Anil Agarwal: India's minesweeper

Bold, strategic acquisitions have shaped the fortune of the Vedanta Resources chairman, who is now focussed on channelling his billions for the greater good

Anil Agarwal, founder and chairman of Vedanta Resources, promised his late grandfather that he would pledge 75 percent of his wealth to philanthropy

Anil Agarwal, founder and chairman of Vedanta Resources, promised his late grandfather that he would pledge 75 percent of his wealth to philanthropy

Image: Mexy Xavier

As he strides across the living room of his residence in South Mumbai, Anil Agarwal looks into the distance where leafy greens give way to sweeping views of the Arabian Sea. “It is often said that what you take from the Ganga, you must return to the Ganga,” says the billionaire boss of Vedanta Resources. Dressed in a sober blue suit and rectangular-framed glasses, Agarwal is a towering figure in India Inc. Not just because he’s almost six feet tall, but also because the self-made industrialist’s London-listed natural resources conglomerate, which turned over $11.5 billion last fiscal, is the sixth biggest in the world (by Ebitda). And with a personal fortune of $3.2 billion he is ranked 44 on the 2017 Forbes India Rich List. (Up from rank 63 and $1.86 billion last year.)

Yet the description of a billionaire disappoints him. “I have pledged most of my wealth. Where are the billions?” he says referring to his promise to give away 75 percent of his fortune to philanthropy—a decision he took with his family in 2014. In fact, even getting this interview with him was difficult. Time constraints aside, Agarwal is disconcerted about being profiled among India’s richest, as this issue of Forbes India sets out to do. “Money is important. It gives you confidence. But I never came from that background, so it makes me uncomfortable,” says Agarwal, whose shaven head and light grey stubble lend him a more rough-and-tumble look.

In his early years growing up in the constricted bylanes of Goria Toli in Patna, Bihar, life was hard, recollects Agarwal. He schooled till the age of 14, barely learning a word of English, and dabbled in his father’s aluminium conductor business. When his ambitions outgrew what Patna could offer, Agarwal, aged 19, journeyed to (then) Bombay to make it as a scrap metal dealer. That was in the mid-1970s. “At that time my only purpose was to make money, to succeed,” confesses the 64-year-old in still patchy English, despite having lived in London for 19 years.

Today, having grown Vedanta Resources into a global giant with operations in aluminium, zinc, lead, silver, power, copper, iron ore and oil and gas crossing four continents and a market capitalisation of around $3.1 billion, Agarwal’s ambitions have changed. The founder, chairman and, with his family, owner of a 69 percent stake in the company, still wants to grow Vedanta and has long talked of turning it into the next BHP or Rio Tinto. But through that growth he wants to give back. By developing India’s natural resources sector, he believes, jobs will be created and poverty eradicated. “India needs many more companies like ours,” he says. In turn, Vedanta’s growth fuels Agarwal’s philanthropic ambitions. He recalls a time about ten years ago when his late grandfather took an oath from him. “He wanted me to pledge 90 percent of my wealth. I negotiated and we settled on 75 percent,” he says, chuckling infectiously.

From the outset when Agarwal worked as a scrap metal trader in Kalbadevi—the heart of Mumbai’s metal market at the time—Rasiklal Shah, an established metal merchant, recalls the young Agarwal’s fiery grit. “He was very clever and always set his sights on the big picture,” the retired 89-year-old says in Gujarati. Back then Agarwal worked out of Rasikbhai’s compact office using a small desk and a shared telephone line. He would collect scrap metal from cable companies and sell it to other traders, including Rasikbhai who became his trusted business partner. When the chance to buy Samsher Sterling, an ailing Mumbai-based cable making company, came up in 1979, Agarwal jumped at it. He didn’t have the money for it, but no opportunity was too outlandish to pursue. He recounts sitting at a local bank for days until the bankers relented and gave him the money he needed. “After he bought the factory, there was no looking back,” says Rasikbhai.

And so it was. Agarwal ran Samsher Sterling for several years, but those were difficult days. “I learnt how to deal with unions, banks, people, customers, machinery, and crises. When you struggle, you learn a lot,” he says. He realised that in order to grow the business, he would have to look at backward integration. Since copper and aluminium were needed to make cables, Agarwal decided to set up a copper smelter—India’s first—in Tamil Nadu. In 1988, he floated his company—what came to be known as Sterlite Industries, named after one of Samsher Sterling’s popular cable brands—and a series of acquisitions followed. In 1995, he acquired Madras Aluminium Company, or Malco, setting foot in the aluminium business, and further expanded his copper business by snapping up mining assets in Australia in 1999. “I wanted to keep growing,” shrugs Agarwal.

