- Home

- Leadership

- Leadership Awards 2024

- How Tata Motors defied the odds to emerge as India's third-largest carmaker

How Tata Motors defied the odds to emerge as India's third-largest carmaker

Tata Motors shifted gears to script a turnaround and is the Forbes India Leadership Awards 2024 Turnaround Star. Now it's gunning for more

Manu Balachandran is a writer for Forbes India, based in Bengaluru. At Forbes India, Manu writes on automobiles, aviation, pharmaceuticals, banking, infrastructure, economy and long profiles among many others. He also moderates many of Forbes India's CEO and CXO events and hosts Capital Ideas, a podcast on the most riveting success stories from the business world. He has previously worked with Quartz, The Economic Times and Business Standard in Mumbai and New Delhi. Manu has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University and a degree in economics from the Loyola College. When not chasing stories, he is most likely obsessing over Formula 1 (Read: Lewis Hamilton), historical events and people, or planning long weekend drives from Bengaluru

Shailesh Chandra, Managing director, Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles Limited and Tata Passenger Electric Mobility Limited

Image: Mexy Xavier

Shailesh Chandra, Managing director, Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles Limited and Tata Passenger Electric Mobility Limited

Image: Mexy Xavier

On February 13, a day before Valentine’s Day, Tata Motors sprung a surprise, a bombshell of sorts.

For the first time ever, an Indian automaker had reduced prices of its electric cars in the country, something akin a strategy followed by Tesla in the US, as battery prices see a significant drop. The price of the company’s wildly popular Nexon had been slashed by ₹1.2 lakh, with another model, the Tiago, receiving a ₹70,000 discount. Tata Motors is India’s largest electric vehicle (EV) maker, cornering nearly 80 percent of the market.

Related stories

“With battery cell prices having softened in the recent past and considering their potential reduction in the foreseeable future, we have chosen to proactively pass on the resulting benefits directly to customers,” said Vivek Srivatsa, chief commercial officer at Tata Passenger Electric Mobility.

Tata Motors’ announcement may have come a few days after Chinese automaker, MG Motors announced a price cut for some of its models, attempting to undercut Tata Motors on its home turf. Globally, Chinese automakers have something of a 30 percent cost advantage when it comes to battery packs that contribute to more than 40 percent of an EV’s cost.

But as though it wasn’t evident, Tata Motors’ decision to counter MG’s move on face value points to one fact: As India’s largest EV maker, Tata Motors now holds a distinct advantage when it comes to dictating prices and, in the process, make it tough for its competitors, as India transitions from a fossil fuel-led automotive industry to alternative fuels.

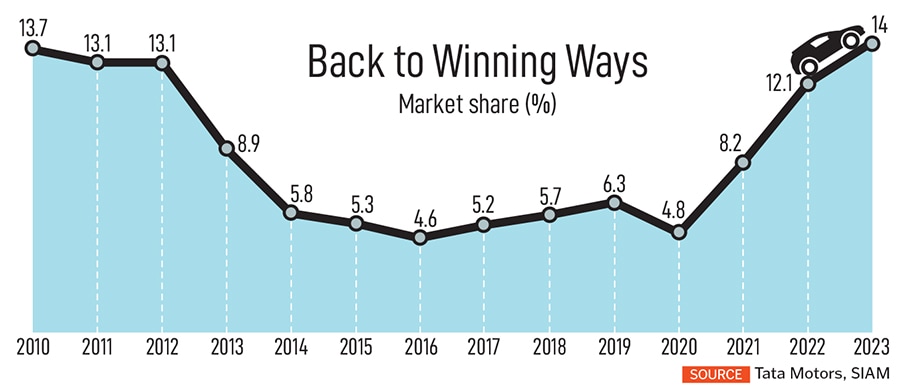

And, in that move also lies the story of Tata Motors, once a pariah of sorts in the Indian automotive world before it emerged as a phoenix, that has scripted a turnaround many can only dream of. Consider this: In 2016, the automaker’s market share in the Indian automotive industry stood at 4.6 percent, down by over 10 percent from 2010. By 2020, that market share had only grown marginally to 4.8 percent, 2018 and 2019 saw some gains, thanks to the launch of some new models such as the Harrier, Tigor, Tiago, and Nexon, before slipping further in customer preferences by 2020.

