infraprojects and Sadbhav Engineering to name a few.

Yet, not all who rushed into the sector prevailed. Some failed to understand the risks associated with the business. As the second term of the subsequent United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government (2009-2014) wore on, the risks came to the fore. Several companies, like Lanco and IRB Infra, realised they had bid too aggressively for toll projects. When traffic numbers failed to materialise, they found their balance sheets stretched. For other projects, payments were delayed and then there were ones where environmental clearances took longer than expected. The result: The UPA-II government came nowhere close to meeting its stated target of constructing 20 kilometres of roads a day. Bad loans, too, piled up and banks became wary of further lending.

Devendra Jain, executive director and CEO, Dilip Buildcon, recalls telling himself around 2005, “All these companies [that are bidding aggressively for toll roads] will be bankrupt in a few years.”

In contrast, Dilip Buildcon steeled itself through those difficult years with a strategy that would prove prescient. Jain, 42, built Dilip Buildcon, in which he has a 31 percent stake, as an engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) company. This meant it would be a sub-contractor for bigger players like L&T. “The company would receive a fixed payment for the roads it built, which included a profit margin. We constructed, got paid and moved on to the next project. There was no risk on our books,” says Jain.

For Dilip Buildcon, which is preparing to list on the bourses this year, the strategy has kept it in good stead. It closed FY2016 with a topline of Rs 4,000 crore. Its annual profit after tax was estimated to be Rs 250 crore in the period, making it one of the largest road building companies in the country.

As road construction picks up pace—recently Nitin Gadkari, Union minister for roads, transport & highways and shipping, announced that construction activity was at an all-time high of 20 kilometres per day—Dilip Buildcon is expected to be a big beneficiary. “In the last year, the pace of construction in the sector has improved. Projects stuck due to environmental clearances are back on track,” says Dilip Suryavanshi, chairman and managing director, Dilip Buildcon.

For as long as he can remember, Suryavanshi, 59, never wanted to work for anyone. His only childhood memory was of his father’s job in the police force. “My father’s was a transferable job; our family was never able to settle in one place,” recalls Suryavanshi.

Soon after completing his civil engineering in 1979, Suryavanshi joined a soya bean extraction factory started by his brother in Bhopal. He was later joined by his two younger siblings. However, a drought in the same year forced the four brothers to look at alternatives and Suryavanshi came up with the idea of a construction company.

In 1988, he ventured on his own and started Dilip Buildcon by undertaking construction of small residential projects, government buildings and petrol pumps. The business gave him healthy returns and also allowed him to see where the next phase of growth was coming from.

It was in 1995 that Suryavanshi hired the then 21-year-old engineer Jain, who was to prove pivotal to the fortunes of the firm. “I realised his [Jain’s] importance and made him a partner with a 31 percent stake in the business,” says Suryavanshi.

As Jain and Suryavanshi went about the construction business, they noticed heightened activity in the road sector. In the early 2000s, when the NDA government decided to tender road contracts, they decided on a model where the developer is paid a fixed fee for construction. At 30-50 kilometres, the road lengths were small and hence involved little risk. Land was usually free of impediments. All a construction firm had to do was move in and construct. The government paid whenever certain milestones were achieved, resulting in little working capital being blocked.

Still, for a small company like Dilip Buildcon, the going was tough. Existing contractors had cartelised the market, making it impossible for a newcomer to enter. Equipment, like trucks and loaders, was rarely available from contractors, who preferred to rent them out to larger companies. Dilip Buildcon was forced to buy its own trucks, dumpers and stone crushers.

With small contracts, Dilip Buildcon forayed into road construction in 2000. Jain narrates a story that is now legend within the company. “On the way back from my wedding, I stopped at Indore to put in a tender for a road project.” Dilip Buildcon won the bid.

Five years later, in a change of policy, the UPA government decided to auction contracts on the basis of projected toll collections. Larger companies lapped up the opportunity. Banks, for their part, were eager to fund these projects. “The capital required for these projects was not something their balance sheet could support. Add to that, the complexity of building a long, say 120 kilometre, road is far higher than building a smaller 30 kilometre stretch,” explains Nikhil Gahrotra, a director at Banyan Tree Finance, which invested Rs 75 crore in Dilip Buildcon for a 9.75 percent stake in 2012.

