Escorts: Lord of the field

With Nikhil Nanda behind the wheel, the tractor maker wants to provide holistic agri-solutions, including an Uber for tractors. In the process, it hopes to make farming great again and reclaim its past glory

Nikhil Nanda, MD of Escorts Group, admits to have seen beautiful and tough times over the years

Nikhil Nanda, MD of Escorts Group, admits to have seen beautiful and tough times over the years

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Nikhil Nanda has pretty much seen it all. In his 44 years, the suave and affable millionaire has witnessed his family’s fortunes flourish and then dwindle rather quickly.

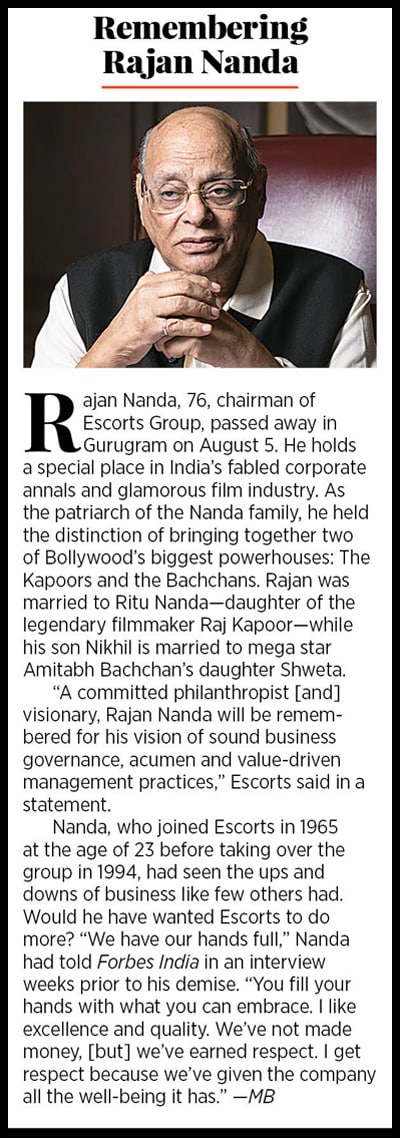

As the son of the late Rajan Nanda, former chairman of Escorts Group who passed away in Gurugram on August 5, Nikhil Nanda was born with the proverbial silver spoon with the group being counted among India’s biggest business houses. Yet, in later years, plagued by the company’s misfortunes, Nanda also felt the sweltering New Delhi heat when the power supply to his office was disconnected over non-payment of dues.

“We have gone through beautiful times as well as tough ones,” says Nanda, now the MD of Escorts Group, sitting in his office in Faridabad, an industrial town on the outskirts of New Delhi. “Today, we have complete clarity about what we are doing. The company has pared its debt from ₹1,200 crore in 2004 to naught after a lot of strategising.”

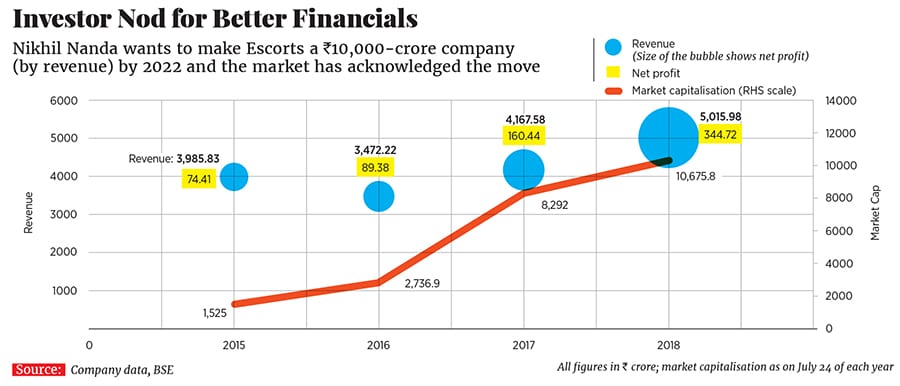

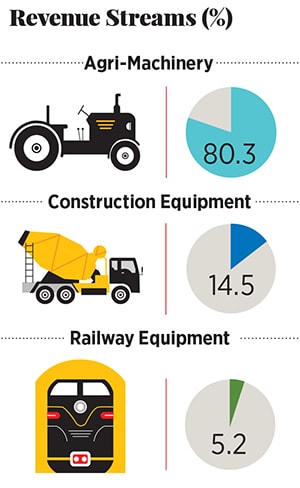

The Escorts Group comprises three engineering divisions. It manufactures tractors and farm equipment under the brands Farmtrac and Powertrac; it has a construction equipment arm and also a railway equipment division. The three units raked in combined revenues of ₹5,015 crore and a profit of ₹344 crore in fiscal 2018. The agri-machinery arm (primarily tractors) accounts for over 80 percent of revenues.

