Dabur vs Patanjali: Veda wars

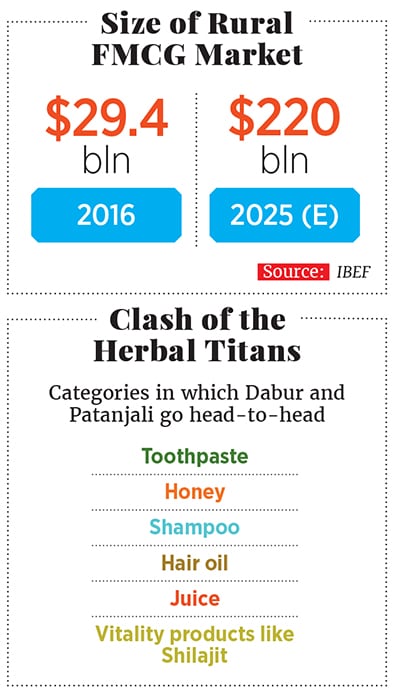

After surviving the Patanjali storm in the cities, Dabur dons an aggressive avatar to defend its rural turf. It's a battle between ayurveda based on science versus healing hinged on faith

(Left) Amit Burman Vice Chairman, Dabur and Sunil Duggal, CEO, Dabur India

(Left) Amit Burman Vice Chairman, Dabur and Sunil Duggal, CEO, Dabur IndiaImage: Madhu Kapparath

It took Dabur five quarters—a good 15 months—to realise that ayurveda hinged on ‘faith’ was getting the better of the one based on ‘science’. Patanjali, an ayurvedic upstart backed by maverick yoga guru Ramdev, had disrupted the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market in early 2015. The bunch that first felt the heat were the multinational giants (MNCs) led by Hindustan Unilever and Colgate, who were vilified by Ramdev as a ‘foreign evil’ exploiting the country.

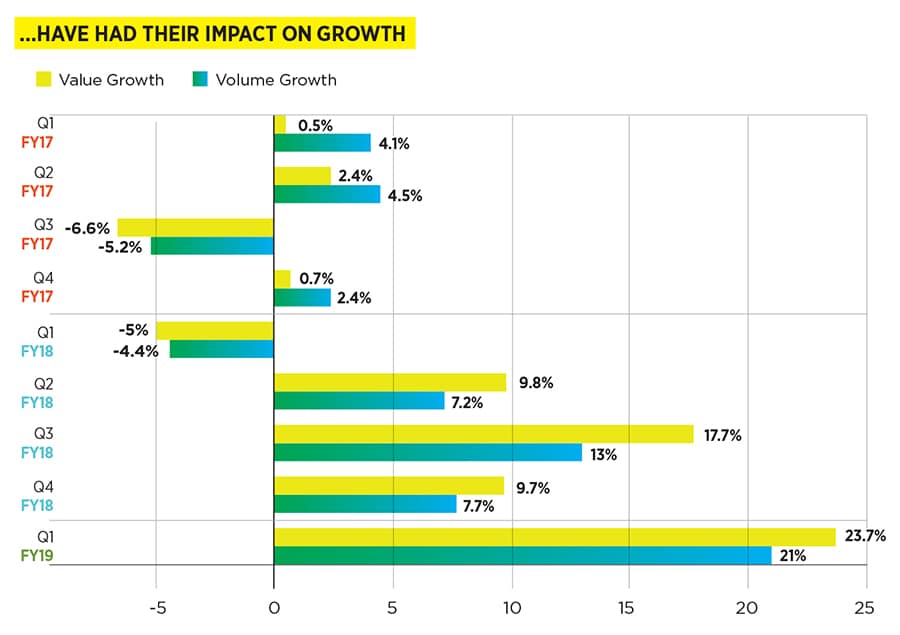

For Dabur, the fifth-largest FMCG company by revenue in India, the first vestige of a threat was in branded honey, a relatively small (worth ₹1,100 crore) category but core to the Dabur portfolio. In a first in over two decades, sales dipped by 8.50 percent in the first quarter of 2017 fiscal over the previous year’s corresponding period. For a company used to robust double digit sales growth in this category, the decline came as a bolt from the blue.

“Our competitor was selling honey at a price 30-40 percent lower than ours,” recalls Sunil Duggal, a Dabur veteran who took over as CEO in 2002. “We erred in our thinking that these disruptive forces were of short duration.”

For the next four quarters, honey sales kept sliding, slowly but surely eroding Dabur’s dominant market share of 60 percent; it reached a new low of 40 percent. To make matters worse, the volume market share of Dabur’s flagship Chyawanprash brand also fell by almost 2 percent—from 58.9 percent in October-November 2015 to 57 percent during the same period in 2016.