At the turn of the millennium when the government was looking to privatise its loss-making mining assets, Agarwal swooped in. He bought a 51 percent stake in Bharat Aluminium Company (Balco) on the cheap in 2001 and orchestrated a turnaround.

So also with Hindustan Zinc. At the time wholly owned by the government, the company was in the red and its zinc-lead mines spread across Rajasthan were believed to have reserves to last for only five years. But Agarwal spotted an opportunity. “He is a man of instinct. He goes by his gut,” says HDFC Chairman Deepak Parekh, who serves as an independent non-executive director on the board of Vedanta Resources.

Agarwal acquired a 65 percent stake from the government in 2002 and infused fresh funds, expertise and technology into the ailing entity. This helped lower costs and boost productivity, making the once uneconomical company essential: Today Hindustan Zinc meets more than 80 percent of India’s demand for zinc. It is the second largest zinc producer in the world after Anglo-Swiss mining giant Glencore and its cost of production is among the lowest in the world. It has reserves to last another 25 years and is also Vedanta’s most profitable unit. “If I find things are in range, I never take time to shoot,” says Agarwal of his acquisition-led strategy.

But it’s not just undervalued assets that he zeroes in on. Vedanta’s purchase of a majority stake in Cairn India, subsidiary of British oil company Cairn Energy, for more than $8 billion in 2011 was an expensive one, says Agarwal. But it was important as it marked Vedanta’s entry into the oil and gas market. Plus, with the merger of the cash-rich energy business into Vedanta Limited (formerly Sesa Sterlite)—the debt-ridden Mumbai listed entity that is 51 percent owned by Vedanta Resources—earlier this year, Agarwal not only streamlined the group’s debt but also came closer to his “dream” of creating an integrated resource major out of India. “BHP is from Australia, Rio Tinto from the United Kingdom, Vale from Brazil. India, too, must have its own natural resources company,” he says.

In fact, some say Agarwal’s purchase of a 12.4 percent stake in Anglo American for $2.4 billion, through his family trust Volcan Investments in March this year, and his upping it to 20 percent for another $1.5 billion in September, is also aimed at furthering that pursuit. Agarwal insists that it’s a personal investment but given the Johannesburg- and London-based miner’s assets, including its ownership of De Beers, the world’s biggest diamond producer, it seems unlikely that he will remain a passive investor. Besides, in the months since Agarwal’s first investment, Anglo American, which was among the hardest hit miners in the commodity price slump of 2015 and 2016, reported healthy results and even beat its debt reduction target.

Back in Agarwal’s seafront villa, he launches into a spirited monologue about India’s potential. The country’s geology, he says, is similar to that of mineral-rich North America, Latin America, Australia and South Africa. Yet we produce only 20 percent of our natural resource requirements.

More than a third of India’s import bill—now at around $500 billion—is spent on petroleum products. This is around 10 percent of the GDP. Oil and gas aside, India also purchases large quantities of gold, silver, coal and fertilisers from abroad. “Instead of extracting and utilising our natural resources, we are spending billions of dollars to import them. We are eroding our national income,” says Agarwal.

His purchase of Cairn India, he points out, was with the view of making India self-reliant. The energy business currently meets 26 percent of India’s crude oil requirement, which Agarwal aims to increase to 50 percent over time. A country that doesn’t produce 50-60 percent of its energy requirements cannot survive, he contends.

In fact, Vedanta meets more than 80 percent of India’s zinc requirements, 95 percent of silver, 50 percent of aluminium and 35 percent of copper, through its various subsidiaries. The group plans to invest $10 billion in the next 3-4 years to grow (and streamline) the existing businesses, as well as launch new ones.

But in its quest to grow, Vedanta has suffered setbacks. An 18-month-long industry-wide mining ban in Goa in 2012 crippled Sesa Goa—Vedanta’s iron ore division which it acquired in 2007. A gigantic, $7 billion aluminium facility in Odisha was held up after local tribals rejected Vedanta’s plans to mine bauxite—the raw material needed to make aluminium—from their lands. The dispute drew criticism from environmentalists and activist investors, but Agarwal appears unruffled. “This is an absolute myth that when mother earth has oil, gold, silver and other resources, you don’t take it out. It’s like taking out milk from a cow—you have to do it sustainably, with heart and soul to make sure you’re not exploiting it. There is a thin wall,” he acknowledges. “And I exactly understand that.” Currently the aluminium facility uses bauxite from other areas and works on 60 percent capacity.

