How Tata Housing Reinvented Itself

Real estate slowdown? Brotin Banerjee hasn’t heard about it, having grown Tata Housing 100 percent every year since 2006. He has transformed a defunct company into a serious player

He was considered a rising star in the Tata firmament. Eight years into the elite Tata Administrative Service (TAS) and he had notched up several credits that proved he had what it takes to go the distance.

Brotin Banerjee had a stint with Tata Chemicals. He launched a lower cost variant of Tata Salt and also a new distribution model. Success noted. Next, he got a big up with a promotion to chief operating officer of Barista—at the ripe young age of 29. Banerjee fixed a sagging bottom line at the coffee chain. He’d seen the vibrancy of a young brand and led a passionate team.

It was then that he—and the system—got a shock. In 2006, when everybody would have expected a plum assignment in a major Tata company, he got a dud—an almost defunct company. Among the close to 100 businesses that existed under the pater familias Tata Sons, there was a housing company that few knew much about—or cared about. In fact, things were so bad that Tata Housing Development Company was then known more by its acronym THDC since it could not afford to pay the royalty to carry the Tata name.

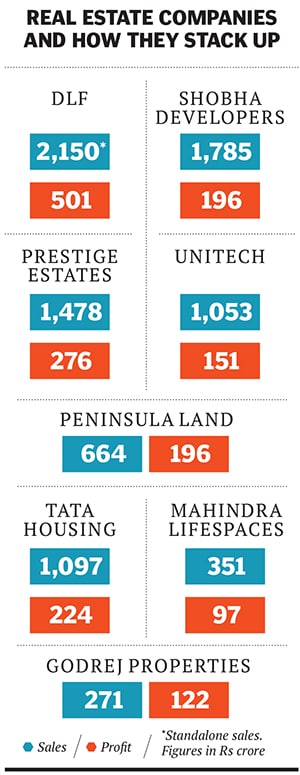

THDC was an oddball player in 2006 because the rest of the industry was booming. Developers were fiercely bidding up land prices to build large land banks. DLF, the country’s largest real estate company, got a dream valuation of Rs 20,000 crore when it launched its initial public offering (IPO). The Tatas were then just waking up to the realisation that they were missing something here.

And so Banerjee found himself in a small flat in Emerald Court in Mahim, Mumbai (THDC’s office) as deputy CEO of a company that had a negative net worth of Rs 10 crore, which means its liabilities exceeded its assets by Rs 10 crore.

Cut to the present, and Tata Housing has seen nothing but a dizzying climb. Over the last half decade, it has grown at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 100 percent and clocked revenues of Rs 1,097 crore in the year ended March 2013. Simply put, the business has doubled every year and the company is currently constructing 70 million square feet of saleable properties across the country. “They’ve managed to get here due to their focus. Unlike other developers they never sacrificed long-term stability for short-term gain,” says Shobhit Aggarwal, managing director, capital markets, at Jones Lang LaSalle, a real estate services firm.

The Initial Days

How did Banerjee do it? Without a land bank, and without any borrowing capacity worth speaking about? People in the industry grudgingly admit today that not many of them had given Tata Housing much of a chance.

Banerjee was also hamstrung by the fact that no one wanted to join the company. “I would have people come in through the door and their first question was—why can’t you use the Tata name?” he says. He knew he needed to do things differently. So he hired people from different sectors (not real estate) who came with new business ideas and attitudes.

The next crucial phase was to get business flowing. Here too it was Banerjee’s contrarian approach that worked. Tata Sons pitched in with Rs 100 crore of equity. But in the go-go years before 2008, that was hardly enough to purchase land. And the company didn’t have a balance sheet to support large borrowings from banks.

That was when Banerjee realised that, to get started, he needed to look outside the traditional housing business model. He and his management team noticed that while there was a bubble building up in the premium and luxury housing categories, the affordable and low-cost housing space was experiencing a huge shortage. The company estimated a shortage of 24.7 million units with most of the shortage falling in the affordable housing space.

Among the first projects the company launched was a low-cost housing development in Boisar, an exurb (commuter town) of Mumbai. Here they constructed over 2,000 units at costs ranging from Rs 5 lakh to Rs 15 lakh. Now, affordable housing is not something developers were looking at in 2007. But when the real estate market cracked in 2008, it proved to be a wise bet.