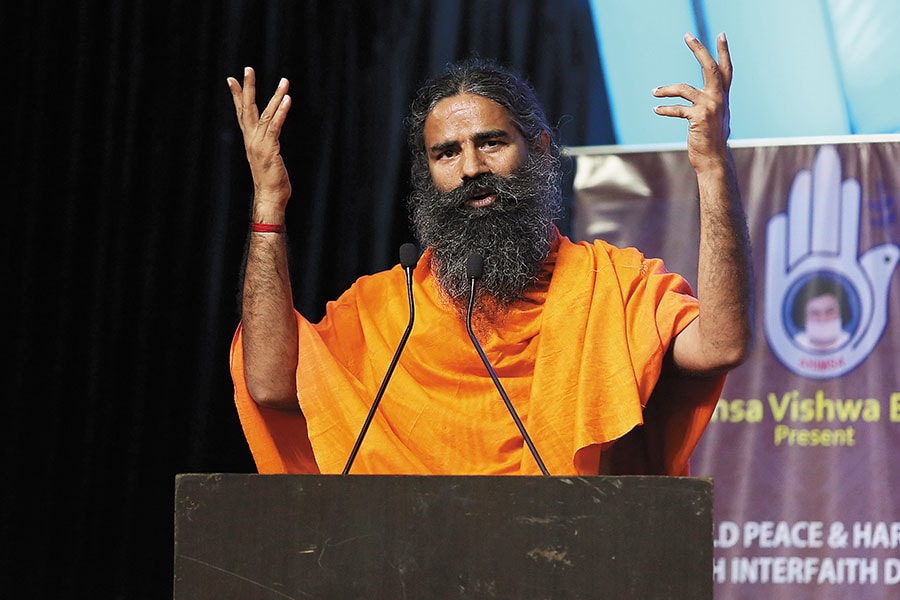

Baba Ramdev took on MNCs with Patanjali

Baba Ramdev took on MNCs with PatanjaliImage: Getty Images

Clearly, something was wrong somewhere. In Dabur’s case it was its obsession with the bottom line. “We were concentrating more on protecting profit and had adopted a somewhat defensive posture towards disruptive competition,” Duggal recounts. This, he adds, was only encouraging the competition to get more disruptive.

For a company that traces its ayurvedic lineage way back to the early 1880s, ceding ground to a Johnnie-come-lately was a bitter pill to digest. The medicine, though, was needed. And its effect is evident today.

Three years after the Patanjali jolt, Dabur is back on song.

In the first quarter of fiscal 2019, honey sales jumped by 41.60 percent over a year ago and market share climbed to 54 percent. And Chyawanprash has hit its best value market share at 61 percent. Also, when Colgate and HUL’s Pepsodent were losing market share to Patanjali’s Dant Kanti, Dabur managed to increase toothpaste share. “We have changed our attitude. We will attack rather than defend, and protect market share and volumes rather than shield profit,” asserts Duggal, adding that there would be no let-up in the aggression.

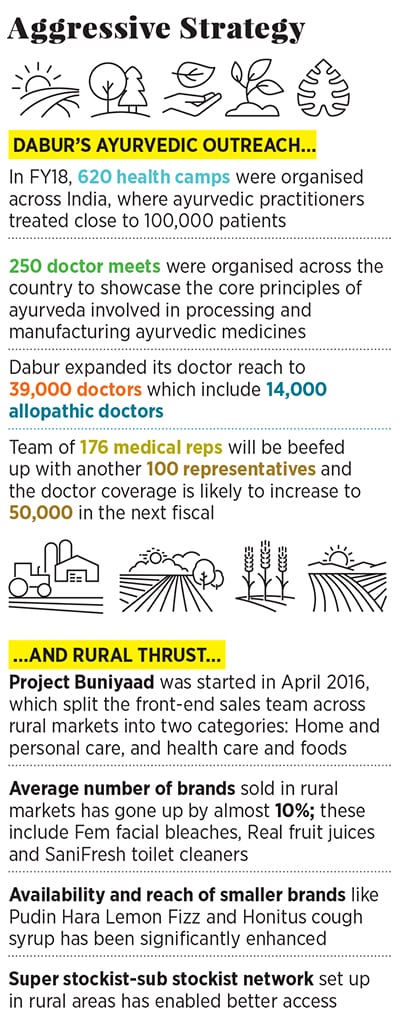

Amit Burman, vice chairman of Dabur, asserts that Dabur’s ayurveda is based on science and not faith. “We have a lineage going back 130 years, which nobody can claim,” he says. During the last fiscal, 620 health camps were organised across the country, where ayurvedic practitioners treated close to a lakh patients. Over 250 doctor meets were organised to showcase the core principles of ayurveda involved in processing and manufacturing ayurvedic medicines.

