Crisil: Beyond ratings

India's largest credit rating agency has continuously upped its innovation game and transformed itself into a global analytical powerhouse

Ashu Suyash, managing director and CEO of Crisil, took charge in June 2015

Image: Mexy Xavier

It was 1994 when Ashu Suyash—then an executive in the financial institutions group at Citibank in India—along with senior executives was quizzed by a Crisil team of analysts as part of a ratings exercise. The foreign bank was seeking to raise tier II debt and this was the first time in India that a subsidiary of a foreign entity was being rated by an Indian company.

“They asked all the tough questions, from profitability of the subsidiary to P&L data, debt-raising steps and strategy for growth,” says Suyash, who was oblivious to the fact that a few decades later she would lead the company. Apart from the analysts, the Crisil team had heavyweights such as the then managing director and CEO, late R Ravimohan, and senior analyst and future leader Roopa Kudva at the meeting.

Later, when she was heading Fidelity’s asset management business in 2012, Suyash had witnessed a similar round of questioning from Crisil to assess the quality of the fund house, mutual fund rankings and financing needs. In March 2015, Suyash was approached to lead Crisil after Kudva quit the firm after 23 years there, including eight as CEO.

“All these thoughts [of my previous interactions with Crisil] came to mind. I knew the company and people well,” says Suyash, now managing director and CEO of Crisil. “I often tell my team about this, it is like Intel Inside [referring to the popular marketing phrase of the IT giant].”

Her entry into Crisil, however, came with its own set of challenges: She had never been a ratings analyst and was an ‘outsider’; her predecessor Kudva had risen up the ranks to become CEO.

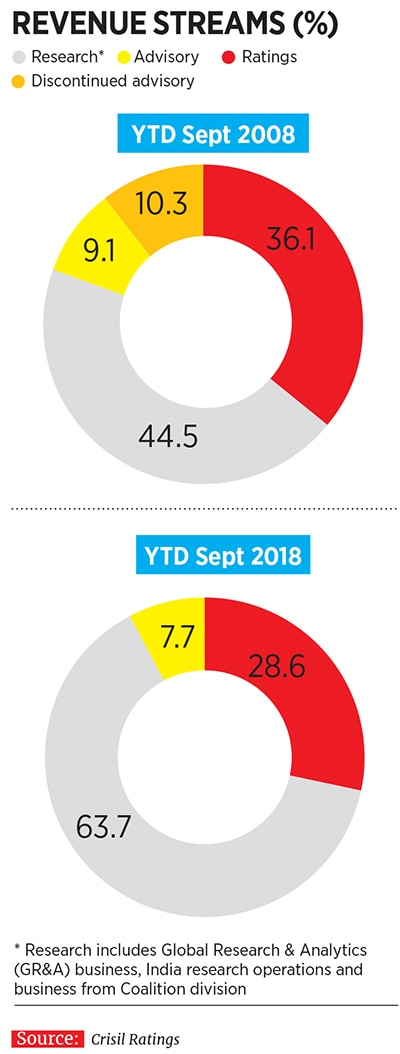

Crisil, India’s largest ratings firm, over the 30 years since its inception has had a history of diversifying and changing its business model. And what was once its only source of earnings—fee income through credit ratings of debt instruments is today not its main source of income. It is now Global Research and Analytics (GR&A). Business-wise, nearly 64 percent of Crisil’s revenues comes from research, 7.7 percent from advisory and 28 percent from ratings, as of September 2018 (see chart).

The research business grew by 371 percent in the past nine years ending September 2018. The advisory business, too, is growing at a faster pace than the ratings business—at 143 percent for the same period, compared to 108 percent for the ratings business. Seventy percent of Crisil’s revenues come from outside India, powered first by an increasing engagement with its majority shareholder S&P and the 2012 acquisition of a UK-based analytics firm Coalition Development, which provides high-end analytics to some of the world’s largest global investment banks. As global banks have turned their focus to risk management and stress testing, Crisil has also been building models for them, through quantitative analysis.

Now, from the traditional fundamental analysts which Crisil—and all credit rating agencies—used to employ in the 1990s, data scientists and analysts specialising in applied mathematics and physics are being sought for analytics.

Crisil is India’s largest credit rating agency by revenue market share of around 30 percent, followed by CARE with 28 percent and ICRA with 21 percent, according to Centrum Broking. The balance includes companies such as Fitch’s India Ratings and Research, and Brickwork. Crisil leads in rating debt instruments and SMEs, while CARE is the leader in bank loan ratings business.

Crisil reported a 10 percent jump in consolidated total income for the three months to September 2018 to ₹454.22 crore, compared with ₹413.68 crore in the corresponding quarter last year. Net profit rose by 29.66 percent to ₹90.01 crore against ₹69.42 crore in the corresponding quarter of the previous year.

For a company whose earnings are largely fee- and advisory-based, Crisil has rewarded its investors well: If a person had invested ₹1 lakh in Crisil in 1993, when the ratings company was listed, it would be worth ₹1.59 crore, which works out to an average compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 22.8 percent over 25 years.

FROM RATINGS TO ANALYTICS

Conceptualised and founded by veteran former bankers Pradip Shah and Narayanan Vaghul, Crisil was the pioneer in credit ratings in India in 1988. Even in its early days, credibility and innovation became the underlying buzzwords for the company. Crisil insiders point out that Shah was more entrepreneur than professional, keen to build the brand and image of the organisation. Shah, then 34, brought in marquee shareholders into Crisil. These included State Bank of India, ICICI Bank, HDFC, General Insurance Corporation of India, LIC and a string of foreign banks which included Bank of Tokyo, HSBC and Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Until the mid-1990s, ratings was the core business of Crisil, with 90 percent of revenues coming from India.

