Jaquar: Seeing business in a new light

The Mehra brothers built Jaquar into one of India's foremost sanitary ware brands by refusing to crouch when things went awry. Now, the next-gen is seeing the family business in a new light

(Left to right) Parichay Mehra, Rajesh Mehra, Krishan Mehra, Ajay Mehra, Kanav Mehra and Rabhir Mehra

(Left to right) Parichay Mehra, Rajesh Mehra, Krishan Mehra, Ajay Mehra, Kanav Mehra and Rabhir Mehra Image: Amit Verma

Rajesh Mehra knows a thing or two about cricket, especially about playing a bouncer on a grassy wicket. “There are only two ways to do it,” reckons the director and promoter of the bath fittings and sanitary ware maker Jaquar group. “Either you duck or you hook,” he says. “I have always hooked because ducking won’t take you anywhere. It makes you a sitting duck.”

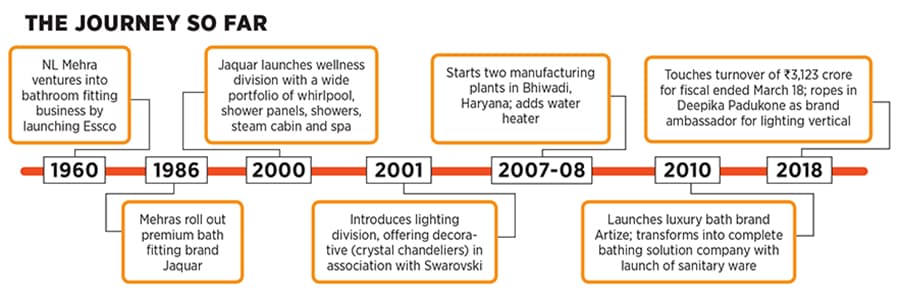

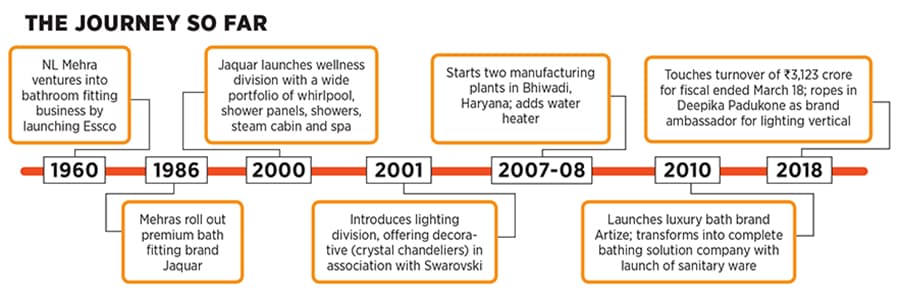

In 1986, when Rajesh, 59, along with brothers Ajay and Krishan, padded up to start his innings with the then newly-launched Jaquar brand, he was up against a barrage of bouncers. Dealers were reluctant to place a bet on the rookie brothers, architects acted pricey and the market was largely unorganised with no established brand. Consumers, it seemed, were unwilling to pay a premium for a branded product as bath fittings were seen as a commodity. The fact that the Mehras were in this business since the ’60s, when Rajesh’s late father NL Mehra started the bath fittings company and brand Essco, wasn’t of help either.

In 1986, when Rajesh, 59, along with brothers Ajay and Krishan, padded up to start his innings with the then newly-launched Jaquar brand, he was up against a barrage of bouncers. Dealers were reluctant to place a bet on the rookie brothers, architects acted pricey and the market was largely unorganised with no established brand. Consumers, it seemed, were unwilling to pay a premium for a branded product as bath fittings were seen as a commodity. The fact that the Mehras were in this business since the ’60s, when Rajesh’s late father NL Mehra started the bath fittings company and brand Essco, wasn’t of help either.

Business was minuscule, the forecast looked gloomy and the gambit of starting a new brand seemed like a blunder. “We didn’t duck, which would have meant waiting for things to happen,” says Rajesh. “We took a leap of faith,” he says, recalling how the brothers ditched the dealer route and connected directly with potential consumers.

Business was minuscule, the forecast looked gloomy and the gambit of starting a new brand seemed like a blunder. “We didn’t duck, which would have meant waiting for things to happen,” says Rajesh. “We took a leap of faith,” he says, recalling how the brothers ditched the dealer route and connected directly with potential consumers.The move paid off. In three decades, the Mehras have turned their family-owned group into an over-₹3,000 crore (by revenue) business, which makes it one of the biggest players in the Indian sanitary ware segment.