And, in that move also lies the story of Tata Motors, once a pariah of sorts in the Indian automotive world before it emerged as a phoenix, that has scripted a turnaround many can only dream of. Consider this: In 2016, the automaker’s market share in the Indian automotive industry stood at 4.6 percent, down by over 10 percent from 2010. By 2020, that market share had only grown marginally to 4.8 percent, 2018 and 2019 saw some gains, thanks to the launch of some new models such as the Harrier, Tigor, Tiago, and Nexon, before slipping further in customer preferences by 2020.

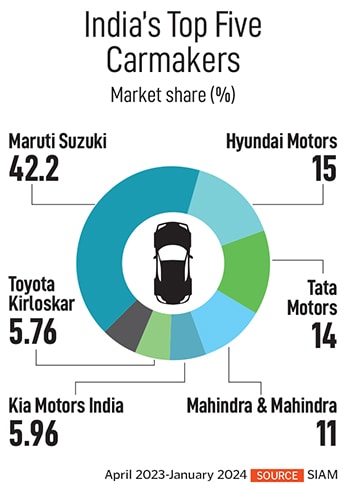

In the four years since then, Tata has grown into India’s third-largest carmaker, with a market share of 14 percent as of January this year, according to data compiled by the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers. Hyundai Motors, India’s second-largest carmaker has a share of 15 percent in a market currently dominated by Maruti Suzuki, with a share of 42.2 percent.

Now, over the next few months, the Mumbai-headquartered automaker is firming up plans to launch two models, specifically to target the 4.3-metre category where models such as Hyundai Creta, Maruti Suzuki Grand Vitara, Honda Elevate, and Volkswagen Taigun, hold sway. Tata will launch its much-awaited Curvv, a coupe, alongside the legendary Tata Sierra, that the automaker says will put it in a sweet spot, and grow its market further, and in the process take the fight to Hyundai Motors.

“If you see the addressable market for us, it is still only 57 percent,” Shailesh Chandra, the managing director of Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles Ltd tells Forbes India. “We are still not participating in many segments which are big in size and growth, like the 4.3 metre, mid-size SUV segment. So our addressable market is still about 56 percent of the full opportunity and in that, we are doing 14 percent. So the real market share in the addressable capacity is nearly 26 percent share.”

The turnaround

In many ways, the real turnaround at Tata Motors dates back to the peak of Covid-19.India’s automobile industry had come to a standstill, and Tata Motors was languishing at the bottom of the personal buyer’s preference. The company’s new models such as the Tiago, launched in 2016, Nexon in 2017, and Harrier and Altroz launched in 2019, were still to drive big sales. In April of that year, Tata Motors also decided to hive off the passenger vehicle business into a separate arm with an eventual plan to seek strategic partnerships there. Chandra, who had successfully led Tata Motors’ EV entry, was appointed president of the passenger vehicle division.

“In April 2020, the brand had fallen on consideration,” Chandra says. “There was a taxi imagery that we had, the market share was 4.5 percent, we would be 6th or 7th in the industry and we had done about 135,000 cars in FY20 which was a run rate of say 11,000 a month.”

To be fair, Tata Motors had already been in the midst of a turnaround, put in place as early as 2016. The automaker had brought in Guenter Butschek as the head of Tata Motors from Airbus, where he had been chief operating officer. Butschek had called that plan the Turnaround 2.0, which saw cost cutting, letting go of numerous platform architectures to focus on just two new models, wider integration with JLR, and making the business more self-funded and profitable.

Still, despite its new models and developments on the product front, there was very little to show in terms of sales even though personal buyers were once again trickling back. “If you see the channel health, only 30 to 35 percent of the dealers were making money,” Chandra says. “Cash burn was heavy in the business because of operational losses. It became very difficult to sustain the investments in product tech. How could you support dealers when you are losing money yourself.”

That’s why Covid-19 in many ways was a blessing in disguise. Overall sales of vehicles had floundered in the country and automakers were careful about splurging their money, in the face of uncertainty. But, the thinking at Bombay House, the Tata Motors’ headquarters, was different, and in June 2020, Tata Motors went all guns blazing. The company splashed the front pages of newspapers with its ‘New Forever’ identity, a move that the company now reckons to be a pivotal moment in its history.

