State Bank of India: Performing asset

SBI Chairman Rajnish Kumar is provisioning for bad loans and forecasting increased profitability for the bank, but has risk of default been exorcised?

SBI Chairman Rajnish Kumar believes that there will be no impact of past credit costs on SBI’s future earnings

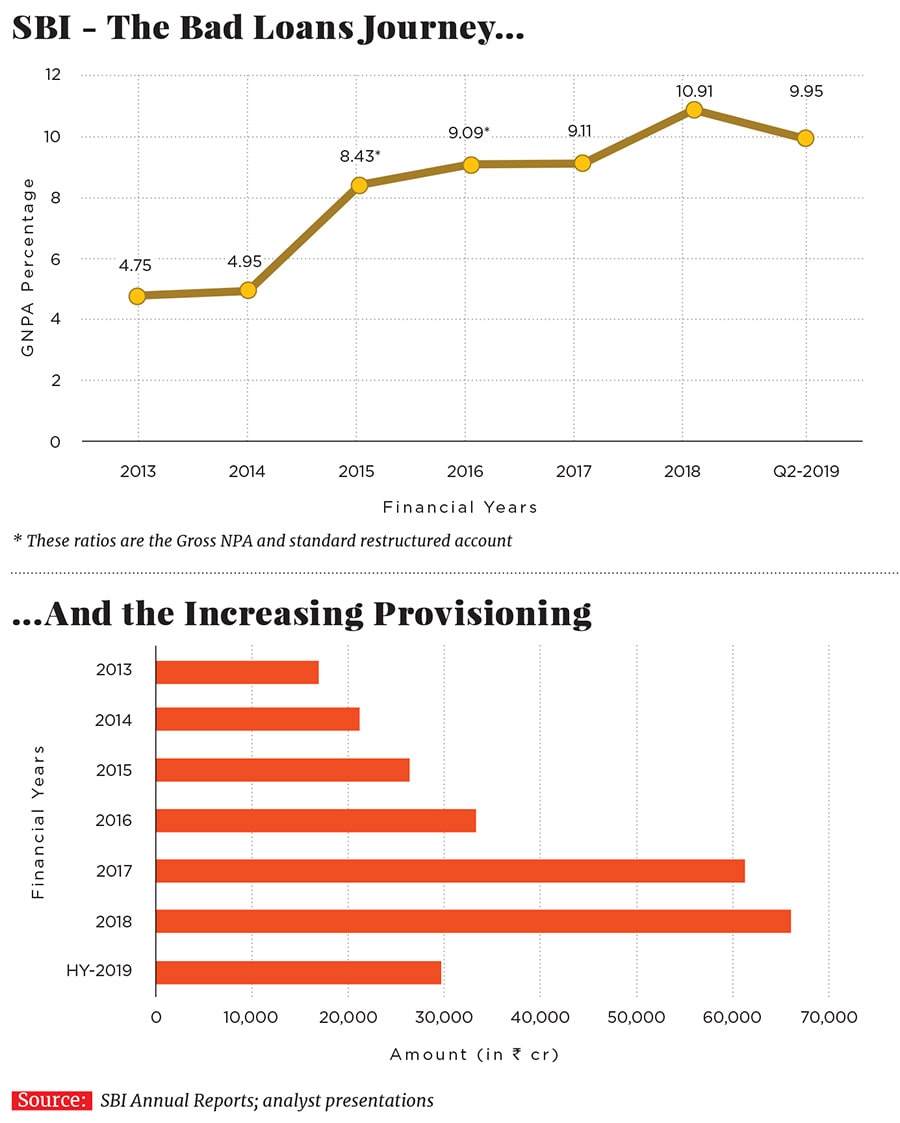

SBI Chairman Rajnish Kumar believes that there will be no impact of past credit costs on SBI’s future earningsWhen Bhattacharya quit, the gross non-performing assets (NPAs) ratio—bad loans as a percentage of total loans—rose to 10.91 percent in March 2018 from 4.95 percent in FY14. The mega six-way merger of five of SBI’s associates—State Bank of Patiala, State Bank of Bikaner and Jaipur, State Bank Of Hyderabad, State Bank of Mysore, State Bank of Travancore and Bharatiya Mahila Bank with SBI in 2017—which was touted to boost the bank’s profitability, hurt its earnings. In fact, it ended up ballooning losses and NPAs for the parent bank during 2017.

There could not have been a more challenging time for Kumar, an SBI veteran of over 38 years. He chose to handle the situation in his own calm way. Two days after taking over, he sent an email to all employees, addressing “a severe trust deficit” in India’s financial system and the need for SBI staffers to “promote moral and ethical grandeur unconditionally” in their daily decisions. He also urged them to educate and functionally update themselves in a fast-evolving, technology-led world.

Fifteen months into his three-year-term, Kumar has been able to arrest quarterly losses (and move the bank into a net profit), lower the gross NPA ratio, ensure sustained growth in the loan book and accelerate the bank’s digital presence through the launch of SBI Yono (You Only Need One), an integrated application across all banking functions. Considering improved credit growth and the need for more capital in the future, the SBI board in November 2018 approved plans to raise equity up to ₹20,000 crore through various modes.

