Mohan Lakhamraju: The accidental academic

A PhD dropout and former head of Tiger Global's India operations, he is today an education baron with the Great Lakes Institute of Management and Great Learning

Lakhamraju is targeting modern professionals who pursue multiple careers, unlike earlier ones with only one

Lakhamraju is targeting modern professionals who pursue multiple careers, unlike earlier ones with only one

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Mohan Lakhamraju never aspired to be a teacher. That’s precisely why the 41-year-old quit midway while pursuing his PhD in computer science at University of California, to begin an entrepreneurial journey in 1999. “I never wanted to be an academic,” he tells Forbes India. “I have always been an action junkie.”

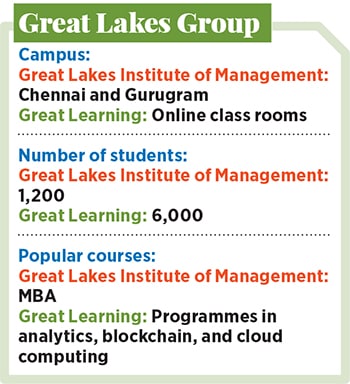

Call it a twist of fate or irony, two decades later, Lakhamraju has emerged as one of India’s most promising educationists, running two management schools and one of India’s largest e-learning firms. A former venture capitalist (VC), he is the vice chairman of the Great Lakes Institute of Management, currently India’s 16th best management school according to the education ministry, and the CEO of Gurugram-based Great Learning, an online classroom programme for working professionals.

“I have always believed good education changes you,” says Lakhamraju. “I came from a middle-class family; it was my education that helped me shape who I am today. Hence, the focus on education.”

Lakhamraju, who set up and headed marquee private equity firm Tiger Global’s India operation between 2007 and 2009 before starting out on his own, has over 7,000 students studying various programmes across both his institutes today.

The Great Lakes Institute of management has two campuses, one in Gurugram and the other in Chennai while Great Learning has six facilities spread across Chennai, Bengaluru, Gurugram, Pune, Mumbai, and Hyderabad. The group is currently in the midst of setting up a university in Chennai, where it will impart both online and classroom education in addition to undergraduate programmes.

“Today, higher education is on the cusp of change,” says Lakhamraju. “Earlier, one would complete their higher education and go through life in one career. That is changing. Now they pursue four or five careers, and that means four or five significant interventions. That’s where we are focusing on.”

Hyderabad to Silicon Valley

Born and brought up in Hyderabad, Lakhamraju graduated with a degree in computer science from IIT-Bombay in 1998. “Computers weren’t that common then,” he says. Immediately after graduation, he received a fellowship to the University of Berkeley to pursue his masters and a PhD in computer science. “Until then, the plan was laid out for me,” Lakhamraju says. “But dropping out of PhD was my first independent career decision.”

However, before he quit, he had already started working on Stratify, a SoftBank-backed software technology startup. It was eventually bought out by Hewlett Packard. “I actually wanted to be an entrepreneur,” says Lakhamraju. “I saw myself as someone who got things done and with that realisation, I dropped out and started working with serial entrepreneurs.”

While at Stratify, Lakhamraju also understood the need for business education to help understand the nuances of the trade. In 2003, he enrolled for an MBA from Stanford University. “I knew about my shortcomings and that was the motivation to go back to business school,” says Lakhamraju. Stanford led Lakhamraju to VC firm Draper Fisher Jurvetson and eventually to Tiger Global in 2005.

“In 2005, very few people looked at India [in terms of investing],” Lakhamraju says. “Tiger wanted to find someone to do that. It was a broad mandate and included public markets and late-stage private equity across sectors.”

Lakhamraju was the chosen one; he moved to the country to set up Tiger Global’s India office in Mumbai and led its investments there for the next few years.

With a $1-billion fund to look after, he held a firm grip on the Indian markets, but the global economic crisis of 2008 played spoilsport. With funds drying up, he decided it was time to venture out and start something that wouldn’t be hit by macroeconomic situations, like the financial sector. He zeroed in on education.

“It was also a time when the supply in education overshot demand,” explains Lakhamraju. “Before that, it was always a supply constraint. Once supply overshoots demand, quality starts becoming important. Given my background, I felt I had an opportunity to scale up quality education. Until then, the belief was that supply and quality wouldn’t go hand in hand.”

The Great Lakes Institute of Management in Chennai

The Great Lakes Institute of Management in Chennai Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes India

Successor to Bala

Lakhamraju’s initial plan was to set up a business that would focus on the entire paradigm of education, from kindergarten to postgraduate studies. However, the massive investments needed in the K-12 category forced him to rethink his strategy.

“In K-12, the focus is always on infrastructure, land and money,” Lakhamraju says. “In K-12, it also takes a long time for results to show. We wanted to do something that could have an [immediate] impact. We also didn’t have all the money to set up the infrastructure.”

