Insolvency & debt recovery: Road to resolution

The RBI may offer options to recovery and restructure debt outside the NCLT process

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock As india votes in the general elections, the government continues to list its achievements. Among the most discussed moves of late has been the performance of the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and the utility of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), set up on October 1, 2016.

The NCLT received a major jolt in April when the Supreme Court scrapped a February 12, 2018 Reserve Bank of India (RBI) circular that, through an overarching new framework, directed banks to resolve debts over ₹2,000 crore in 180 days, failing which the debtor would be pushed to NCLT for insolvency. Experts have criticised the circular, saying it did not consider sectoral challenges of companies.

“It was ‘regulatory overreach’. The regulator was exercising the commercial judgement that the banks should exercise,” says Nishant Parikh, partner at Trilegal, a law firm that represents bidders in the insolvency process.

Along with revising the structure for stressed asset restructuring, the RBI also ended all pre-IBC restructuring schemes such as strategic debt restructuring, corporate debt restructuring and sustainable structuring of stressed assets. The Joint Lenders’ Forum has also been done away with.

India does not have a great history in debt recovery, first with Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRT) in the mid-1990s and later with the creation of the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interests (SARFAESI) Act in the early 2000s. After indiscriminate lending, banks, for years, have struggled to recover debt from large borrowers and, thus, has been unable to lend effectively.

According to World Bank estimate in its ‘Ease of Doing Business’ parameters, prior to the introduction of the IBC, India took 4.3 years to resolve a case and the recovery rate for creditors was 26.5 percent; the RBI recovery rate was 13 percent through DRT/SARFAESI. With the IBC, 1,484 cases have been admitted by the NCLT of which 79 have been resolved, with a 48 percent recovery rate. Also, 302 cases have been admitted for liquidation, shows December 2018 data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India.

“Because the recovery rate has increased, significantly less capital has to be invested by the government in public sector banks,” says Nikhil Shah, managing director of Alvarez & Marsal (A&M), a consultancy specialising in business turnarounds. The government had budgeted a figure of ₹65,000 crore as recapitalisation of state-owned banks, to meet regulatory capital norms and capital for growth.

The introduction of the IBC and the RBI circular had political intent. The aim was to ensure that the government would be in a position to announce impressive loan recovery amounts for banks/creditors and the system at large by the 2019 elections. But this has not happened.

Data shows that in several high profile cases, including Essar Steel—where over 600 days have passed since it was admitted to the NCLT—decisions towards resolutions have been punctured by legal challenges (even after the plan was approved by the committee of creditors).

“The IBC has had limited success, considering the delays towards final resolution,” says Sandeep Upadhyay, MD and CEO (investment banking) at Centrum Infrastructure Advisory firm.

The Bankruptcy Code mandates a 270-day deadline to resolve each case, but in several cases the NCLT extended the deadline. Of the first 12 cases referred to the NCLT in May 2017, it approved the resolution plan of only four—Bhushan Steel, Electrosteel Steel, Alok Industries and Monnet Ispat & Energy. Another 26 firms saw mixed progress, with some cases being resolved and others such as the Videocon Group still pending.

The RBI circular took decision-making on stressed assets off the leadership of goverment banks, says Upadhyay. The State Bank of India is an exception: It has seen a 67 percent recovery with resolution of four cases through the NCLT till December 2018.

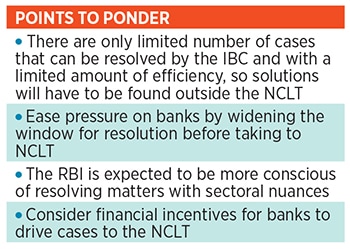

The RBI will consider all alternatives before coming out with a fresh circular. It is expected to consult lenders, bidders, legal experts and government officials before coming out with a revised framework. The window of 180 days before moving a case to the NCLT might be widened.

Shah of A&M says there could be “financial incentives to drive banks to push the companies towards insolvency”. He feels the regulator is unlikely to reinvent the wheel.

The RBI is unlikely to go back to the alternative restructuring options, but is likely to offer resolution options outside the NCLT process.

The banking system also needs a more empowered set of people. “The situation is such that the onus will be on the lenders to decide the merits for the best form of resolution, including insolvency,” says Shah. “There are some businesses and situations that don’t warrant the removal of the promoter. They might just be facing a temporary downturn; some balance sheets can be repaired outside the IBC framework,” says Parikh.

In order to avoid delays in resolution, the NCLT may need to curb admitting and hearing applications and challenges at every stage, which have led to appeals and counter appeals. The onus now is on banks to decide on the best route to recover and restructure debt.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)