“There has been a clear progress on NPAs and stressed assets; it has been the singular development over the past 15 months. The upfronting of provisioning and recognition of NPAs were critical for us. The approach has helped…we have removed the fear of worrying about the impact on the P&L account,” Kumar tells Forbes India.

For any bank, provisioning is an amount which it estimates as a potential loss due to non-payment of dues and is shown as an expense; hence higher provisioning for bad loans hurts a bank’s profitability directly.

Kumar insists that SBI, which reported a net profit of ₹945 crore in Q2FY19, will see an improved performance quarter after quarter in terms of profitability.

Most banks, including SBI, have seen an improvement in their gross NPA from Q1FY19 to Q2FY19, due to reducing ‘numerator’ (amount of slippages and bad loans) and rising ‘denominator’ (credit growth in advances).

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), under the leadership of then governor Urjit Patel—who quit abruptly in December without completing his three-year term—had in February 2018 tightened the norms for resolution of NPAs. As per rules, a loan becomes an NPA if interest or the principal is unpaid for a period of up to 90 days. Banks have also been told to kick-start the resolution process even if there was a default of a day in accounts of ₹2,000 crore and above. The process is expected to be completed within 180 days of the default.

Kumar calls these norms, along with the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code as game changers. He insists that “this discipline” was required, although it may appear harsh.

There was a time when several departments of SBI were tackling the NPA problem simultaneously. “We had a stressed asset vertical but our NPAs were all over—being tackled by the corporate account, mid-corporate and stressed assets teams. Hence credit growth suffered,” explains Kumar, who started as a probationary officer with SBI in Uttar Pradesh in 1980 and rose through the ranks to become managing director (compliance and risk) and even headed SBI Capital Markets previously.

From June 1, the bank created a stressed asset resolution group, under the leadership of its deputy managing director Challa Sreenivasulu Setty. All accounts, estimated to be of size ₹139,667 crore, have been transferred to this group.

The RBI has maintained a stronghold on banks to follow these norms, and so, SBI has to deal with NPAs in a time-bound manner. At the last analysts’ meeting on November 5, 2018, Kumar said he saw “no concern that there will be any impact [to SBI] of past credit costs on future earnings”.

Overall, SBI has filed 378 accounts with the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), worth ₹110,000 crore. Over the past year, SBI has raised its provisioning coverage ratio on the corporate book to 58 percent; 64 percent on the NCLT 1 list (which has 12 of the largest stressed asset accounts worth ₹48,000 crore) and 78 percent on NCLT 2 list (29 accounts worth ₹28,000 crore). Overall provisioning for the bank improved by 655 basis points to 53.95 percent in the quarter ended September 2018, against 47.4 percent for the corresponding quarter a year earlier.

The NCLT 1 list includes a provision write-back of ₹6,000 crore in one account and it is aligned for all other accounts. As and when resolution happens, the gross NPAs will go down further; in the NCLT 2 list the provision is 80 percent and Kumar expects a recovery of over 30 percent—over ₹30,000 crore from NCLT cases alone this fiscal year.

Anil Agarwal, head of Asian financial research at Morgan Stanley, expects credit costs for SBI, currently at over 200 basis points of loans to drop to below 100 bps in FY2020. “Loan growth at SBI has been anaemic between FY17 and F1H19, but is now picking up. The bank is entering the period of falling provisioning, stronger loan growth, higher net interest margins and controlled costs,” he says.

Thirty-five of the 41 brokerages now rate the SBI stock a ‘buy’ or ‘outperform’, while another five suggest ‘hold’ while only one has placed a ‘sell’ call, according to analysts’ recommendations tracked by Reuters.

Most private and public sector banks are continuing to see a pick-up in retail banking, at a time when non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) continue to be impaired with problems of their own ranging from liquidity to building a more robust business model.

There is no magic lending formula that SBI is adopting. As lending to private sector projects remains sluggish, its focus has been towards retail lending (personal, home, auto, agriculture and SME sectors) and government-led projects. Retail constitutes 58 percent of the loan book and corporate constitutes the remaining 42 percent. This was about equal during Bhattacharya’s regime.

SBI had a domestic loan book of ₹17.78 lakh crore, as of September 2018, which grew by 11 percent from a year earlier. “I now expect a 12 to 15 percent rise in our total loan book this fiscal year,” Kumar says.

SBI’s managing director PK Gupta, who heads the retail and digital banking operations, says, “Our strongest growth is in the unsecured personal loans space, where we grew by around 20 percent year-on-year in September 2018.” The personal loan book of ₹129,764 crore size grew by 20 percent in September 2018, from a year earlier. The average ticket size for such loans is ₹1-3 lakh.

While the income for the young in India continues to grow, their ability to service larger loans will also increase. However, household indebtedness is on the rise with Indians taking multiple loans for different lifestyle needs. And there is room for more growth. As per the Bank for International Settlements data, India’s household credit (proxy for retail loans) to GDP ratio was 11 percent, compared to 78 percent in the US in 2017.

