Cooking up a storm

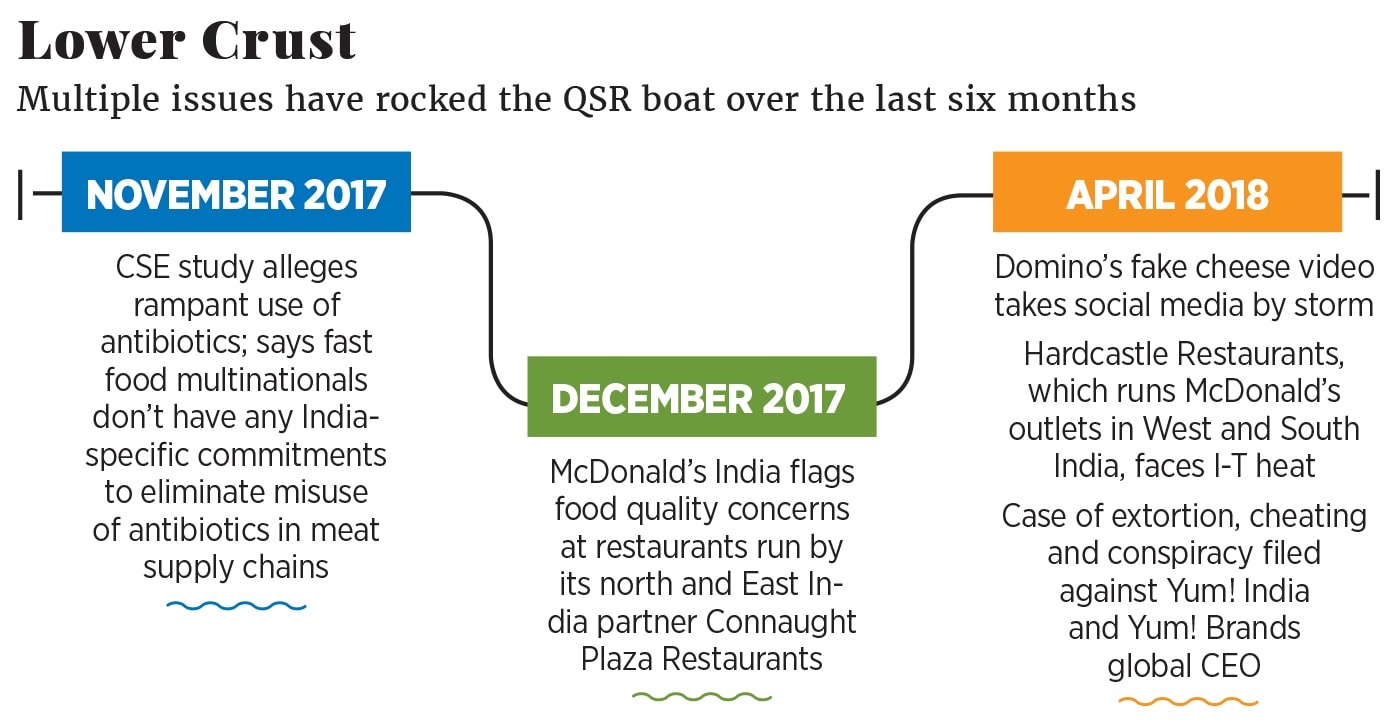

The recent 'fake cheese' video is among a spate of incidents that threatens to derail the QSR industry that was just about getting its act together

Pratik Pota, CEO, Jubilant FoodWorks

Pratik Pota, CEO, Jubilant FoodWorksPhotographs: Madhu Kapparath

“It was rubbish,” recalls Pota, alluding to the Domino’s ‘fake cheese’ video that went viral on social media last month. The video alleged that Domino’s used fake cheese in its pizzas, and some of its products allegedly contained large amounts of fat and saturated fat. It was “so factually wrong”, Pota claims, that “we thought that it would find no believers”.

“Every single thing that was being said in the video was wrong,” claims Pota. Though the allegations turned out to be false, the damage it did in terms of swaying the sentiments of consumers was immense.

Domino’s, though, was not alone in finding itself in a soup. Last month, the Income Tax (I-T) department reportedly conducted searches on nearly 20 premises of Hardcastle Restaurants Pvt Ltd (HRPL), one of the master franchisees of McDonald’s that runs its outlets in West and South India.

