Santoor: Stay regional and gun for No.1

How Wipro's Santoor became a ₹2,000-crore soap brand—and India's second largest—by ruling just four states

Vineet Agrawal, CEO, Wipro Consumer Care, sings paeans to the virtues of staying regional

Vineet Agrawal, CEO, Wipro Consumer Care, sings paeans to the virtues of staying regionalImage: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Vineet Agrawal loves to tell the Santoor story in four parts. The first part begins in the mid-’80s, when Agrawal joined the sales and marketing team of Wipro Consumer Care, the FMCG arm of IT services giant Wipro, which traces its roots to Western India Vegetable Products Company, an edible oils and soaps maker since 1945.

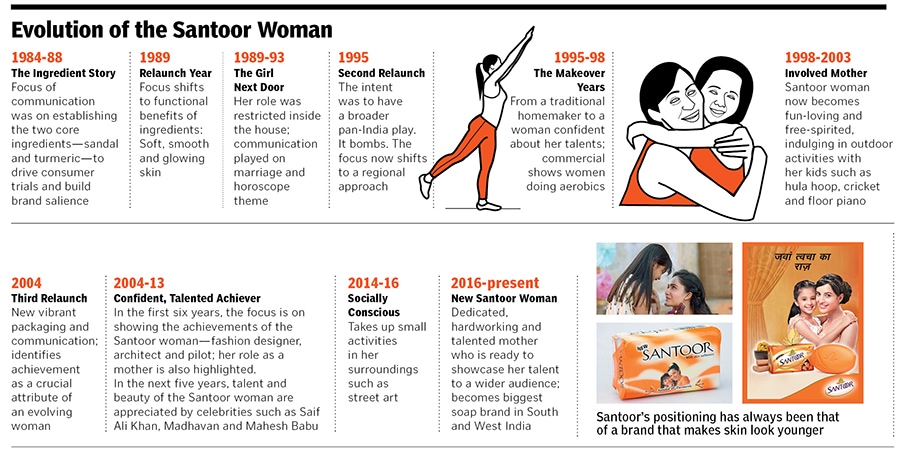

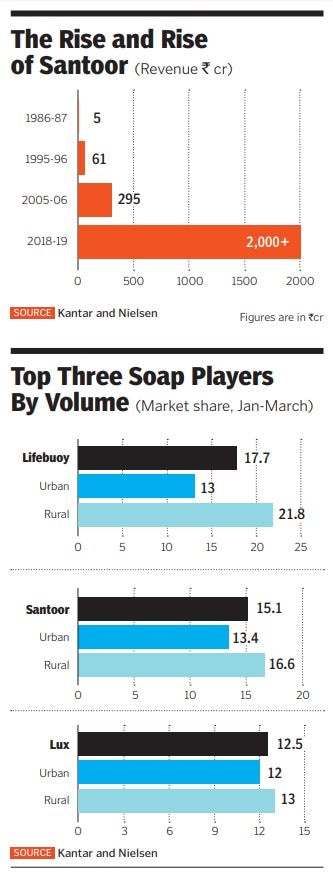

Launched in 1984, soap brand Santoor had a sedate beginning, with revenues plodding to ₹60 crore in little over a decade. Though the growth was modest, the stakeholders had nursed a far more ambitious plan. The intent was to expand the footprint across India.

Santoor was relaunched in 1995 with much fanfare. The packaging was changed, and the shape of the sandalwood- and turmeric-loaded soap was tweaked to make it look more contemporary. The idea was to fight brand fatigue as well as make it more enticing. The launch flopped. “Nothing happened. Numbers (sales) didn’t move,” rues Agrawal. Wipro was forced to go back to the drawing board.

The second part of the story is that of the competition. Owned by multinational Goliath Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL), Rexona, Lux and Hamam were ruling the roost across the country. Led by incumbent Rexona, the trio had left little space for rivals. While Rexona and Hamam were big in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, respectively, Lux was dominant in North India. Santoor, in contrast, was languishing at a distant No. 4, at times even a tad lower, in the pecking order. The vision to be seen everywhere had resulted in Santoor spreading itself too thin.

Now for the third part: The reality check for Wipro. The ambition of becoming a pan-India player was buried unceremoniously and the brand custodians decided to narrow Santoor’s focus to the four states in South and West India where it was doing reasonably well: Andhra, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat.

“You cannot under-invest and win,” says Agrawal, now CEO of Wipro Consumer Care and Lighting, which closed the year ended March 2019 with a top line of ₹7,100 crore. The brand, recounts Agrawal, pulled out all money from the North and East, and pushed aggressively into the West and South.