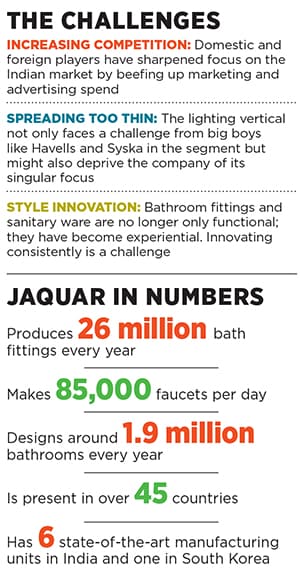

Jaquar—named after Jai Kaur, the grandmother of the Mehra brothers—closed the fiscal ended March 31, 2018, with revenues of ₹3,123 crore, and claims to be a profitable, debt-free company. Over 80 percent of the revenue—₹2,537 crore—comes from the group’s flagship Jaquar brand, which caters to the premium segment, while the rest comes from sub-brands Artize and Essco besides the group’s budding lighting division.

“My father started Essco from scratch, and we started Jaquar from zero,” says eldest brother Krishan, 61. “We had faith in ourselves and the product. We knew we could make our own brand and destiny,” he adds.

First Mover

It was in 1960 that NL Mehra took the entrepreneurial plunge, along with a friend, to start Essco from Delhi. Among the few to create a brand in this highly unorganised segment, Mehra faced an uphill task in changing mindsets. Reason: Bathroom fittings were sold as a commodity, and no one saw the value of a branded product. What was driving the market was a push by dealers and real estate players, who largely relied on imports. The partners slogged it out for a decade in a hostile pitch.

In 1972, the duo started its first manufacturing plant in Haryana, and after three years rolled out a design range of bathroom fittings under the sub-brand Deluxe. “It clicked and did wonders,” says Rajesh. Two business strategies were devised, he lets on, to grow the business: Establishing an extensive network of dealers and standing out in a cluttered market with high-quality, exquisitely-designed products. By the mid-1980s, Essco had not only become a pan-India player with three manufacturing units, but was also the largest selling in North India.

In 1972, the duo started its first manufacturing plant in Haryana, and after three years rolled out a design range of bathroom fittings under the sub-brand Deluxe. “It clicked and did wonders,” says Rajesh. Two business strategies were devised, he lets on, to grow the business: Establishing an extensive network of dealers and standing out in a cluttered market with high-quality, exquisitely-designed products. By the mid-1980s, Essco had not only become a pan-India player with three manufacturing units, but was also the largest selling in North India.

The success, though, sowed the seeds of discord between the partners. “My father wanted to scale the business and expand it but his partner was conservative,” recounts Rajesh. The result was catastrophic. In 1986, the business was divided and the rights to Essco were shared. It was soon after this split that the second-generation brothers stepped in.

The beginning was dramatic. The trio decided to put Essco on the back-burner and build a new brand. The move, though audacious, appeared foolhardy. “Existing dealers panicked and backed out. Architects shunned us and we didn’t have any connect with consumers,” recalls Ajay, 56, the youngest brother. “It was the first big crisis,” he says. The brothers, however, stayed positive and determined. What gave them self-belief was the emotional connect they had with their grandmother Jai Kaur.

It was in 1960 that NL Mehra took the entrepreneurial plunge, along with a friend, to start Essco from Delhi. Among the few to create a brand in this highly unorganised segment, Mehra faced an uphill task in changing mindsets. Reason: Bathroom fittings were sold as a commodity, and no one saw the value of a branded product. What was driving the market was a push by dealers and real estate players, who largely relied on imports. The partners slogged it out for a decade in a hostile pitch.

The success, though, sowed the seeds of discord between the partners. “My father wanted to scale the business and expand it but his partner was conservative,” recounts Rajesh. The result was catastrophic. In 1986, the business was divided and the rights to Essco were shared. It was soon after this split that the second-generation brothers stepped in.

The beginning was dramatic. The trio decided to put Essco on the back-burner and build a new brand. The move, though audacious, appeared foolhardy. “Existing dealers panicked and backed out. Architects shunned us and we didn’t have any connect with consumers,” recalls Ajay, 56, the youngest brother. “It was the first big crisis,” he says. The brothers, however, stayed positive and determined. What gave them self-belief was the emotional connect they had with their grandmother Jai Kaur.

Despite all odds, the gritty brothers decided to stick to Plan A: Pushing Jaquar. The game plan was simple—come up with advanced quality products, focus on design and talk directly to consumers. “We brought our first customer from Delhi to Manesar, showed him the products and persuaded him to buy them,” recalls Ajay, adding that the turnover after the first year was a paltry ₹30 lakh.

The crisis, though, had a silver lining. “It taught us that the right way to build a brand is not through dealers,” says Rajesh. Jaquar started tapping into builders, engineers and retail consumers through small exhibitions, directly reaching out to them. A customer care service, something unheard of in the bathroom fitting industry, was started. Right from installation to repair, the brand made itself available to consumers. The move achieved two things. First, it instilled confidence among consumers and enhanced the credibility of brand Jaquar. Second, it conveyed a message to the builders and dealers that the brand was in it for the long run.