With a leased-out 12,000 sq ft building in Gurugram, Lakhamraju set up the Institute of Energy Management and Research in 2009. It did not have a playground or cafeteria, he recalls. “We started with a programme on the energy sector,” he continues. “The focus was on quality, technology and people.” With 30 students and a fee of ₹8 lakh for two years, Lakhamraju reckons that the programme was highly successful and claims many of its students have climbed to the ranks of country heads for their respective organisations. “By the time the first batch graduated, we were among the top 20 colleges in terms of compensation,” Lakhamraju claims.

That year, Lakhamraju also invested in the Chennai-based Great Lakes Institute of Management, where he took on the mantle of vice chairman and CEO. The institute, founded by Kellogg School of Management professor Bala V Balachandran, had already established itself as a premier business school in the country. “He was looking for someone to partner with,” says Lakhamraju. “I had realised the power of brand in education because it helps to grow. That’s when we decided to partner.”

The Institute of Energy Management and Research eventually merged with Great Lakes and became the Great Lakes Institute of Management. Since then, Lakhamraju claims Great Lakes has grown by eight times in eight years. “It was ranked around 33; now we are in the top 10 in most surveys,” he says. The government’s National Institutional Ranking Framework ranks the institute at 16 out of 50, even ahead of SP Jain Institute of Management and Symbiosis Institute of Management. The two campuses have a total of over 1,200 students.

“We don’t have the alumni base of CEOs,” Lakhamraju says. “But what we have is the ability to innovate. We introduced a programme in analytics. We started programmes in artificial intelligence and machine learning because they will become a part of future.”

With Great Lakes firmly in the driver’s seat, Lakhamraju entered into another booming segment: Online education. In 2013, he launched Great Learning, an online and hybrid learning company, that provides postgraduate programmes for working professionals.

“The founder of Coursera [Andrew Ng] was my PhD classmate,” says Lakhamraju. “Whenever we met, he spoke about the traction Coursera was getting.”

Subsequently, Lakhamraju and his team began researching on online educational platforms and the outcomes they provided. Immediately after, Great Learning began offering a postgraduate programme in business analytics and later on machine learning, cloud computing and an executive MBA. In its first year, it had 30 students, a number that grew by 90 in 2014. Today, Great Learning claims to have over 6,000 students annually.

The company offers three models of education. The first, a blended model, allows for 50 percent classroom learning while the rest is online. Students have to attend classrooms one weekend every month. “Our analytics programme is the largest analytics programme for working professionals in India,” claims Lakhamraju. “Within six months of completion, they get a pay hike of 50 percent and have managed a transition into analytics jobs.”

The second is an entirely online model where the students work in a team of five, with a dedicated mentor. “We can replicate the rigour of classrooms by using personalised mentorship,” says Lakhamraju. The third model is a boot camp where students can complete the programme between three and four months. The classes are held at Great Learning’s centres across metros. “The classes are full time and meant for youngsters. “By doing that, we are bridging the gap in what colleges teach and what the industry wants,” Lakhamraju says.

Lakhamraju has also set up a team to prepare the syllabus for programmes. “We are engaged with industry experts and academics,” he says. “When we hear there is a need, based on our research, we put together the curriculum. Currently, the most in-demand fields include analytics, blockchain, and cloud computing.”

Experts agree that Lakhamraju’s model, offering both brick-and-mortar, and online classrooms will reap rich dividends in future. “The Indian economy is changing at breakneck speed,” says Aurobindo Saxena, who heads education practice at consultancy firm Technopak. “The focus is on job-oriented courses as companies have not been finding the right talent. Institutes such as Great Learning enjoy the flexibility of creating programmes meant for the job market.” Saxena reckons that the Indian education industry contributes about 7.5 percent to India’s GDP, roughly translating to a $14-billion industry. “Of this, the online certification industry is about $200 million and is growing between 25 percent and 30 percent annually,” Saxena says.

That’s a huge market to capture where players such as Simplilearn, Udacity and GreyCampus have been trying to gain a foothold. It also helps that India is in the midst of an internet boom, led by smartphones. Asia’s third-largest economy is expected to have over 530 million smartphone users by 2018, a number that is expected to go up to 830 million by 2021.

“The future is going to be technology-oriented,” says Narayan Ramaswamy, partner and head of education practice at KPMG. “Unlike before, devices and internet have become easily accessible. That means the future is looking bright for companies such as Great Learning. The early adopters of the technology are the ones who will reap the benefits in the future.”

With his entire business bootstrapped, it is only a matter of time before investors flock to Lakhamraju to grab a pie of his business. But the PhD dropout is clear about his goals. “We want to transform the way education is in India,” Lakhamraju says. “We want education to have an impact because I have benefitted from quality education.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)