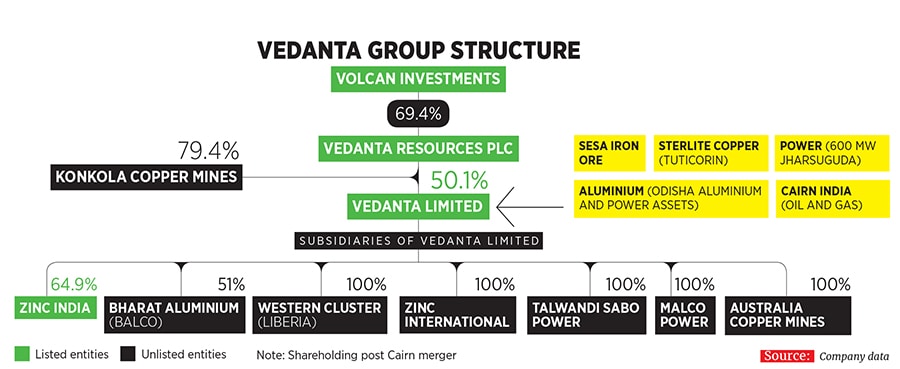

Moreover, complicated as Vedanta’s structure may be—holding company Volcan owns 61 percent of the London-listed Vedanta Resources, which in turn owns 51 percent of the Mumbai-listed Vedanta Limited, which in turn owns various subsidiaries—Agarwal insists that operations are kept simple. Management is left to professionals —son Agnivesh, 34, runs his own scrap metal recovery business in Dubai—while Agarwal helps with strategy and “big picture thinking”, says HDFC’s Parekh. Agarwal for his part ensures that his CEOs have a plan for the future, the ability to develop teams and a knack for working with the government. “We have a world-class team. They are all fully empowered. I’m actually the one who works the least,” he laughs.

But Agarwal’s self-effacing humour hides a shrewd sensibility; that of hiring the right people to get his work done. Take the case of Vedanta’s float on the London Stock Exchange in 2003. No Indian company had done so at that point in time, yet Agarwal, short of growth capital for his expanding business, was clear that London was the place to list. “That is where most metal and mining companies are listed,”

he explains. But he couldn’t do it himself. He needed an internationally known industry veteran to lead the charge, so he hired former BHP boss Brian Gilbertson. The strategy worked. The listing raised $875 million, making it the second largest initial public offering (IPO) of the year. And suddenly Vedanta was among the large mining companies of the world. “The Vedanta IPO showcased India’s potential as a producer of commodities. Before that it was just seen as a consumer,” says Gilbertson, who resigned shortly after in 2004 after equations with Agarwal turned sour. He now chairs London-based mining firm Pallinghurst Resources.

Just as his vision for India, Agarwal’s philanthropic endeavour is hugely ambitious. “Children are our future,” he says. And to that extent he has entered into a public-private partnership with the Indian government’s women and child development ministry to set up 4,000 “nandghars” across rural India. The ₹400 crore investment will entail modernising India’s anganwadis or kindergartens such that children till the age of seven will have access to quality health care, nutrition as well as pre-primary and primary education. Already over 100 nandghars across three states in North India have been piloted. “They have shown a marked improvement in school readiness among children,” says PR Sharma, deputy director, industries and CSR, government of Rajasthan.

These nandghars, says Agarwal, double up as vocational training centres for women. Entrepreneurship training, including credit linkages to start their own micro-enterprises, will be on offer, he says. It’s clear that Agarwal brings forth the same entrepreneurial enthusiasm and foresight to his philanthropy as he does to his business.

“Education is the biggest thing you can give to people,” stresses Agarwal and so his idea of building a world-class university in Puri, on the coast of Odisha, to rival Harvard, Stanford and other great institutions, took shape. “It will not just be a university, but also a powerful research centre, almost like a think tank,” he says. Spanning areas of technology, material and space research, the liberal arts and political science, Agarwal believes Vedanta University—which will be constructed on a 3,800-acre site and will cater to 100,000 students when completed—will help develop future leaders. Initially slated for a 2025 completion, the ₹15,000 crore project has been held back due to a land acquisition imbroglio.

But nothing seems to deter Agarwal. He knows his mind and he knows how to get there. “My grandfather always told me to adjust with people and get adjusted. That’s how you get your work done,” he smiles.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)