India's optimistic economic recovery yet to reflect in labour market

The Budget must move beyond structural reforms and big infra projects to fund the rural jobs programme, generate urban employment, develop industry-oriented skills, and enable collection of good quality data on migrant and informal workers

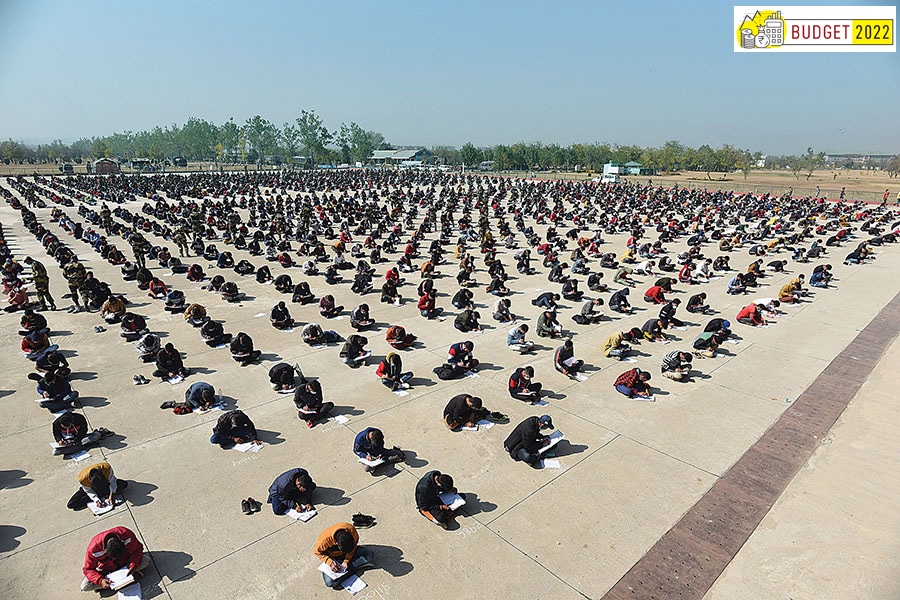

A BSF and CISF recruitment rally in Srinagar. Despite an economic recovery, the unemployment rate touched 7.9 percent in December

A BSF and CISF recruitment rally in Srinagar. Despite an economic recovery, the unemployment rate touched 7.9 percent in December

Image: Waseem Andrabi / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

The optimistic economic recovery in India is yet to reflect in the labour market.

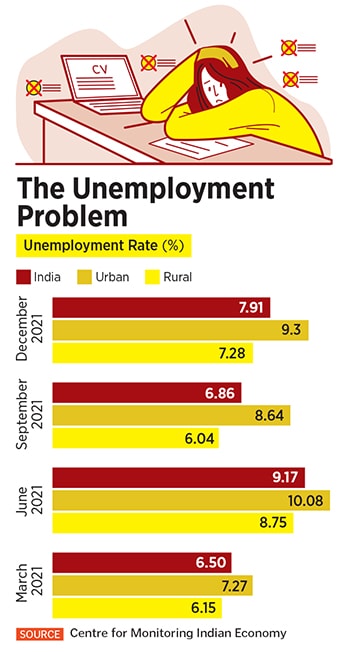

India’s unemployment rate touched a four-month high of 7.9 percent in December 2021, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), which also records urban unemployment at 9.3 percent and rural unemployment at 7.28 percent. Economists tell Forbes India that there continues to be wage and work insecurity among those employed, which makes it important for the upcoming Budget to prioritise creating a targeted, sector-specific approach toward job-creation and skill development.

“Though Budget 2021 helped reduce the intensity of unemployment, it has failed to address the problem in a significant manner. Unemployment is still higher than pre-Covid levels and workers’ participation rate has increased very marginally,” says labour economist KR Shyam Sundar, who is a professor at XLRI, Jamshedpur.

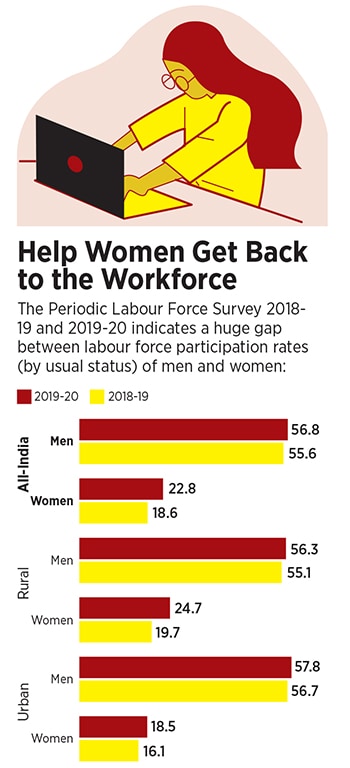

He explains this through the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data released by the government for the January-March 2021 quarter. In urban areas, which saw an exodus of migrant workers moving back to rural areas in the wake of the pandemic, the unemployment rate was at 9.4 percent. This was lower compared to 10.3 percent in October-December 2020 and 13.3 percent in July-September 2020, but slightly higher compared to the pre-pandemic levels of 9.1 percent in January-March 2020.

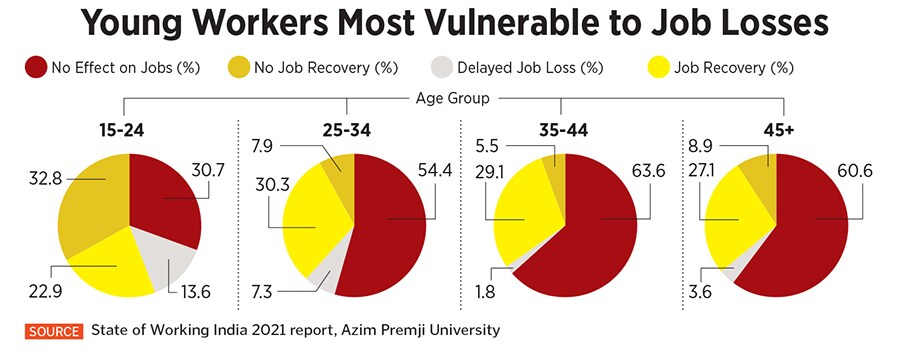

Economists say last year’s Budget, with respect to jobs, was infrastructure-centric and focussed on long-term structural changes. It was supposed to translate into employment, but that has not happened so far, says Rosa Abraham, assistant professor, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University.

Economists say last year’s Budget, with respect to jobs, was infrastructure-centric and focussed on long-term structural changes. It was supposed to translate into employment, but that has not happened so far, says Rosa Abraham, assistant professor, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University. While also focusing on

While also focusing on