Already, the brand had built up a stellar reputation for its safety—two vehicles were rated four stars while two others were five stars—and its new focus on stylish products meant that the missing brand awareness was slowly being worked upon. The ‘New Forever’ identity led by cars such as Harrier, Nexon, Tiago, and Altroz harped on the company’s high safety standards, better engine performance, driving pleasure, aesthetic design, and rich features, in comparison to some of their previous models.

“That [advertisements] led to a significant jump in inquiry,” Chandra says. “So that gave confidence to our team and we thought that we now have to attack the second problem which is primarily the dealer profitability.” By August, as the economy started limping back to normalcy, Tata Motors increased the prices of its ‘New Forever’ range of vehicles, with the hike ranging between ₹9,000 and ₹15,000.

“We took up the bold call of increasing the price of our cars where nobody was even thinking of doing that because we saw that inquiries were going high,” Chandra says. “We passed on that entire price increase to the dealers, which never happens in the auto industry.” By December of that year, sales were rocketing once again and grew 89 percent in the October-December quarter. Between October and December 2020, the company sold over 68,000 units in comparison to 36,354 units in the year-ago period. It was also the highest number in 8 years. The Tata Tiago and Nexon were the growth drivers, followed by the Harrier, and the Altroz.

“Within 6 months, we had doubled our volumes to around 22,000 units,” Chandra says. “But then we hit a roadblock with capacity and more importantly from a petrol point of view, because, before that we were making mostly diesel cars. Demand was shifting to petrol.” Further investments followed into capacity addition, especially into petrol engines which meant by the end of FY21, total capacity grew to 25,000 units a month followed by 40,000 units in FY22 and 52,000 units in FY23.

“Our portfolio was always strategised with a focus on segments which five years from now are going to be high-growth segments and big in size,” Chandra says. “That went well for us on the SUV side. In FY20, SUV’s share was only 26 percent of the market which went up to 50 percent. Today 70 percent of our volumes are coming from SUVs.” In the process, Tata Motors now says that its dealer network has all returned to profitability with the company seeing its network grow from 800 outlets in 2020 to nearly 1,500 now.

“Our portfolio was always strategised with a focus on segments which five years from now are going to be high-growth segments and big in size,” Chandra says. “That went well for us on the SUV side. In FY20, SUV’s share was only 26 percent of the market which went up to 50 percent. Today 70 percent of our volumes are coming from SUVs.” In the process, Tata Motors now says that its dealer network has all returned to profitability with the company seeing its network grow from 800 outlets in 2020 to nearly 1,500 now.

“Both product improvement and sales/service strategy have been integral to Tata Motors’ turnaround,” Harshvardhan Sharma, the head of auto retail practice at Nomura Research Institute says. “While offering better products has helped attract customers, an effective sales and service strategy has ensured customer satisfaction and retention, ultimately driving sales growth and market share expansion.”

Also read: Parth Jindal and the making of an institution of the future

The game changers

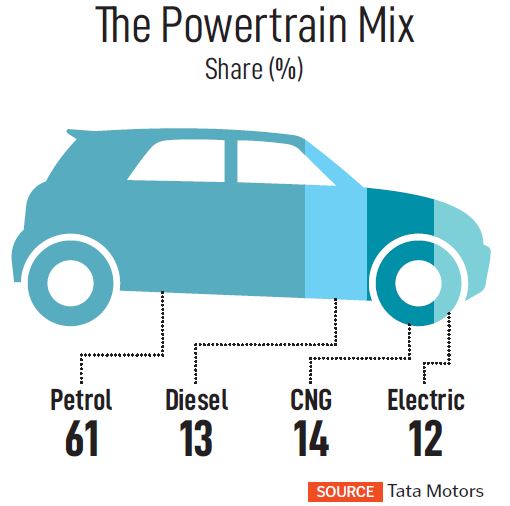

Still, Chandra says his trump card, in all of the turnaround, has also been the pivot to sell multi-power trains. Tata Motors sells diesel, petrol, CNG, and EVs in the country, unlike others such as Maruti Suzuki, which sells petrol or hybrid engines, and Skoda Volkswagen which sells only petrol engines.Even within that, it’s the adoption of electric and CNG that’s giving the automaker an edge over some of its rivals. This fiscal, the company has already overtaken Hyundai in CNG sales, while it remains the market leader in EV sales. “Nobody took the plunge in electric and we now sell about 75,000 vehicles there,” Chandra says. “We were not present in CNG earlier. But now, our run rate is nearly 9,000-10,000 per month. So nearly, 200,000 vehicles have been added because of these two powertrains,” Chandra says. The company had also taken a conscious decision not to leave the diesel segment, with even the new Curvv getting a diesel powertrain.