For Suryavanshi and Jain, not bidding for these projects proved to be a blessing in disguise. “I regularly criss-crossed the country, clocking in excess of 150,000 kilometres a year, and had an idea of how much toll a road could garner,” says Jain. He believed the bids were too aggressive and both banks and road developers would eventually get into trouble.

Jain decided to focus on sub-contracting projects from larger companies for a fee. That way, there was no toll risk on their books. The model worked until about 2012, at which time payments from larger companies started getting delayed. Traffic projections had failed to materialise and the companies couldn’t repay their loans or settle dues with sub-contractors like Dilip Buildcon. The bad loans resulted in a sharp drop in construction and the government rushed to devise a solution.

It decided to eliminate the toll risk and work was contracted on an EPC basis. Dilip Buildcon, which was now sufficiently large, started bidding for these projects. Today, the company has an order book in excess of Rs 1,700 crore, which is larger than that of some companies it was taking work from just five years ago.

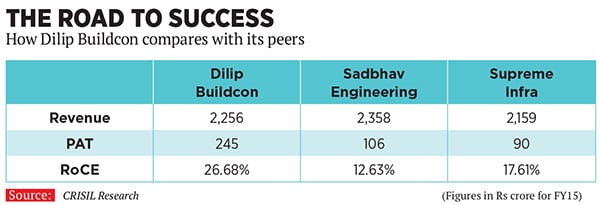

Walk into the Dilip Buildcon office in Bhopal and the success of this model comes to the fore. Across four floors, teams work on what has been billed as the most efficient road construction company in the sector. According to ratings agency Crisil, the company has a return on capital employed (RoCE) of 26.6 percent and a return on equity of 41.73 percent. This is the highest any company has in the business.

Such efficiency can only stem from meticulous planning across all stages of the business, starting with the bidding for projects. A detailed checklist is prepared before placing a project bid. The company looks at how much land has been acquired, whether environmental approvals have been issued, if there are any religious structures or local agitators that could play spoilsport and how proactive the government is. Once the bid is won, the human resources team decides how many workers to allocate for the project. With over 12,000 personnel on its books, the company moves them around efficiently.

They gradually ramp up across each site and ensure that they complete early to claim an early completion bonus from the government. Unlike other road contractors, Dilip Buildcon has invested heavily in buying equipment. The company now has its own fleet of 4,723 vehicles.

It also tied up with equipment maker Caterpillar to buy equipment and recently won an award for being its largest customer. An added advantage: Being able to squeeze discounts and getting preferential rates on annual maintenance contracts. And lastly, as diesel (down by 6 percent in the last year) and bitumen (down by 12-15 percent in the same period) prices have fallen, the company was able to save 8-10 percent on raw material costs last year.

At present, EPC projects make up 80 percent of Dilip Buildcon’s order book. The balance comes from Build, Operate, Transfer (BOT) projects, which are also paid for at a fixed rate by the government, but only once the entire project has been completed and operated for a fixed time period. In the next few years, the company plans to bid for road maintenance contracts that have the potential to contribute a steady income stream.

Dilip Buildcon is also getting its feet wet in other construction areas. The company is working on a Rs 160-crore project for the Bhopal Development Authority to construct lower income group housing, spread across a 40-acre site on the outskirts of the city. In the irrigation business, it plans to build canals and dams and has a Rs 773-crore order book in place. The company says that net margins in this business are around 8-9 percent.

Crisil estimates Rs 24,972-crore worth of national highway projects will be awarded in the next five years with about half being awarded in the EPC space.

For now, the company is well placed to capitalise on the surge in road construction. Its balance sheet has only Rs 2,100 crore in debt, much lower than its peers. (The debt has been taken mainly for BOT projects.) It has no toll risk on its books.

A Rs 430-crore initial public offering (IPO) will allow it to reduce debt further, increase working capital and fund the purchase of new assets. The IPO will also provide an exit route for Banyan Tree. “In 2012, when we invested in a road construction company it was clearly a contrarian call. We’re very pleased with the way this investment has performed,” says Gahrotra.

For now, Dilip Buildcon is silent on the valuation it expects, but it’s safe to say it will be the most expensive in the sector.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)