Result? David pipped Goliath to become the second-biggest soap brand in India in value, and third largest in volume. In the year ended March 2019, Santoor posted ₹2,065 crore in revenue, taking it close to the leader Lifebuoy, reportedly worth over ₹2000 crore. Lux, reportedly in the ₹1,000 crore club, is third biggest in volume and second in value. HUL chose to put its might behind its Lifebuoy and Lux, which meant that Rexona and Hamam are no more the forces they once were.

Santoor, reckon brand experts, is a silent journey. “The brand relies more on the solidity of its product than anything else,” says Harish Bijoor, founder of his eponymous branding consultancy firm. The brand, he adds, has understood early in its life that there is a user and a buyer. In the case of Santoor, the user is the buyer, and also a big influencer in the home as to who will use what. In the case of Santoor, the buyer, user and influencer are all packaged into the avatar of the young mom in the house, adds Bijoor.

Stay regional and gun for No. 1 may well be the mantra for Agrawal. “In Andhra (and Telangana), we are almost four times the second brand,” asserts Agrawal, who now sings paeans to the virtues of staying regional. In FMCG, he underlines, there are a lot of brands that are not national, but the owners force them to become so. It’s an avoidable sin.

The war-weary CEO dishes out a China example, where a number of regions are as big as many national markets. Take, for instance, the Guangzhou Province in South China. A population of over 10 crore and a GDP of $1 trillion make the region much larger than Malaysia or the Philippines. Back home, when Santoor was tagged as a ‘southern brand,’ Agrawal stayed unflustered. Reason: You can get size and economies of scale even as a regional brand.

Decoding Santoor’s soap opera, however, remains incomplete unless one gets to knows what ‘really happened’—the last part of the story.

In the early ’90s, North and East India accounted for just 10 percent of sales. “We decided to lose 10 percent to make the most of the 90 percent in the South and West,” Agrawal recounts. “The new theory was that in the four states people should see us more on TV than any other brand,” recalls Agrawal. Distribution reach, especially rural, was beefed up, retailers were wooed with incentives and smaller shops were targeted.

The aggression was not confined to television. For two months in a year, a bunch of cities were turned ‘orange’. Since the packaging and product were orange, thousands of shops were painted orange, and hoardings and banners—all orange—were plastered across the towns and cities. Suddenly, Santoor was all over the place.

Places shortlisted for the marketing blitzkrieg were an eye-opener. The top cities were shunned. “It was not Hyderabad or Visakhapatnam, but places like Warangal, Vijaywada, Nellore and Guntur where activations took place,” says Agrawal. The traditional centres were cluttered, penetration into smaller towns was easier, and it helped in staying away from the gaze of the rivals. “The competition didn’t notice us,” he says with a grin.

The Santoor makers had a plan on which brand to take on first: Rexona.

While others such as Lux talked about how soaps enhanced the beauty quotient—read face value—of the users, Rexona was the only one apart from Santoor to talk about the beauty of skin. “We also felt that Rexona was probably the weaker brand (in HUL’s portfolio) to attack,” he adds.

Towards the fag end of the ’90s, HUL rebranded Rexona as Lux Rexona. The new identity created confusion among consumers and traders as Rexona’s skin proposition got muddled with the cosmetic beauty of Lux. “It was a golden opportunity for us,” recalls Agrawal, who sharpened the attack on Rexona and positioned Santoor as the only brand that makes skin look younger. After two years, HUL dumped the Lux Rexona branding, leaving Rexona to its original solo existence.

Santoor, on its part, stuck to its positioning: The woman who uses the soap, a mother, is mistaken for a younger woman.

Santoor, avers brand strategists, worked on a more sustainable thought: Women desire timeless beauty. A married woman, with a child, who still looks like a college student is far more realistic in portrayal than other soap brands that harp on fairness and cosmetic beauty. “Santoor was the promise of timelessness for the everyday woman,” says Abhik Choudhury, founder of Salt and Paper, a brand consultancy. The message conveyed was simple: Don’t become Sridevi overnight, but feel the best version of yourself preserved over the years.

Although entering the coveted ₹2,000 crore club is remarkable, Santoor is likely to face headwinds as it expands its reach. Maintaining a similar growth rate will definitely be a challenge as the headroom for growth in its current dominant markets is not too high. “This could see the brand lose steam,” avers N Chandramouli, chief executive officer of TRA Research. Making successful Santoor product extensions is also going to be challenging, as it has been for many other bath soap brands.

Another challenge is converting the younger audience. While Santoor’s ever-loyal customers are mostly middle-aged women, college youth and young working professionals have almost nil brand loyalty. “They might lose their foothold if they don’t crack this code,” says Choudhury.

Agrawal can sense what’s coming. Even if somebody attacks us in any of our four big states, he stresses, the brand is geared to fight. “We won’t cede an inch.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)