The focus, at the same time, shifted to enhancing quality. In 1987, Jaquar became the first brand to launch products that met international specifications. Over the next few years, it started gaining acceptability and the business seemed to be on track.

Another crisis, however, was lurking round the corner. A slew of multinationals (MNCs)—like the German players Hansgrohe and Grohe—entered India after liberalisation in 1991. With big-foot competition lumbering onto its turf, rivalry suddenly intensified for the Jaquar group as consumers started gravitating towards foreign labels. “This was another bouncer,” says Rajesh, who found a new way to hook it.

Sub-brands were pushed to expand the catchment area, and the focus shifted back to innovations. A research and development centre was established, products were being developed on the basis of feedback from consumers and some big marketing and advertising pushes were planned. “We were the first ones to come up with a quarter page advertisement on the front page of The Times of India,” grins Rajesh.

Make for India

The brothers devised another strategy to take on the MNCs. “We knew their strengths and weaknesses,” says Krishan, pointing out his rivals’ biggest vulnerability—imported products were designed for overseas consumers, not Indian users. “They brought [to India] the same products that they were selling in Europe,” he says. Though they ventured into Indian waters, that act, it seemed, was going to be their quagmire.

Conscious of uniquely Indian problems, Jaquar had already developed flush valves in 1988-89. The problem was complex. The body and the crystal in a flush were made of metal. Due to scaling (insoluble deposits formed by hard water), the crystal often got stuck, resulting in a continuous flow of water. The solution devised by the Mehras was simple: Do away with the metal. The re-engineered flush valve disrupted the market. “It worked and our product innovations gave us an edge over rivals,” Krishan claims.

The Mehras continued to innovate by designing products based on local conditions. For instance, in the eastern parts of India where high iron content in water results in the formation of a red layer in the flush tank, Jaquar rejigged the design of its products to ensure that the water didn’t come in contact with the metal part. “A lot of thought went into design and functional changes,” says Rajesh.

Combining aesthetics with functionality also helped. By 2009, Jaquar had crossed the ₹500-crore mark in turnover. The numbers doubled over the next two years before finally crossing the ₹3,000-crore mark in 2018.

The Mehras also inducted the third generation into the business, which resulted in the group’s foray into lighting by manufacturing chandeliers in 2001. However, Jaquar got into complete lighting solutions only in 2015-16.

The crisis, though, had a silver lining. “It taught us that the right way to build a brand is not through dealers,” says Rajesh. Jaquar started tapping into builders, engineers and retail consumers through small exhibitions, directly reaching out to them. A customer care service, something unheard of in the bathroom fitting industry, was started. Right from installation to repair, the brand made itself available to consumers. The move achieved two things. First, it instilled confidence among consumers and enhanced the credibility of brand Jaquar. Second, it conveyed a message to the builders and dealers that the brand was in it for the long run.

The focus, at the same time, shifted to enhancing quality. In 1987, Jaquar became the first brand to launch products that met international specifications. Over the next few years, it started gaining acceptability and the business seemed to be on track.

Another crisis, however, was lurking round the corner. A slew of multinationals (MNCs)—like the German players Hansgrohe and Grohe—entered India after liberalisation in 1991. With big-foot competition lumbering onto its turf, rivalry suddenly intensified for the Jaquar group as consumers started gravitating towards foreign labels. “This was another bouncer,” says Rajesh, who found a new way to hook it.

Sub-brands were pushed to expand the catchment area, and the focus shifted back to innovations. A research and development centre was established, products were being developed on the basis of feedback from consumers and some big marketing and advertising pushes were planned. “We were the first ones to come up with a quarter page advertisement on the front page of The Times of India,” grins Rajesh.

Make for India

The brothers devised another strategy to take on the MNCs. “We knew their strengths and weaknesses,” says Krishan, pointing out his rivals’ biggest vulnerability—imported products were designed for overseas consumers, not Indian users. “They brought [to India] the same products that they were selling in Europe,” he says. Though they ventured into Indian waters, that act, it seemed, was going to be their quagmire.

Conscious of uniquely Indian problems, Jaquar had already developed flush valves in 1988-89. The problem was complex. The body and the crystal in a flush were made of metal. Due to scaling (insoluble deposits formed by hard water), the crystal often got stuck, resulting in a continuous flow of water. The solution devised by the Mehras was simple: Do away with the metal. The re-engineered flush valve disrupted the market. “It worked and our product innovations gave us an edge over rivals,” Krishan claims.