Today 61 percent of Tata Motors vehicle sales come from petrol powertrains while another 13 percent comes from diesel powertrains. CNG contributes another 14 percent with electric adding the remaining 12 percent. In 2022, that number stood at 72 percent for petrol, 20 percent for diesel, 5 percent for electric, and 3 percent for CNG.

Today 61 percent of Tata Motors vehicle sales come from petrol powertrains while another 13 percent comes from diesel powertrains. CNG contributes another 14 percent with electric adding the remaining 12 percent. In 2022, that number stood at 72 percent for petrol, 20 percent for diesel, 5 percent for electric, and 3 percent for CNG.

Punch and Nexon, which were once envisaged as bridge products while the company identified new models, continue to be the key driver of sales. When introduced in 2017, the Nexon became the country’s first made-in-India, sold-in-India model to register a five-star rating from Global NCAP. Since then, the vehicle, offered in as many as 69 variants, has sold over 600,000 units, helped largely by a robust supply chain. Punch was launched in November 2021 with the company launching an electric version in January 2024.

Since its launch, the Tata Punch was selling roughly 10,000 numbers, before the company decided to launch a CNG variant in August last year. That led to a phenomenal spurt in volumes to 15,000 units a month with the newly launched electric now adding another 3,000 units a month, making Punch India’s highest-selling SUV according to Chandra.

“Earlier, there was a disconnect between Tata Motors and the market and confusion within segments,” says Puneet Gupta, director for the Indian automotive market at S&P Global Mobility. “But they have been ramping up on their partnership with global suppliers, taken a tough call to discontinue some products, introduced some fantastic technologies such as CNG, and is using the might of the entire Tata Group to stage a fantastic turnaround.”

Meanwhile, a critical aspect of the turnaround was also the global semiconductor shortage that put automakers in a quagmire. Tata Motors, Chandra says, had anticipated a global shortage and went on to tie up with additional suppliers, in addition to making tweaks to reduce the use of the chips. “We managed the semiconductor crisis the best and at that stage, the adversity turned into an opportunity with our market share jumping in that period,” Chandra says. “It sustained after that”

All this has meant the automaker has been able to win back customers, and today a significant chunk of its buyers are less than 35 years of age. “If you ask what is different in Tata cars today, they are stylish, safe and is loaded with technology and performance,” Chandra says.

Last year, in a video that went viral, a Tata Harrier was seen crushed by boulders during a landslide, only for its passengers to emerge unhurt.