While working on the project, Banerjee realised that he needed to re-engineer the entire process of how real estate development was thought of. Traditional developers usually sell their inventory in tranches. As real estate prices keep rising, it helps them realise gains. Moreover, developers, and at times buyers, are not too perturbed about project delays as the value of the property keeps rising.

But with low-cost housing, the dynamics completely change. Low-income buyers with stretched budgets need deliveries quickly. Selling inventory in lots doesn’t make sense as demand is usually more than supply, and the cash realised from sales helps in getting working capital. “We monetise how a manufacturing company would,” says Govinder Singh, CFO at Tata Housing.

Unlike the skills needed in the real estate industry, here manufacturing-like skills were needed.

And it was here that Banerjee decided to adopt an approach that is different from the usual cookie-cutter one. It paid off richly. His mantra: Construct quickly, hand over apartments and move on to the next project. It’s hardly a surprise that five years on, low-cost and affordable housing makes up almost Rs 500 crore of Tata Housing’s top line. The company has spun it into a new business unit called Smart Value Homes and it aims to become a leading player in the space.

The Land Issue

With low-cost housing the company got an important entry point into the business. But Banerjee saw that unless Tata Housing was able to get into other, more lucrative parts of the trade, it would never be seen as a serious player. Here financing of land was a critical issue as these projects cannot be located outside cities.

What Tata Housing needed was a capital-light model that allowed it to develop projects on prime land but without outright purchase. Aiding it was a 2008 Reserve Bank of India directive that forbade banks from lending for land purchases. That was when Banerjee decided to get into joint development agreements (JDAs) with landowners. It is a model that has found favour in the real estate industry since, but most companies, if they have the capital, still favour purchases over JDAs as they believe the upside is greater.

But the downside is also greater, when there is a slowdown. This saddles land buyers with too much debt. This story has played out at DLF, the country’s largest real estate company by revenues, which has been struggling to sell assets to reduce debt.

Tata Housing has two types of JDAs. One is where the company has a floor and a cap model. In this, the company pays the landowner a fixed cost for the land. The upside is capped at a reasonable level, say 20 percent. The advantage for the developer is that it is able to benefit if prices gallop. Several large landowners across the country now prefer going for deals like this as they still maintain some ownership of the land and get a minimum rate of return.

Another popular approach that Tata Housing takes is to use land parcels by signing a joint venture agreement and becoming a majority partner. From then on it takes care of everything—from conceptualising the project, to design, marketing, construction and delivery. The landowner gets a fixed percentage of the topline.

Branching Out

Over the last three years, Banerjee has moved quickly to de-risk parts of the business. One way of doing this has been to get into different types of housing projects. So, apart from low-cost and affordable housing, the company is also in premium and luxury housing. It recently launched a second homes project in Kasauli, Himachal Pradesh, which has been doing well. And most recently, it ventured into old-age homes in Bangalore.

“What this does is ensure that the company does not suffer too much if a certain segment is impacted by a slowdown,” said an analyst at a foreign brokerage, who declined to be named.

Along the way, the company has had some particularly successful launches. In April, in the Delhi suburb of Gurgaon, it decided to launch a block of flats in Sector 112 at Rs 2,000 more (than the prevailing price) per square feet. While they knew they’d got the location and pricing right, the response surprised even them. On the first day, the number of buyers was 11 times that of the flats available, as people flocked to the Tata brand and the assurance it brought. The company had to hold a lottery to determine whom to assign the flats to. However, it has not had this success with all its projects. There are some projects, like the La Montana project in Pune, which are struggling.

But having tasted success, Tata Housing is not looking back. At a time when there are signs of an extended real estate slowdown, the company plans to step on the gas. Last December, Tata Sons infused Rs 500 crore into Tata Housing. It’s a sign of the faith the management has in the business.

Banerjee admits that from here on it will be difficult for the company to double revenues every year but he aims to take the business to Rs 5,000 crore in the next three to four. Recently, in a first for a real estate company, Tata Housing got a construction loan at base rate. It has also been able to raise short-term commercial paper at 9 percent which is significantly cheaper than what other companies manage to get.

Banerjee clearly has put his stamp on the company. The 39-year-old TAS official is coy when asked whether he is done with Tata Housing, but is obviously up for the challenge if it comes his way.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)