The business of credit rating succeeded in India at a time when countries such as Israel and Malaysia were not so successful. “We decided from inception to remain neutral and not work only for investors or against issuers,” Shah, chairman of IndAsia Fund Advisors, tells Forbes India. Companies which sought to be rated paid fees and the rating they received influenced clients. But Crisil understood the risks it faced from having a monoline type of business, where income was dependent on the number of issuances of paper.

In 1997, global ratings giant Standard & Poor’s (S&P) bought the 9.68 percent that ADB had held in Crisil since inception. This was under the leadership of Ravimohan, who was keen to look for new business lines and partners to deal with. S&P has, in phases, hiked its stake in Crisil to 67.64 percent, as of September 2018.

Crisil then pioneered SME ratings in India in 2005, a brainchild of Kudva and supported by Ravimohan, when it was a completely untapped segment for business. “In the mid-2000s, we expanded our scope to work with S&P to help them with their big corporate portfolio, writing rationale, industry overview, thematic and company reports,” says V Srinivasan, president (GR&A), Crisil. This included companies such as GE and sectors such as health care and telecom.

Crisil’s next big move was to acquire Irevna Research, whose equity research business complemented Crisil’s credit rating business. With centres in Argentina, Poland, US and China, besides India, this acquisition—for ₹31 crore in 2005—has a business that has grown 20-fold, says Suyash. An Axis Capital report said that Irevna posted a profit of ₹39.4 crore in FY17.

GR&A now contributes 45 percent and Coalition the balance 20 percent to Crisil’s overall research business.

Coalition is a giant in the field of analytics, providing benchmarking, competitive intelligence and client analytic reports to 33 global investment banks. Its key differential from rivals is providing its clients with insights into where they stand in the market and how their competition appears to be faring, says Stephane Besson, CEO of Coalition.

While the commercial banking world is seeing flattish growth, Besson says their business is recession-proof. “When the economy is up, banks are keen to know who is performing better; when it is down, they seek to understand which clients can be tapped and how to better allocate resources and capital,” he says. Coalition reported a profit of ₹59.7 crore in FY17, according to analysts. Crisil declined to disclose the independent profits for Irevna and Coalition.

Like its parent, Coalition continues to scout for newer businesses. “We have started to look for business beyond commercial banks. This will start by tapping wealth management businesses from its current investment banking clients, in 2019, followed by asset management businesses in 2020 and retail banking in 2022,” says Besson, who estimates the company’s revenues have grown by 15-20 percent this year.

Business for several credit rating agencies, including Crisil, also started to change post the 2008 economic slowdown. Since then global banks have been more focussed towards risk management, credit risk advisory and consultancy. “Model risk is a big part of my business,” says GR&A’s Srinivasan.

Crisil, in its next phase of growth, started to structure quantitative models for banks, in the areas of foreign exchange, credit, equity and fixed income. It is involved in creating forward forecasting and yield curve models which would see how interest rates would move in the future.

Suyash says Crisil, through Coalition and its GR&A business, is working with the world’s top 10 global banks helping them meet their risk and regulatory obligations. This involves helping banks with stress-testing solutions and monitoring key risk indicators.

It also offers infrastructure advisory services to various agencies, institutions and ministries of the Indian government and several global multi-lateral agencies such as the World Bank, ADB, IFC among others. In its advisory business, Crisil completed one more acquisition in 2018, of Pragmatix, which provides data intelligence services.

“Crisil and ICRA have a more diversified revenue profile, but CARE gets most of its revenues from its ratings business, hence it is more prone to macroeconomic cyclicality,” says Aditya Baghul of Axis Capital. “Crisil has developed a stable business model with a well-diversified revenue base, where research [and analytics] has gained prominence with its share increasing.”

THE IL&FS DEBATE AND ALTERNATIVE DATA

Crisil’s peers ICRA, and India Ratings and Research, which rate infrastructure lender IL&FS’s commercial paper, have come under the spotlight for failing to spot the financial trouble it had got into. Crisil does not rate IL&FS. Suyash declined to comment on the matter. But an industry source says, “Nobody is asking what the lenders were doing when IL&FS got rated. Nobody knows where to hang the coat and the rating agencies are where the coat appears to hang nicely.” Rating agencies, says the source, must continue to learn, hence availability of financial data is even more critical in the future and for rating unlisted companies.

Former Sebi and IDBI chairman M Damodaran, who is also a director on Crisil’s board, says: “Rating analysts should not get taken in by what the rest of the world believes or what they get taken in by. They should always retain a professional scepticism and constantly question what could possibly go wrong from here.”

Damodaran also believes there are too many credit rating agencies in India. “We don’t need more (that does not mean they need to merge or close down). But there is no room for more business to do,” he says. He also feels the ratings policies need more intervention from the two regulators, the Reserve Bank of India and Sebi. The biggest challenge for Crisil, however, is to continue to retain talent and to look for newer forms of business.

Crisil’s senior analysts are now being trained in Python and R, both high-level open source programming languages, which will help boost their quantitative skills. Srinivasan says Crisil is already exploring usage of alternative data. “We are trying to use alternative data—how to use satellite images to forecast developments in some sectors. Also if we can use data from one industry to determine trends for another,” he says. He adds that alternative data firms globally are also exploring if CCTV data at malls, used to determine footfalls in retail business, can be used to predict which businesses are not likely to do well in a particular season. It is certainly something quantitative analysts at Crisil, too, will attempt to crunch out in the future.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X