Uday Kotak: The institution builder

His bank, now India's fourth largest in the private sector, carries his name. But for intuitive entrepreneur Uday Kotak, it's all about building a lasting legacy of values

Forbes India Leadership Award: Entrepreneur for the year

It was not narcissism which prompted the coming together of the names Kotak and Mahindra. Uday Kotak had decided quite early that he would not refrain from putting his reputation on the line. This resolve became stronger when he read numerous books on top financial institutions like JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley carry their family names. He, too, decided to put his name, front and centre. This thought was reinforced when he visited the United States in 1992, by which time the family name was established.

Today, Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) is the only Indian private sector lender which retains the family names of its promoters. And the institution he has built over three decades has become a byword for credibility and growth in the Indian banking industry.

Vanity had little to do with anything. Instead, it was an abiding belief in his entrepreneurial instincts, one which has been validated many times over. And never more so than in recent times: Little wonder then that the executive vice chairman and managing director of Kotak Mahindra Bank had a distinct spring in his step when he met Forbes India. He greeted us with a broad smile and a bright “good afternoon”, walking briskly, right hand outstretched, leading us into one of the many meeting rooms at the bank’s sprawling headquarters at the Bandra-Kurla Complex, in mid-town Mumbai.

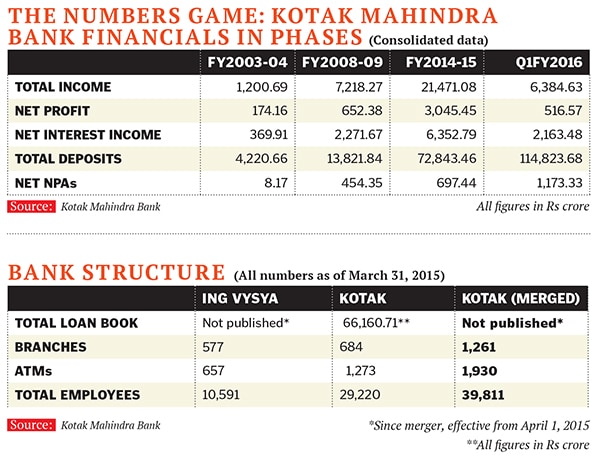

It isn’t difficult to decode the smile. His bank is in the midst of a mega merger, integrating former rival ING Vysya Bank with itself. The $2.4 billion all-stock deal—announced in November 2014 and completed in April this year—has propelled KMB into the big league. It is now India’s fourth largest private sector lender, after ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank, with assets at over Rs 1,66,874 crore and a network of 1,260 branches. The deal has also helped the bank solidify its footprint in South India (where it was weak and ING Vysya always strong) and expand its product portfolio (ING Vysya brings in crop loans, stronger SME business and multinational clients).

The acquisition of Bengaluru-based ING Vysya Bank has a distinct Uday Kotak touch. This was not a hostile takeover or a distress sale: ING Vysya was won over by the comfort level and constant dialogue shared between the banks since 2007. The Dutch financial services group ING —which owned 43 percent in ING Vysya Bank, prior to the deal—had even held a 3.1 percent stake in KMB in 2007. This was later sold through the open market in 2010.

Kotak’s intuitive timing helped elbow out possible suitors, rumoured to include names such as ICICI Bank, IndusInd Bank and L&T Finance. “By 2013-14, things were starting to warm up. We needed ING’s support before talking to ING Vysya Bank,” Kotak tells Forbes India.

