Pepper Tiger: How Synthite Group hits the right notes with its spices

Respecting the family charter, valuing a risk-and-reward approach and adding a fair share of professionals have made the 40-year-old Synthite Group roar in the world of spices and oleoresins

(From left, standing) Rishal Mathew (DGM purchase, Synthite), Jacob Issac (business development manager, Synthite), Ashok Mani (MD & CEO, Intergrow Brands), Paolo George (deputy MD, Symega Food Ingredients), Jacob Ninan (MD, Herbal Isolates), John Joshy (GM, sales and marketing, Synthite), Joseph John (CEO, Synthite Infrastructure). (From left, seated) Varghese Jacob (MD, Synthite) Aju Jacob (Joint MD, Synthite) Image: Arun Chandra Bose for Forbes India

(From left, standing) Rishal Mathew (DGM purchase, Synthite), Jacob Issac (business development manager, Synthite), Ashok Mani (MD & CEO, Intergrow Brands), Paolo George (deputy MD, Symega Food Ingredients), Jacob Ninan (MD, Herbal Isolates), John Joshy (GM, sales and marketing, Synthite), Joseph John (CEO, Synthite Infrastructure). (From left, seated) Varghese Jacob (MD, Synthite) Aju Jacob (Joint MD, Synthite) Image: Arun Chandra Bose for Forbes India

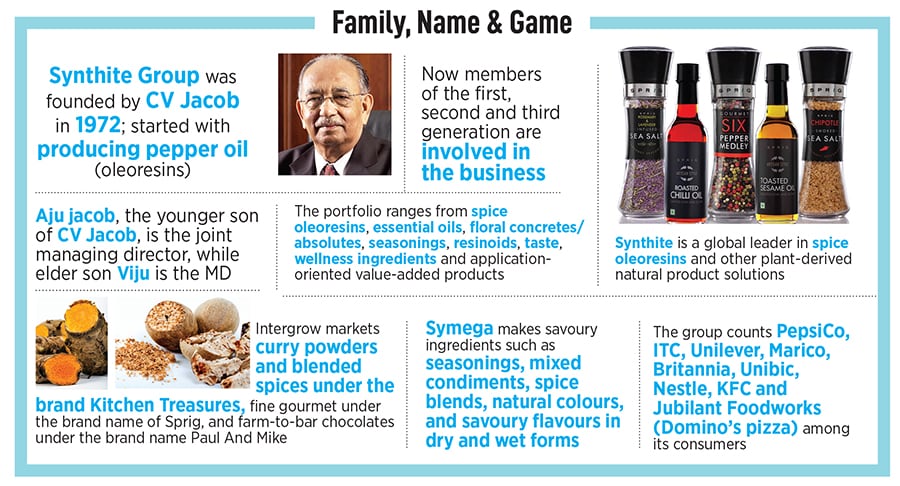

Aju Jacob starts the conversation by giving a simplified lowdown on the flavour of his family business. “If you crush black pepper in your hands, you get an aroma,” explains the chemical engineer who joined Synthite Industries in 1987, a year after graduating. His father, CV Jacob, started Synthite in 1972 by extracting oil and resin from spices such as pepper. The aroma is due to the evaporation of the volatile essential oil, which is derived by crushing pepper. “It’s aromatic and has a slightly musty odour,” says the 57-year-old joint managing director of Synthite Group, who has spent over three-and-a-half decades in the business.

Once the oil has been extracted, Aju continues, one can get resin as well. “Oil gives you aroma, and resin gives you taste. You combine both, and it’s oleoresin,” underlines Aju, adding that Synthite Group is India’s largest producer and exporter of spice oils and oleoresins. “You take the same pepper and bite it, you get pungency,” he smiles, highlighting a more caustic aspect of the business of spices.

The second generation entrepreneur, for sure, was enjoying the heady aroma of the family business. In 1987, Aju was 22, Synthite had a turnover of ₹6 crore and was processing around 300 tonnes of chillies a year, and the founder had diligently built up a sizeable export empire that included outposts like the US. Aju spent the first two years on the shop floor learning the essential ingredients of production and the business. Towards the end of 1988, he went on his first overseas business trip to Europe for about seven weeks. “That was a great experience and exposure,” he recounts. The young lad, for sure, had quickly developed a taste for spices.

Four years later, in 1992, Aju discovered another facet of spices: Pungency. Spain, which till the late 1980s was the paprika capital of the world, was losing its competitive edge and India was fast filling the gap for the spice made from dried and ground red peppers. Synthite, which was at the forefront of making the most of the global opportunity, was struggling to meet a sudden spike in burgeoning demand. Aju rented a factory which had its share of labour issues and was locked down.

Four years later, in 1992, Aju discovered another facet of spices: Pungency. Spain, which till the late 1980s was the paprika capital of the world, was losing its competitive edge and India was fast filling the gap for the spice made from dried and ground red peppers. Synthite, which was at the forefront of making the most of the global opportunity, was struggling to meet a sudden spike in burgeoning demand. Aju rented a factory which had its share of labour issues and was locked down.

The young entrepreneur resolved the issues, opened the plant and started production. All went well for six months. After that the owner of the factory went bankrupt, and Aju decided to buy it. So far, Synthite had been processing only one product at the plant. After acquisition, Aju reasoned, the plant could be beefed up to function as a multi-product factory. Though the move made sense, it was a risky bet by the young entrepreneur who was trying to find a place for himself in the family hierarchy.