AP Hota: Taking India's digitalisation story forward

Veteran banker AP Hota helped execute a series of reforms in India's payments solutions space. Now, he's using his skills in a project that could transform the world of trade and commerce

Image: Vikas Khot

Image: Vikas Khot

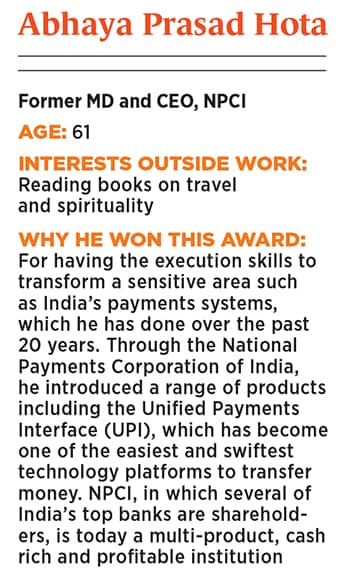

Forbes India Leadership Awards 2017: Best CEO-Public sector

Individuals working in corporates or government-backed institutions rarely effect policy changes whose impacts are felt widely. But that is what the case has been with Abhaya Prasad Hota almost all through his career.

Consider this: Over a 37-year professional span—a bulk of it at the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)—the veteran banker and former MD and CEO of the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) has been consistently involved in strategising and modernising payments methods.

In the past year—particularly post-demonetisation—Hota, and the institution he led until August this year, NPCI, have become household names. And now, retired from government service, the 61-year-old is continuing his digital journey by taking India’s digitalisation story forward. He is currently a consultant with SWIFT India (which allows lenders to exchange transaction-related messages), where he is working towards digitising documents of trade in India. Hota was offered this project by SWIFT India chairman MV Nair, a former banker who headed Union Bank of India. Hota is also going to be part of a team working on a World Bank project that will advise the Bangladesh government and its central bank in identifying areas of improvement in the digital payments space.

Hota has come a long way from the remote western district of Kalahandi in Odisha where he grew up. He initially studied science, but switched to arts, getting a post-graduate degree in literature from Sambalpur University in Odisha. But what he really wanted to do was join the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and become a district magistrate.

He was not selected for the IAS and soon, in 1980, joined the government-owned Steel Authority of India (Sail), where he dealt with contract labour at the company’s steel plant in Durgapur in West Bengal. “I thought of it as a launch pad for a bigger government post,” says Hota to Forbes India.

KEEPING TRACK OF CASH

The goal was in place but he didn’t know how it could be achieved. A few months later when he met a friend who worked at RBI in Kolkata, he thought perhaps that was the route to go and joined the central bank’s office in the city in September 1982. Like all young officers, he was put through the grind. He was first posted in the currency management department, where large stacks of monies are counted and supplied to the currency vaults of banks. “It was tiring to work for more than eight hours a day, in places where ventilation is poor,” Hota recounts.

But the Kolkata posting, where he worked till March 1991, was also a sort of turning point in his career. After four years in the currency management division, Hota, who was seen as a quick learner, was in 1986 transferred as a manager in the technology department. At the time, the RBI was trying to computerise its clearing house operations in Kolkata, something Mumbai had already achieved in 1980.

His computer training involved travelling to Hyderabad and later Australia, he recalls. The computerisation of clearing operations, which sped up the clearing process, was the first step India took towards the modernisation of the payments system and Hota, though just a young officer then, found himself in the thick of things.

At that time, about five centres had already been computerised, but the going was tough in Kolkata due to resistance from labour unions. “Even electronic calculators were not allowed inside the premises,” says Hota, so using computers was out of the question. Trading and clearance work came to a halt for nearly two weeks due to unrest by labour unions, which feared job losses. The matter was resolved by senior regional officers at RBI along with representatives from the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (Citu).

Another revolution was the introduction of the mechanised processing of cheques using magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) technology. The technology, which came about in the late 1980s, brought quicker realisation of cheques and better housekeeping at banks. Hota was quick to catch on. “Kolkata was a late starter, but it came with high quality—the reject rate and error percentage was low, so the clearing house became the benchmark for quality,” he says. This was largely because they had their ear to the ground and learnt from the glitches other centres had faced.

In 1991, Hota was picked by the RBI central office in Mumbai to lead the electronic payment projects there as manager. The most common form of payment at that time was cheques and there was no electronic fund transfer. The RBI was working on how to transform payment methods to chequeless payments.

Over the next few years, Hota rose from the position of manager to assistant general manager and then deputy general manager, being appointed towards the end of his term as a project officer to oversee all electronic payments—electronic clearing system (ECS) and electronic funds transfer (EFT). In 1999, Hota further honed his technological skills by undergoing training in Memphis, USA, on IBM systems, getting ready for his new role.

Image: Dmytro Zinkevych / Shutterstock

INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS

From 1999 to 2002, Hota was put in charge of the RBI’s Mumbai clearing house operations. At that time, cheque and transaction-related information was fed into the central bank’s systems, then copied onto tapes and floppy disks and sent to banks. “We introduced a system whereby banks could establish a dial-up connection with the RBI, log in with a username-password and download the data required,” says Hota. User IDs and passwords were changed every week, which were sent in a sealed envelope to banks.

It was a ground-breaking system for “straight-through processing” that helped improve the speed at which a transaction is processed and proved to be a boon for some of India’s relatively new banks such as Axis Bank, HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank, which were technologically advanced enough to adapt to this. “If I look back, it was a daring solution as this was the first time such a process was being adopted in India,” says Hota.