Ambitious by nature, Nanda now wants his company to move up a gear. He plans to make Escorts a ₹10,000-crore company (by revenue) by 2022, a target that he believes can be achieved even earlier. For that, the canny businessman is turning his attention to agriculture, a sector long ignored by the government, but familiar to Nanda. “We want to go from a tractor company to an agriculture one. Earlier, the obsession was to look at a tractor. Now we are looking at crop solutions.” That means, the company will offer implements and know-how to the farmer, spanning the entire agricultural process—from sowing to harvesting.

Nikhil Nanda with his father Rajan (left), who passed away on August 5

Nikhil Nanda with his father Rajan (left), who passed away on August 5 Image: Madhu Kapparath

Already, Escorts is running pilot projects in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, and Nanda says they have helped bring down input costs and improved the quality of output for farmers. “I feel the farmer is still being neglected,” says Nanda. “Eighty-five percent of farmers own below three acres of land. How much can he [a small-scale farmer] grow? Can you justify investments in buying a tractor and other implements? The answer is no. This is what we’ve been challenging our stakeholders with.”

Over the next few years, the company plans to scale up its shared platform, Escorts Crop Solutions, across India. Additionally, it will also offer an Uber-like model for tractors, to make mechanised solutions affordable.

Nanda has chalked out a clear-cut plan. “When Nike started out, it was just a shoe company. Then it evolved into a sporting company. Later it connected the community through health bands, awareness, and other things,” he says, drawing an analogy. “Escorts is on a similar journey. We started with tractors, then we began by offering solutions outside tractors, and now we are offering crop solutions that connect the community. We will change the ecosystem in such a way that the consumer will benefit.”

The third generation scion’s desire to bring about a radical change by altering India’s agricultural landscape runs in his blood. His grandfather Har Prasad Nanda had harboured similar dreams when he arrived in India as a refugee from Pakistan seven decades ago.

From Lahore to Delhi

Escorts traces its beginnings to the time of India’s Independence. Then, Har Prasad Nanda and his brother Yudi were running a successful bus service business in Lahore, in present day Pakistan. But, as Partition happened, the siblings fled to India.

Despite having only ₹5,000 in his pocket and two cars, Har Prasad chose to stay at a suite in the swanky Imperial Hotel in New Delhi instead of living with his relatives. The Imperial Hotel was then the most expensive in the city and the rationale behind the move was that a young Har Prasad could revive his business contacts.

The ploy worked, and by 1948, Har Prasad had established Escorts Agricultural Machines Ltd to market tractors and farm implements, before going on to become a leader in the Indian tractor market with franchises of the US-based companies Massey Ferguson and Minneapolis-Moline. For an agrarian economy that had only recently become independent, tractors were indispensable. “This company started as an agency house and its promoters were good with people,” Rajan Nanda told Forbes India in an interview a few weeks before his demise. “They made political relationships and all the decision making and capital making was political, not commercial. They got well connected and started the business.”

By 1959, the company also collaborated with German automotive parts maker Mahle to manufacture pistons, eventually becoming India’s largest producer of piston assemblies.

But, the spirited Har Prasad was hungry for more. He formed a joint venture (JV) with Ford Motor Co to manufacture Ford tractors in India. The JV went on to become India’s largest tractor manufacturer and by 1984, Escorts had also inked a deal with Japan’s Yamaha Motor Company to manufacture motorcycles. In 1998, the company ventured into health care, setting up the Escorts Super Specialty Cardiac Care Hospital in New Delhi, a landmark medical facility in the national capital.

Thus, by 1991, when India decided to open up its economy, Escorts was in full bloom. Around the same time, by 1994, Har Prasad handed over the baton of Escorts to his son, Rajan Nanda.

With the New Economic Policy in place, many regulations were relaxed and multinationals found little use for local partners. That meant, Escorts, under the leadership of Rajan Nanda, was staring at difficult times, as many of its partners began nurturing independent dreams. The company’s partnership with Yamaha was the first to be called off, and then a construction equipment JV with JCB was also terminated in 2003. Meanwhile, Ford sold its tractor business to New Holland Agriculture, which had its own plans for India.

Plagued by the sudden turn of events, yet raring for more, Escorts dabbled in telecom—launching the Escotel brand in 1996 (later sold to Idea Cellular in 2004)—and continued with health care with the Escorts Heart Institute before exiting that in 2005.

“We are a part of India, and India has gone through a change,” says Nikhil Nanda. “Escorts was present in a lot of businesses. But, it is the survival of the fittest. Between 2002 and 2007, we took strategic calls to exit a lot of businesses that weren’t giving any returns.”