The combative avatar of Dabur comes at a time when Ramdev is believed to have assembled an over-10,000-strong sales field force to fan out in rural India. As Patanjali starts losing steam in cities—bogged down by quality perceptions and spreading itself too thin into areas such as dairy and agri—the next wave of growth is likely to come from the hinterland. Dabur, which gets 46 percent of its sales from rural India, is ready for that challenge.

“We will meet fire with fire and will be far more aggressive in defending our market share than we have been in the past,” Duggal thunders. If Dabur could do it in honey, by offering a value proposition, it feels it can do it elsewhere, too.

The honey turnaround had many components: Though price was not cut, grammage was increased by 30 percent for the same price, and quality was reinforced among consumers by communicating that the product had the backing of regulatory body Food Safety and Standards Authority of India. “We knew that this (shift of consumers to Patanjali) may not last for long as our product is inherently superior,” recounts Duggal, adding that a 9 percent price cut happened after GST rates were slashed last July.

While consumers did gravitate back, what also helped Dabur were the chinks in Ramdev’s armoury. Although Patanjali aggressively expanded the market for packaged honey, due to product quality and supply chain issues, consumers lapsed out, reckons Credit Suisse in a recent report. Dabur’s differentiated marketing also did its bit in expanding sales. The company’s campaign on using honey to replace sugar for weight loss strongly resonated with health conscious consumers.

The lessons from honey were learnt quickly. Dabur now doesn’t intend to use its scale advantage to increase prices beyond a certain level.

In another departure from its core operational philosophy, Dabur took a tactical diversion by adopting a flanking strategy. The idea, explains Duggal, was to build moats around brands, in terms of better pricing or by launching flanker brands, which can be a satellite to the main brand. Take, for instance, Dabur’s blockbuster Amla hair oil. The company didn’t cut the price but launched a range of flanker brands that were lower priced. This not only acted as a moat against intrusion into the mother brand, but also ring-fenced it against future disruptions.

“Just putting more feet on the street won’t work,” asserts Duggal. Reason: Rural demand for a product is different from urban; it requires massive distribution infrastructure, and a robust supply chain. One needs to build the whole ecosystem to drive a rural franchise, including the portfolio of brands. “It’s very hard,” he adds.

Agree FMCG analysts. Rural, they reckon, will be a different ballgame for Patanjali. “Disruptive pricing can take you to a certain level. That’s it,” reckons Abneesh Roy, senior vice president of institutional equities at Edelweiss Securities. Pushing the same kind of products without any innovations and harping on the charisma of Ramdev in advertising won’t work, he adds.

Although the jury is still out on Patanjali’s rural gambit, early signs of impending trouble are visible.

Kherli village, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh

Egged on by the swadeshi spirit of Ramdev and Patanjali, Tej Singh opened a Patanjali store three years back. Sales, to begin with, were brisk. Dant Kanti toothpaste and cosmetics were the top-sellers, followed by biscuits, oats, vitality brand Shilajit and Swet Musli Churna—described on Patanjali’s website as ‘herbal Viagra’.

Today, however, sales are stagnating. Singh, 75, doesn’t know what went wrong. What he offers are conjectures such as more herbal and ayurvedic options available to consumers, people getting hooked to online shopping or even dissatisfaction with the products. One major issue, he identifies, is supply constraints and refusal of the company to take back expired stock.  Narottam Giri, Dabur’s rural sales promoter, visits a grocery store in Shivali village, UP, to boost toothpaste sales; Dabur products on sale (right)

Narottam Giri, Dabur’s rural sales promoter, visits a grocery store in Shivali village, UP, to boost toothpaste sales; Dabur products on sale (right)

Image: Madhu Kapparath

“Look at the heap of all these products,” he says, pointing to a couple of neatly-packed cartons stuffed with expired products lying on the top shelf of the store. “Patanjali doesn’t want it back and consumers won’t buy,” he rues. Nishant Bhati, Singh’s grandson, chips in. “How long can you take the losses? Even the margins have fallen,” he laments, adding that the shop has started selling cattle feed to beef up its revenue.

Patanjali declined to comment for this story.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

“Overall, the Baba Ramdev story has been great for us. Patanjali has impacted the business more positively than negatively.”

“Overall, the Baba Ramdev story has been great for us. Patanjali has impacted the business more positively than negatively.”