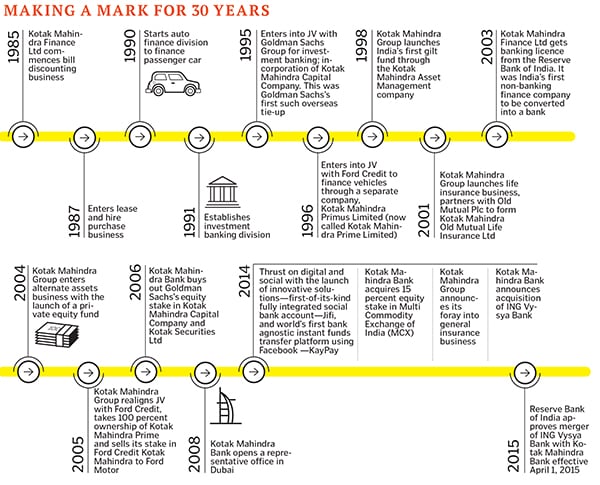

When the merger happened, analysts said the deal maker in Kotak “was alive” and that he was nimble and open to opportunity. It augurs well for a man who for 30 years has constantly adapted to changing environments and opportunities, whether it was his first bill discounting startup; or striking gold with two joint ventures (JVs) with major foreign partners; or surviving the bust of non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and then becoming a bank in 2003, when not many wanted to enter banking.

But the tough end of the trek starts now. Kotak admits that the integration is “challenging”. The financial integration of the balance sheets of both banks has started, as seen through KMB’s June-end earnings. Kotak has spelt out a detailed structure through which key elements from the merger—people, processes, technology and customers—are not compromised with at any stage.

In fact, insiders say Kotak took the first step to welcome ING Vysya into its fold. In the first few weeks prior to the merger, he did multiple town hall meetings and took time out from his calendar to meet at least 200 top ING Vysya people across cities. “That went down very well with the team,” says Uday Sareen, who was CEO-designate at the erstwhile ING Vysya Bank and holds the designation of president, Bank in a Bank, at KMB, evidence of the fact that continuity with change is what the KMB-ING Vysya merger will demonstrate.

The “Bank in a Bank” is a dispensation under which banking operations of the erstwhile ING Vysya will continue to function in their original format until decisions relating to integration of staff, processes and technology are taken. The Integration Management Office (IMO) and “Bank in a Bank” report directly to Kotak and joint managing directors C Jayaram and Dipak Gupta. By April next year, when the entire merger process is expected to be completed, the two departments will be wound up.

“In most mergers or takeovers, one bank takes over the other and puts its people on top. Uday’s clear message to us was: We need to get the best of both in people, processes and technology,” says Mohan Shenoi, head of the IMO—which has representatives from both banks—to oversee the entire merger process. The two banks have already merged treasury and wholesale banking operations.

THE YOUNG ENTREPRENEUR

Born in Mumbai into a large joint family of 60, Uday Kotak had a keen entrepreneurial spirit, inclined more towards finance than his family’s commodities trading business. After an MBA from the Jamnalal Bajaj Institute of Management Studies, Kotak thought of a financial consultancy firm, but a keen eye for opportunity drew him towards discounting bills of large corporates.

He came to know from a friend working at Tata firm Nelco that it borrowed funds for 90 days at 17 percent. Banks lent to companies at 17-18 percent but offered just six percent returns on fixed deposits to individuals, making an 11 percent spread. “I told my family friends that instead of a six percent return, I would give them a 12 percent return,” Kotak says. So he sourced funds at 12 percent and lent onward to reputed companies at 16 percent, making a spread of around four percent. The bill discounting business grew and he formed what was called Kotak Capital Management Finance, which later became Kotak Mahindra Finance Ltd (KMFL).

Like Nelco, Mahindra Ugine Steel was also a Kotak client. It was through this relationship that a game-changing event occurred in 1985, when Uday Kotak first met Anand Mahindra, now chairman and managing director of the Mahindra Group.

Mahindra, just 30 at the time, was impressed with the young Kotak. “When we met, the mini steel business was in recession. I remember asking him why he was willing to lend to us given the industry’s fragility. He promptly replied that his credit evaluation was based on the promoter’s reputation and record,” Anand Mahindra told Forbes India in an emailed response. “I vividly remember being very impressed with his [Kotak’s] maturity and my gut instinct told me this young man was going to make an impact on whatever he chose to do. So rather impetuously I told him that if he ever decided to expand his firm and get into the leasing business—for which the government had recently liberalised licensing—I would be pleased to back him,” adds Mahindra, who lent his family name and invested in KMFL in 1986.