Road to recovery

Today, Escorts is a shadow of its former self, but is rapidly laying the groundwork to reclaim its lost glory. Much of that began with the changes Nikhil Nanda and his team made in 2011. Nanda had been joint MD of the company since 2007, and assumed full leadership in 2013. By then, the company had also halved its debt, thanks to its sale of assets.

“The resurrection came after 2011 when we initiated new products, and cost and quality control,” recalls Nanda. “Once the balance sheet got corrected, there was clarity. We did a lot of internal corrections. We had to think frugally in a linear fashion. We took bold decisions to consolidate businesses. But most importantly, we became clear about what we wanted to do.”

That clarity translated into introducing improved and efficient Farmtrac and Powertrac range of tractors in an attempt to catch up with competitors. “Our consumers were upset during our lowest period because we weren’t able to deliver what we should have been delivering, but they were forgiving which makes us feel blessed,” says Nanda.

With the government’s renewed focus on agriculture—through measures such as the plan to double farmers’ income by 2022—tractor sales are most likely to move north. What has helped is that the acreage under irrigation has improved significantly

in the last few decades. Rating firm ICRA expects tractor sales in India to grow by 7-9 percent in the current fiscal.

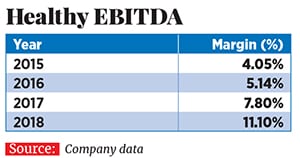

“A year ago, we were discussing our annual operating plan and saying that while we are growing by numbers, the Ebitda growth is only between 0.2 percent and 0.3 percent,” says Shailendra Agrawal, chief operating officer and head of R&D at Escorts. “We decided we should take that to 5 percent.”

To do that, the company has been preparing a blueprint to increase its distribution network, targeting a 4 percent growth in market share in three years, by improving manpower productivity and a renewed focus on R&D. It helps that Escorts has managed to see a spectacular growth in fortunes in the past four years. The company’s revenues have almost doubled, while profits have grown nearly five times. Investors, too, have taken note. Market capitalisation—which has grown seven-fold in the past four years—is at an all-time high.

Electric tractors, Tracxi and crop solutions

Now, as Escorts enters its next phase of growth, Nanda is clear about his priorities. “In the total eight years of turnaround, taking in oxygen was our first obsession,” says Nanda. “That meant making a profit, and reaching the benchmark to go beyond.” Over the next few years, apart from growing sales, the company has also lined up a slew of measures as it turns itself into a holistic agricultural solutions provider.

Under its pilot projects in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, Escorts is undertaking all the necessary work needed for a farmer on a pay-as-you-use basis. The company charges anywhere above ₹700 to provide mechanisation solutions with state-of-the-art equipment required across various stages of cultivation, including ploughing and harvesting.

“So if you’re a farmer, I’ll sell a service to you instead of selling a product,” says Nanda. “If you grow rice, I’ll offer to do all the seven processes required to grow rice, starting from land, laser levelling and seeding to harvesting and beyond, providing the best equipment and technology.”

While the idea isn’t entirely novel—wealthy farmers offer the same to marginal farmers—experts see a huge potential in shared agri-machinery. “Farmers in India have been primarily engaged in manual labour for long,” says Nitin Puri, global head for food and agri advisory at Yes Bank. “The concept of pay-per-hour and pay-per-acre has been underway in an unorganised manner. But, there are no companies providing comprehensive solutions. That could be a huge opportunity for Escorts because it is also a chance to create allied businesses such as insurance for farmers, when you have such a large number of them using your service.”

With just 20 percent of the country’s farmers using mechanised tools, analysts are also upbeat about Escorts’ Traxi—an Uber-like model where farmers can hire tractors on a rental basis from the company or other farmers. “This is perhaps the best way forward,” says Arvind Singhal, chairman of New Delhi-based consultancy firm Technopak Advisors. “Shared solutions play a crucial role and they will help bring in a larger pool of users into the process. That’s a huge business opportunity, but not an easy one to undertake.”

The difficulty, Singhal reckons, is partly due to the challenges that come while bringing in fundamental changes to the way a company functions. “It’s not easy to go from being a product-specific company to a service-oriented one. That means reinventing its thinking altogether,” Singhal says. “That could be a challenge.”

Meanwhile, Nanda has on his drawing board plans that could fundamentally make farming greener. In a country where pollution is a major concern, and rising fuel prices only add to the woes, the company launched India’s first electric and hydrostatic engine transmission tractor under the flagship New Escorts Tractor Series last year. The commercial production of the tractor is expected to begin this year.

“We are looking at two templates,” Nanda says. “What we can do on the technology side and how we can fundamentally change the cost of ownership. That means making the tractor smarter and giving brains to metal. All of these and more such services will truly change Escorts from being an equipment provider to an ecosystem provider.”

Perhaps, the days of glory are just around the corner, once again.