More trouble was in store for the QSR (quick service restaurant) industry. One of the former franchisee partners of Yum! India, which operates brands like KFC, Pizza Hut and Taco bell, filed a case of extortion, cheating, criminal intimidation and conspiracy against top officials of Yum! India, Yum! Brands Global CEO Greg Creed and private equity firm Samara Capital Partners Fund II last month. Yum! India has denied all allegations. “Yum! strongly condemns the baseless allegations made by a former franchise partner with whom we ended our relationship after it defaulted on payments to Yum!, vendors, real estate owners, employees, and towards its statutory liabilities,” a Yum! India spokesperson told Forbes India. “Continued efforts by the complainant seem to be driven with malicious intent to harm our brand,” the spokesperson adds.

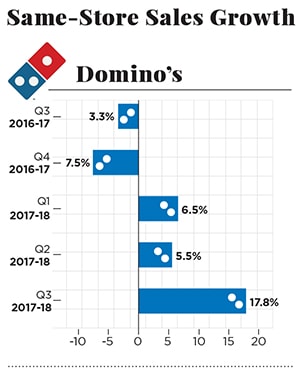

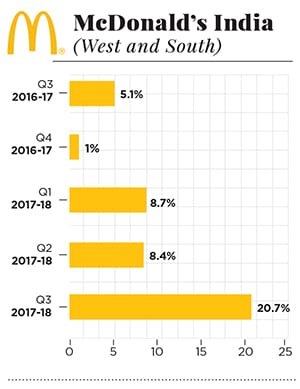

The timing, reckon food experts, appears terrible. “Just when the QSR was staging a comeback by posting decent same-store growth numbers over last few quarters, it gets hit by such news,” says Rohit Malhotra, business head of Barcelos India, a South African restaurants chain. Social media, whether we like it or not, has the power to make or break a brand. “The news could be fake but the damage can be real,” says Malhotra, who has drastically scaled down his expansion plans. Barcelos now has four stores, with another four slated to open by the end of the year.

Sitting relaxed at his plush corporate office at MG Road in Gurugram, Menon reckons that it was the inherent resilience of the brand that prevented the video clip from clouding the judgement of the viewers and consumers.

Sitting relaxed at his plush corporate office at MG Road in Gurugram, Menon reckons that it was the inherent resilience of the brand that prevented the video clip from clouding the judgement of the viewers and consumers. “A lot is defined by the power of the brand and the trust that the community and consumers have in it,” he says. Though the brand was resilient enough to weather the storm, Menon concedes that negative news of any kind does impact the category. “Whatever happens to any brand eventually impacts the category,” he says.

Take, for instance, the report by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) last November about the double standards adopted by multinational QSR brands when it came to regulating the antibiotic content in the meat. In March, CSE reiterated rampant antibiotic misuse in the Indian poultry sector.

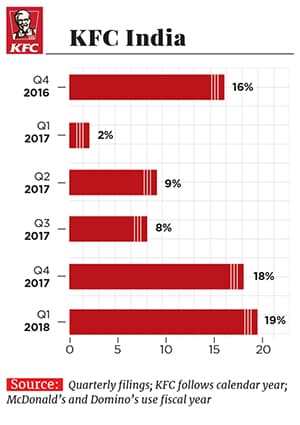

Menon, for his part, claims that KFC has always adhered to the law of the land. “We assure all our consumers that our suppliers who give us chicken are in absolute adherence to WHO principles,” he says, claiming that all the chicken that gets supplied to KFC is antibiotic-free. “We want to make sure this is something the consumers are aware of,” he says, listing out the steps that KFC has recently taken in rolling out healthy offering. Two of them: To naturally grow ingredients in terms of flavours and colours, and a switch from palm oil to rice bran oil, which is said to lower cholesterol.

What has also helped the American chicken brand stage a comeback (see chart) was a rejig of its plans in India. “First, we did some restructuring,” Menon points out. Since some of the franchisee partners were not adding to the growth, Sapphire Foods, formed by a consortium of funds led by Samara Capital, was roped in to consolidate small partners. “This helped us unlock the growth opportunities,” adds Menon, before moving on to the second element in the game plan to reclaim lost ground: Focusing on its core offering of chicken. Such initiatives helped drive growth—ranging from 2 percent to 18 percent—across six quarters over 2016 and 2017.