Housing loans are the second-fastest growing segment for SBI, with a 13 percent year-on-year growth across India. In the case of automobiles, where the sector continues to witness poor sales in passenger cars, loan growth has been muted at around 8 percent as of September 2018. Agriculture and SME lending are the weak links in the loan book, with the former muted at 2.30 percent and the latter at just 5.2 percent year-on-year in the September-ended quarter. In the SME segment, though SBI has a market share of nearly 20 percent, it faces strong competition from NBFCs and microfinance firms.

SBI’s agriculture-linked NPAs are high at 11 percent. Farm loan waivers announced by the state governments of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh are likely to have an impact on the way banks lend to this sector. Recurring loan waivers have a clear impact on credit costs and disrupt repayments by farmers.

“We will have to see how it [loan waiver] impacts us,” says Gupta. In the near term, SBI could see a rise in NPAs in agriculture loans, but these levels will come down when the government decides to release money to the banks.

The MODERN DIGITAL BANK

As the cobwebs of NPAs are shredded, SBI has moved faster than other government-owned banks to build itself into a technology-savvy bank, which is keen to automate and streamline operations.

Its digital transformation can be understood through this statistic: Only 17 percent of SBI’s customer-related transactions take place at an SBI branch; 30 percent are at an ATM and six at a kiosk/business correspondent. The balance, and maximum, 40 to 45 percent are through online and mobile banking. The share of UPI/BHIM transactions in SBI’s total digital transactions is 21.31 percent.

Its singular consumer-facing application is SBI Yono, where pre-approved personal loan can be placed within a minute. Housing and car loans are also immediate and paperless, but for one leg of the process where customers will have to visit an SBI branch or processing centre for verification and signatures. “But this process up to disbursement of a loan will be digitised by April this year,” claims Kumar.

Yono offers a range of activities from online shopping, banking, investments, bill payments, tax saving and bookings through nearly 100 e-retailers ranging from Amazon, Jabong and Myntra to Tata Cliq, Yatra, IRCTC, Oyo, BookMyShow, Ola and Uber. The idea is to take on private banks such as Kotak 811, DBS Bank, ICICI Bank and Axis Bank through one integrated platform.

Yono has 5 million customers and an additional 10 million on SBI, the mobile banking application.

SBI will soon introduce Yono cash, wherein one can make a request to withdraw cash completely cardless. This can be done on the Yono application by keying in the amount and creating a PIN. On reaching the ATM, the customer has to key out the PIN and mobile number to receive cash.

Both Kumar and Gupta agree that as SBI forays further into the digital space, there will not be a need to set up more physical branches. The bank, post the mega merger with associates, has already rationalised the branch network with 22,414 branches as of March 2018. “We will continue to have 22,000 to 22,500 branches across India,” says Gupta.

Digitisation, however, will raise the sensitive issue of hiring. Following the merger, SBI has 258,000 staffers across India. Kumar says the bank will look to hire 8,000 to 10,000 people each year as another 12,000 to 13,000 of its employees retire annually. This means an extremely gradual lowering of staff as it goes more digital. The fear is that the pace of labour attrition should not control digitisation.

NOT WITHOUT CHALLENGES

There is plenty of room to improve at SBI, and analysts have raised some pressing concerns.

“One of the key issues I would be worried about is governance and reportage. Take the IL&FS case. The bank had a nominee director on the preceding IL&FS board, but like several others, did not do the necessary due diligence,” says Hemendra Hazari, an independent banking analyst who publishes his writings on Singapore-based research platform Smartkarma.

Hazari extends this rationale to its current proceedings, indicating concern about whether due diligence relating to these had been done.

Hazari also points out segments that the bank catered to—personal and housing loans—are both not stress free. “Its lending activity is growing at a time when urban unemployment is on the rise,” says Hazari. India’s estimated unemployment rate increased to a 27-month high of 7.38 percent in December 2018 after the total number of people employed in India fell by 1.09 crore, according to the data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE).

While SBI’s lending universe is different, the risk of defaults even in retail banking cannot be ignored, considering Indians are highly leveraged at the moment. Kumar is aware that the bank has to do more to strengthen post-sanction processes in retail lending.

The SBI Chairman says “keeping pace with evolving technology, while managing data and cyber security” will be a constant challenge.

The next 15-18 months for SBI could also see further unlocking of shareholder value through stake sales in SBI General Insurance and SBI Cards.

What Kumar would probably wish for, like Bhattacharya before him, is more time. His rivals at private sector banks such as HDFC Bank, Kotak Mahindra, ICICI Bank and Axis Bank have had long tenures to stamp their vision on the bank.

Nearly halfway into his three-year term, Kumar—seen by insiders as a decisive decision-maker—has ticked off most of the boxes. Some of the huge concerns which the bank faced when he took charge—rising bad loans and the overhang of a mega merger—appear to be behind him. With digitisation gathering pace, Kumar is now thinking like how no other state-owned banker does. “Banks will have to benchmark against SBI and not the other way around,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X