A senior RBI official, who has known Hota for over two decades, says, “Hota is a visionary, his perseverance is amazing. He conceptualised the changes needed in the ECS system at its time and led teams in several projects even in his early days.”

A routine transfer took Hota to Karnataka but he was back in Mumbai in 2005 as head of a new department called the Department of Payments and Settlement Systems of the RBI, a separate institution to supervise payment systems and also to create a domestic card payments network, which then RBI governor YV Reddy was keen to implement. The Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007, to better monitor the functioning of foreign entities such as MasterCard, Visa Worldwide and cross-border remittance providers Western Union Financial Services, was drafted by the department Hota headed as chief general manager.

When NPCI was formed in 2008, as an umbrella organisation for all retail payments systems in India, Hota was sent there on deputation from RBI in February 2009. NPCI was a not-for-profit company, set up with the guidance and support of the RBI and Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), with 10 core promoter banks—a mix of six state-owned banks, two private banks and two foreign banks operating in India—providing a capital of `10 crore each. “We started from a small office at Stadium House, Churchgate,” says Hota, adding that the first day was spent informing promoter banks to depute officers to NPCI and finalising an agency to create the company website.

By 2013, the institution had implemented the inter-bank ATM transactions clearing and cheque truncated system (whereby the physical movement of the cheque would be eliminated in the clearing process and instead an electronic image of the cheque would be sent along with relevant information to banks).

THE BATTLE FOR THE CARDS

NPCI also set out to introduce new products, one of which was RuPay (a domestic debit and credit card system), an RBI initiative to take on stronger global card issuers such as Visa and MasterCard, which had grown by focusing on urban India. Policymakers were keen to provide a challenge to global players and ensure what Hota calls, a ‘universalisation’ of card payments.

RuPay, which was launched in 2012, now accounts for nearly 43 percent of the cards issued in India, through over 750 issuing banks to 395 million users, according to NPCI data. “Though it is a card being used by the middle- to lower-income segments of people, the truth is it has not been swallowed up by the might of Visa or MasterCard,” says Hota.

Another innovation was the implementation of the Immediate Payment Service (IMPS), which allows for peer-to-peer bank payment transfer. Over 200 banks across India offer the IMPS facility.

UPI, THE GAME CHANGER

Though the IMPS system worked well, it required a revamp. “We needed a new functionality for IMPS. IMPS facilitated sending money, we wanted a system which would improve collection,” says Hota. Enter UPI—built on the existing IMPS system—which the NPCI started working on in 2015. “We thought the IFSC code and other details were still too cumbersome. We wanted to make transacting simple with a Gmail-type address.” UPI, a mobile application, was announced in May 2016 and launched a few months later. With a single click, UPI provides for instant money transfer through a smartphone, 24x7.

“ There is no question of India going back on digitalisation. But there is a lot of scaffolding which needs to be removed

When demonetisation was announced in November last year, UPI got a huge fillip. “If it [demonetisation] had not come, the volumes would not have been so strong. Demonetisation has given an impetus to all digital products,” says Hota, adding, “India already had a strong credit card payments system in place, IMPS was also functional and so was [the unique identification number] Aadhaar. The government had, by late last year, become more confident about launching demonetisation.” Now, over 60 banks across India are UPI-enrolled and in September 2017, the transaction volumes through UPI were at 30.8 million, a 100-fold jump from 0.3 million in November 2016. The value of transactions rose 60 times to ₹5,290 crore in the period.

A 2016 Google and BCG report has forecast that by 2020, the size of the digital payments industry in India will be $500 billion, contributing 15 percent to India’s GDP. Further, by 2020, non-cash contribution in the consumer payments segment will double to 40 percent.

Commenting on the digital drive that India is seeing, Hota says: “There is no question of India going back on digitalisation. But there is a lot of scaffolding which needs to be removed.” By this, he means the infrastructure which is being built and the acceptance of digitalisation, which has to be gained.

Hota, who retired from NPCI in August this year, is also confident about the organisation’s future. When Hota joined NPCI, it was a single-product organisation—the National Financial Switch project (the ATM transformation project) which in 2010 recorded 1.5 million transactions in a day. By the time he left, it had 12 products with a combined 40 million transactions a day, and a staff of 1,050. The company has cash reserves of ₹485 crore and a net surplus (net profit) of ₹105 crore, as of FY17 and is now working on other big reforms: The tap-and-go payment to facilitate micro-payments digitally through a contactless card platform and another to make bills, tolls and transit payments digital.

State Bank of India’s deputy managing director (corporate strategy and new business) Manju Agarwal endorses Hota’s achievements. “He transformed NPCI into a multi-product organisation. Hota has been willing to get his hands dirty, getting down on the ground to understand what drives technology and has also not been worried about taking on the big names in the technology space,” she says.

REINVENTING HIMSELF

Retirement, however, does not mean sitting back for Hota. He is deeply involved as a consultant for SWIFT India, digitalising trade-related documents. “In trade, all the documents like letter of credit, bank guarantees, bill of lading, shipping, lorry and railway receipts are in physical form. They need to be digitalised,” says Hota.

He however realises the limitations of his role. “There are many things one can do in an executive role that cannot be done as a consultant. SWIFT India will need to implement this project,” he says. He is also a firm believer in India’s need to move towards a less-cash economy, saying, “Cash is injurious to the economy.”

Indeed he has come a full circle: A man who started his banking career ensuring the movement of cash is now working towards its near complete removal from the system.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)