Though Menon reckons that the fundamentals of the QSR industry in India are strong enough to tide over any crisis, the chances of negative news snowballing into ‘terrible news’ are quite high. Reason: A brittle ecosystem. Over 650 QSR and café outlets shut down between 2013 and 2016 in India, according to a study done by TagTaste, a professional network for food industry, last year. What’s even more alarming is the prediction for this year: While 40 percent of QSR outlets will have 0 percent or negative store profitability, 35 percent will barely manage to stay profitable at store level.

For a bunch of new burger players that entered India in 2015 with a bang, the going has been tough. Wendy’s, the world’s third largest burger chain, had ambitious plans to open 40-50 outlets in five years. In three years, it has opened just two. Another American burger chain, Carl’s Jr, also reportedly set an audacious target of opening 100 outlets in five years. Two and a half years since it set foot in India, the store count languishes in low single digits.

Samir Menon, Managing Director, KFC India

Sabharwal peels off another layer of QSR to explain what is going wrong with the industry: Entry-level products are losing their value proposition, leading to a massive drop in traffic. Take, for instance, the Aloo Tikki Burger at McDonald’s. Its price increased by `9 in 13 years, from `20 in 2004 to `29 last year. “This is less than a 3 percent increase every year,” he says. After the rollout of GST, the aloo tikki has been priced at `35, a jump of 7-8 percent. For every 5 percent price increase, demand shrinks by 7.2 percent, he calculates.

To add to the woes, online food aggregators, such as Zomato and Swiggy, have been nibbling into the market share. However, Sid Talwar, partner at Lightbox, a venture capital fund, contends that the performance of QSR players reflects the weak fundamentals of the sector. “If brands aren’t growing, it isn’t due to online food aggregators, or competition from newer independent brands, or flagging sentiment because of a few incidents,” says Talwar, whose venture capital firm has backed online food tech startup Faasos. More often than not, he explains, these problems are self-inflicted. Talwar explains how: A sub-standard food experience, lack of innovation in food quality and range, spending more money in marketing and rent. “Till now, many of them have gotten away with it due to the lack of choice in the market. But now, times are different,” he says.

Singh adds that just when the QSR companies were warming up to the idea of healthier offerings, the fake cheese video hit the segment. “The news was sensationalised, and people remember bad news more than good news. And it impacts consumption.”

Pota of Jubilant FoodWorks is conscious of the collateral damage. “In the age of technology and social media, every consumer will end up being a media publisher.” The challenge, he explains, is to ensure complete transparency, and extensive communication. Domino’s, claims Pota, uses 100 percent real mozzarella prepared from real milk. The signature Cheese Burst Pizza is also made from the 100 percent mozzarella and has a liquid filling that contains real cheddar and other dairy products. A brand needs to ensure that what a consumer sees is what she gets. “You cannot be a brand that stands for something on television and something different inside the store,” he says.

Such incidents will recur, and Pota reckons the industry needs to learn to live with them. There will be people who will have good experiences across thousands of stores, but there would be many with bad experiences as well. “The bad ones will get more word of mouth. As an industry, we need to learn to navigate this.”

Domino’s is not alone in striking a conversation with consumers. McDonald’s too has been doing its bit to spread the news about the steps it has taken for a healthier menu. Hardcastle Restaurants, which runs its outlets in South and West India, has reduced oil content in mayonnaise by up to 40 percent, cut sodium in patties, fries and nuggets by up to 20 percent and has kept food trans fat-free. It makes soft serve by using 100 percent milk, wraps multi-grain, and patties artificial preservative free, claims its spokesperson in an email. “Our food is wholesome, hygienic and nutritious, is compliant with applicable food law and can safely form part of the regular diet of our customers,” the spokesperson added.

Though fake cheese and other episodes won’t usher in an apocalypse, it does give the QSR industry something to chew on. “The days of QSR brands are definitely not over but they must adapt to a new-age framework that involves transparency with consumers, regulators, business partners and environment,” cautions Sabharwal of TagTaste. That, after all, is how the crust crumbles.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X