One of Kotak’s closest friends, top corporate lawyer Cyril Shroff, had invested into his bill discounting firm, for similar reasons. “[I] invested in the firm more as friend and well-wisher, and not in a monetary capacity. I would like to believe we always knew Uday was different and would succeed.”

Neither was going to be disappointed.

In 1987, KMFL expanded into leasing and hire purchase, and, by 1990, into auto finance. An initial public offering and further expansion into investment banking and stock broking followed.

During that time, between 1987 and 1994, Kotak—backed by just strong convictions—helped attract and build his core team, many of whom have been with him for over 20 years. This includes Shanti Ekambaram (now president, consumer banking), C Jayaram and Dipak Gupta (both joint MDs), D Kannan (group head, commercial banking), Narayan SA (president, commercial banking), KVS Manian (president, corporate, institutional and investment banking) and Jaimin Bhatt (group chief financial officer).

Ekambaram was among the earliest staffers to join the firm when it was still a leasing and bill discounting company. “In the early days, there were people just shouting about in the office, in trading-type frenzy. I had to roll up my sleeves and become one of them,” she recounts.

TRIAL BY FIRE

The 1990s also brought some highs and lows for Uday Kotak and these helped shape the backbone of the bank. It was, after all, a period of dichotomy for the Indian economy. On the one hand, liberalisation had opened the doors for India Inc. But, on the other, the period from 1992 to 2002 also saw India’s financial markets being rocked by three scams, the collapse of most NBFCs and the Southeast Asian financial crisis.

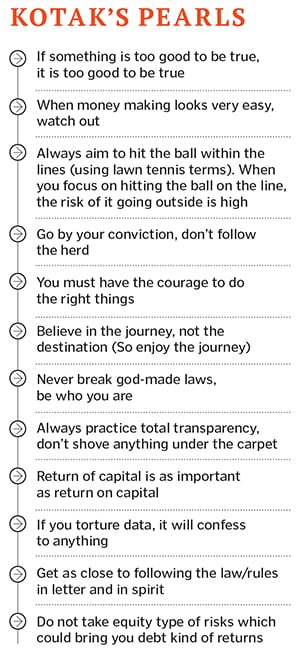

“The [period in the] 1990s was agnipariksha [trial by fire] for us. We learnt the rights and wrongs, staying grounded after making lots of mistakes, as we grew,” Kotak says.

One of the ‘rights’ was looking for learning in the right places. The opening up of the economy prompted a need to understand how global firms operated. “We were in an early stage of capital markets development, more like frogs in a well,” he says. So, in 1995, Kotak struck a JV with Goldman Sachs (their first overseas tie-up) for an investment banking firm Kotak Mahindra Capital Company, in which Kotak Mahindra held 75 percent and Goldman Sachs the balance. And he got much of what he wanted from the arrangement. “Goldman taught us to make presentations, the independence of research and the marketing approach to financial services,” says Jayaram.

A year later, he set up two joint ventures for car finance with Ford Credit International, a Ford Motor company, to finance passenger cars. “The JVs introduced us to processes, governance practices and risk management,” Kotak says.

The JVs with Goldman and Ford ended in 2005 and Kotak is philosophical and realistic about their impact. “JVs are usually between two competitors, they do not last forever. Our process orientation in retail lending comes from [working with] Ford, our equity research [strength] comes from Goldman.”

He is equally candid about the ‘mistakes’ the group made in the 1990s. “When we started taking credit calls in 1995-96 and lent to companies on leasing products, often we would look at the financials and were not convinced about them. But we would assume that other banks which had lent to them would know better than us,” Kotak says. “This created pain for us in 1997-98. Our mistake was that in the early stages of lending, we used to follow the herd.”

Kotak saw the pain and pulled back to shrink the balance sheet in 1998-99, from Rs 1,600 crore to Rs 800 crore. “We saved ourselves because we became paranoid early.”

The 1990s taught them resilience. “We had made several mistakes but were constantly improving, internalising and learning,” says Kotak. “In this phase, we learnt to have our head on our shoulders and were always questioning decisions. We learnt to follow our convictions.” And that mantra has proved to be a fail-safe for them.