The Mehras continued to innovate by designing products based on local conditions. For instance, in the eastern parts of India where high iron content in water results in the formation of a red layer in the flush tank, Jaquar rejigged the design of its products to ensure that the water didn’t come in contact with the metal part. “A lot of thought went into design and functional changes,” says Rajesh.

Combining aesthetics with functionality also helped. By 2009, Jaquar had crossed the ₹500-crore mark in turnover. The numbers doubled over the next two years before finally crossing the ₹3,000-crore mark in 2018.

The Mehras also inducted the third generation into the business, which resulted in the group’s foray into lighting by manufacturing chandeliers in 2001. However, Jaquar got into complete lighting solutions only in 2015-16.

Ranbir, Ajay’s son, heads the lighting vertical, which is still in a nascent stage. Though the division posted a modest revenue of ₹200 crore in FY18, Ranbir has set an ambitious target: Five-fold jump to ₹1,000 crore in five years. “Everybody knows Jaquar as a bathroom fitting brand. My task is to make lighting big,” he says, adding that the company recently roped in actor Deepika Padukone as the brand ambassador for its lighting vertical. The biggest learning from the second generation, Ranbir reckons, is to not squander an opportunity and stay focussed.

“We always agree to disagree,” says Parichay, son of Krishan, alluding to the chemistry between generations. “But discussions always result in improvement. The second generation encourages us to be bold and ambitious.”

The Mehras, reckon analysts, have done a commendable job in scaling up the business. “Building a ₹3,000-crore family business with zero debt is not an easy task,” avers Saurabh Jindal, analyst at Bonanza Portfolio.

Though Jaquar is a foreign-sounding name and is largely perceived as an overseas brand, it’s rare to have a homegrown company survive the might of the biggies like Kohler and Roca. The challenge for the brand, Jindal contends, would be to consistently come up with fresh designs. “It also might have to spend more in marketing to match the financial might of global rivals who are positioned as more aspirational,” he says.

Another big task would be to keep the focus intact on the bath fittings and sanitary ware business. “The extension to lighting using the same brand known for upscale bath offerings is risky,” says Jagdeep Kapoor, managing director at Samsika Marketing Consultants. While conceding that Jaquar did a laudable job by using the aspiration upscale strategy to woo Indians at a time when they were becoming world class consumers, diluting the mother brand might confuse people. “Another brand name or a robust sub-brand strategy could have reduced the risk,” says Kapoor. Their greatest task, he adds, would be to fend off challenges from others by constantly upgrading the brand tangibly and intangibly, without losing focus on its core constituency.

The Mehras, however, believe in the premise of their business model and strategy. For them, a shift to lighting is a natural progression. “We are the only company in the world that handles the two portfolios together—bathroom fittings and lighting solutions,” says Rajesh.

When you ask him if Jaquar has set a realistic target of achieving a $1 billion turnover (around ₹6,800 crore) by 2022, Rajesh doesn’t duck the question. “Absolutely. The ball would be out of the park,” he chuckles.

“We always agree to disagree,” says Parichay, son of Krishan, alluding to the chemistry between generations. “But discussions always result in improvement. The second generation encourages us to be bold and ambitious.”

The Mehras, reckon analysts, have done a commendable job in scaling up the business. “Building a ₹3,000-crore family business with zero debt is not an easy task,” avers Saurabh Jindal, analyst at Bonanza Portfolio.

Though Jaquar is a foreign-sounding name and is largely perceived as an overseas brand, it’s rare to have a homegrown company survive the might of the biggies like Kohler and Roca. The challenge for the brand, Jindal contends, would be to consistently come up with fresh designs. “It also might have to spend more in marketing to match the financial might of global rivals who are positioned as more aspirational,” he says.

Another big task would be to keep the focus intact on the bath fittings and sanitary ware business. “The extension to lighting using the same brand known for upscale bath offerings is risky,” says Jagdeep Kapoor, managing director at Samsika Marketing Consultants. While conceding that Jaquar did a laudable job by using the aspiration upscale strategy to woo Indians at a time when they were becoming world class consumers, diluting the mother brand might confuse people. “Another brand name or a robust sub-brand strategy could have reduced the risk,” says Kapoor. Their greatest task, he adds, would be to fend off challenges from others by constantly upgrading the brand tangibly and intangibly, without losing focus on its core constituency.

The Mehras, however, believe in the premise of their business model and strategy. For them, a shift to lighting is a natural progression. “We are the only company in the world that handles the two portfolios together—bathroom fittings and lighting solutions,” says Rajesh.

When you ask him if Jaquar has set a realistic target of achieving a $1 billion turnover (around ₹6,800 crore) by 2022, Rajesh doesn’t duck the question. “Absolutely. The ball would be out of the park,” he chuckles.

X