ENTER THE BANK

It was this conviction, and Kotak’s drive to become a “meaningful” player in India’s growing financial market space, which pushed Kotak Mahindra to become a bank. KMFL got a banking licence from the Reserve Bank of India in 2003, becoming the first NBFC to be converted into a commercial bank. “At that point, nobody was interested in banking. If we had to be meaningful in India, we had to have a full customer view,” Kotak adds.

But as with all previous milestones, this was a well-thought-out and calibrated decision. “We spent three months debating [about becoming a bank], reviewed projections, and discussed the bank versus NBFC model,” says Manian, who headed the internal project at the time. Kotak sought all the evidence and details: A bank would involve higher costs, defining expansion plans and statutory requirements, while an NBFC would work cheaper with fewer obligations. Manian says the “clinchers” were that a bank would get a wider platform to get and retain customers; it was more scalable than an NBFC and would command better valuations.

Between 2003 and 2007, Kotak Mahindra Bank, as it was now called, continued to concentrate on piecing together technology, processes and branch networks. But going into the 2008 Lehman Brothers crisis, the bank had turned cautious and did not take big bets on the assets side. “Also, it would have been remunerative to get into infrastructure financing, but we stayed away,” says joint MD Gupta. Even in recent years, it has curtailed its exposure to the commercial vehicles and construction equipment sectors.

But as the business environment and outlook improved, KMB stepped up its effort to gain customers, expanded its wholesale banking business and introduced cutting-edge products. In the past 4-5 years, the bank has seen a growth in savings deposits of 40 percent, against an industry average of 14 to 15 percent. This has been boosted by their strategy of providing six percent returns on savings accounts.

CHALLENGES POST MERGER

Today, the bank is riding high on its merger with ING Vysya but not everything about this deal has been sweet. About six percent of the erstwhile ING Vysya book (funded and non-funded) is in various forms of stress, a KMB investor presentation shows. This includes non-performing assets (NPAs), assets sold to asset reconstruction companies, restructured assets and those under a “watchlist”. The integration is beset with challenges. For instance, ING Vysya was not a small bank: It was 65 percent of KMB’s size in terms of branch network. The integration committee of the bank is tackling matters like different provident fund structures, grades and designations for staff as well. Technology, retail assets and core banking operations will be merged in the coming months.

But as is typical with the man, Kotak decided that his bank should take some pain upfront, through the financial merger. In July this year—when the earnings for the combined entity were disclosed—KMB reported a standalone net profit of Rs 189.78 crore, a 56 percent fall from Rs 429.8 crore in the corresponding quarter a year earlier. This was largely due to higher provisioning costs towards retirement benefits of ING Vysya Bank employees, non-performing assets, integration costs and additional interest on savings accounts.

And this is how Kotak has always done things. “One should always practice total transparency; don’t try to shove anything under the carpet. You must have the courage to do the right things. If we believe that this is the way to go, we will not be scared,” says Kotak.

His philosophical approach to business practices is manifested in a chart, the inspiration for which has been drawn from India’s two mythological epics: The Ramayana and Mahabharata. And this has been shared down the line, to enable decision-making that is in line with the overall vision of the bank.

Shenoi explains this concept, drawing four quadrants along the X (letter) and Y (spirit) axes. The first or the ‘Rama’ quadrant is the ideal, when a business decision seems true in letter and spirit; the second, the ‘Krishna’ quadrant, is one where the spirit is met but not so much the letter; the third is the ‘Duryodhana’ where the letter is met but not the spirit; and the fourth is the ‘Ravana’ quadrant, where neither spirit or letter are met. “We sometimes get staff coming to us, saying we are falling in the Ravana quadrant, should we do the contract?” says Shenoi. The answer to that would be an emphatic ‘no’ at KMB.

The bank is also walking the tightrope as it balances its branch expansion with a digital one. Uday Kotak has often spoken about the “rifle shot, not machine gun approach” when deciding on branch networks. But as it goes more kona kona (into every corner)—a thrust which its advertising campaign speaks of—the new world is challenging old mantras.

“We had learnt the 80:20 philosophy, i.e. that 20 percent of the customers make [provide] for 80 percent of the money. But in the new age, 80 percent of customers, which is the long tail, gets you the money,” Kotak says.

The bank is also yet to launch overseas operations, despite having planned for them over the past five years. There are branches of other businesses, but no banking operations outside India. Gupta admits “it is needed” but could take at least a couple of years more.

And a history of growth indicates it would get there.

MAKING BUSINESS WORK

KMB has grown from a team of three people in 1985 to a shade under 40,000 today (including the erstwhile ING Vysya staff). “One of the important aspects about growing a business is to create employment and contribute to society by making it broad-based in what you do, while also benefiting shareholders,” Kotak says.

Here he quotes an oft-reported statistic: If a person had invested Rs 1 lakh into the finance company in 1985, his holding in KMB would be worth Rs 1,100 crore, which works out to an average compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 48 percent over 30 years.

Associations with the right people have played their part too. He fondly remembers his relationship with industrialist and Godrej Group chairman Adi Godrej. Kotak has worked closely with the Godrejs and had helped them acquire Transelektra, which owned the Good Knight brand of mosquito repellents, in 1994. Regarded as one of the savviest investment bankers of this generation, Kotak also recalls with satisfaction the several deals which helped the then Hutchison and now Vodafone to expand their India presence.

The building of Kotak Mahindra Bank with a consolidated balance sheet size of Rs 2 lakh crore is testimony to these two personalities of Uday Kotak: The entrepreneur (in the early years) and the banker. This is where Kotak seems to have gone ahead of some of his seniors.

In the media, Kotak was often associated as being part of the ‘three Ks’ of India’s top dealmakers, the others being Nimesh Kampani, founder and chairman of JM Financial, and Hemendra Kothari, non-executive chairman of DSP BlackRock Investment Managers, who earlier partnered Merrill Lynch. Kothari is almost retired but the firm he built is well set as is Kampani’s JM Financial which is now run by his son Vishal. Kotak, on the other hand, has built a much larger institution, one which is number four in the country’s private sector bank pecking order.

“The issue with businesses is that you have to strike the balance between being an individual and building an institutional platform,” says Kotak. And Kotak’s keen business sense and financial acumen has admirers even in his peer group.

Nearly 30 years on, Kotak still has that eye for detail. Most of his top management team speaks about ‘the homework’ they have to do prior to each meeting. “He knows more than the guy who is making the presentation,” says Sareen, a view echoed by nearly all his senior colleagues. Chances are, when a presentation is being made, Kotak will quickly fish out his calculator (yes, he still uses one, say colleagues) and ask deep, probing questions about that line of business. Arvind Kathpalia, group head of risk at KMB, recounts that when he was interviewed for the bank job in 2003, Kotak asked him the financial costs of setting up an ATM. He also quizzed Kathpalia on how he would choose between “substance and form”.

And if you are sitting quietly at a group meeting, be ready: Kotak will pick your brains, not to test you, but to ensure that everybody is involved in decision making. While he is among the few bank heads active on Twitter, he is more old-world when tracking numbers, a world he is most comfortable in. “He rarely uses Excel sheets, everything is on the calculator,” says Gupta.

Now, having completed one of the biggest deals of his life, Uday Kotak knows rest is still far away. The next three quarters could well go in ensuring that the ING Vysya staff—the newest entrants into the Kotak Mahindra fold—find their space and role. There may be less time to spend with family and none at all for his once-favourite hobbies, playing the sitar and cricket (he was taught the game by Ramakant Achrekar, Sachin Tendulkar’s coach).

But as with the journey the bank has taken to date, some things are certain. There is no frenzied race to the top. KMB will continue to grow in a calibrated manner and will scale up only when there is a chance to create value, as was the case of the mega ING Vysya buyout.

Kotak and his team are clear that they will continue to do what is right by the organisation and its stakeholders. In the process, all their energies will be devoted to delivering what the bank and its founder have worked towards: Making the bank “bigger, bolder and better”. That is the legacy Uday Kotak is building. One measured step at a time.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)