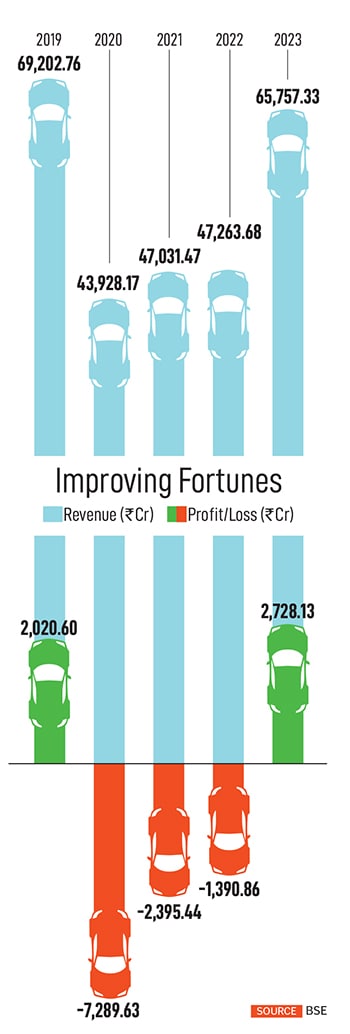

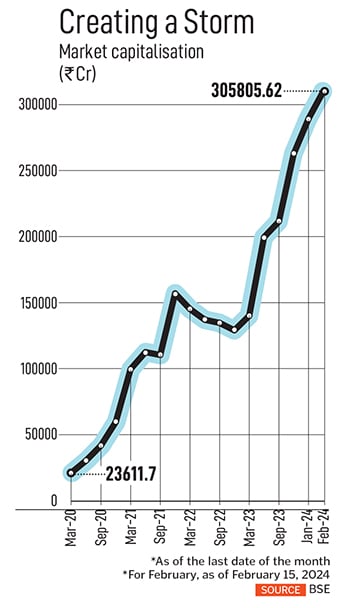

The turnaround in sales has now meant that Tata Motors finds itself on a firm footing financially. Revenues have grown 50 percent in four years, with the company returning to the black in 2023, after being in the red since 2020. Along the way, its market capitalisation has jumped a staggering 1,300 percent to ₹3.05 lakh crore in the last four years.

“If you now see the shape of the profit and loss statement, in FY20, our Ebitda margin was double-digit negative,” Chandra says. “At the end of FY23, we swung it by ₹4,000 crore and Ebitda margin is about 9.5 percent for passenger vehicles and we are negative on the EV. But overall we are still about 6.67 percent,” Chandra says. “Volumes have grown in these three years by four times while revenue has grown five times.”

The next generation

Now, with a portfolio that will target 80 percent of the Indian passenger vehicle market, and multiple power trains to pick from, Tata Motors is gearing up for the next phase of growth, which will see plans to further dominate the EV segment. That’s also a category that will see increased competition with the likes of Tesla, VinFast, and Hyundai ramping up offerings and investments in the country.“Tata Motors’ current strategies and early mover advantage position them well to maintain their leadership in the Indian EV space,” says Sharma of Nomura. “The company has demonstrated its ability to adapt, innovate, and execute strategic initiatives effectively. With continued focus on product excellence, brand building, market expansion, and customer-centricity, Tata Motors can certainly aspire to grow its market share further and compete for higher positions in the industry. However, it will require sustained efforts, investment, and execution excellence to realize this goal.”

Currently, of the 24 million vehicles sold in the country, over 1.53 million are EVs, a phenomenal growth considering that just about 130,000 were sold five years ago. In the four-wheeler segment, from a market penetration of 0.05 percent in 2018, selling a little over 1,500 vehicles, the penetration has risen to 2.13 percent, totalling sales of over 80,000 four-wheelers a year.

Currently, of the 24 million vehicles sold in the country, over 1.53 million are EVs, a phenomenal growth considering that just about 130,000 were sold five years ago. In the four-wheeler segment, from a market penetration of 0.05 percent in 2018, selling a little over 1,500 vehicles, the penetration has risen to 2.13 percent, totalling sales of over 80,000 four-wheelers a year.

By 2030, about 40 to 45 percent of all two-wheelers and 15 to 20 percent of all four-wheelers (passenger vehicles) sold in India will be electric, according to a report by Bain & Co, while the government wants EV penetration to hit 40 percent for buses, 30 percent for private cars, 70 percent for commercial vehicles, and 80 percent for two-wheelers.

Globally, automakers ranging from GM to BMW and Ford are expected to spend over $500 billion in developing all-electric vehicles from gasoline models over the next several years.

GM had, in 2021, said the company would switch to an all-electric fleet by 2035 while Ford had announced plans to go all-electric in Europe by 2030. But, not all of them can boast an ecosystem as the one put together by the Tata Group.

That ecosystem, known as Tata UniEVerse, is one that will leverage group synergies, from companies such as Tata Power, Tata Chemicals, Tata Autocomp, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), Tata Digital, Tata Elxsi and Tata Motors Finance. The company will also soon launch more EVs as part of its second-generation EV plan that includes the likes of Curvv, Harrier, Altroz, and Sierra, before moving into its third-generation EV, Tata Avinya, in partnership with JLR.

“One of the factors responsible for their growth has been their strong belief in the India story,” says Gupta of S&P. “While many global automakers couldn’t commit to the India story, doing flip-flops with their strategy, the turnaround at Tata Motors is reflective of their firm belief in the Indian consumer.”

So is the turnaround now complete for Tata Motors? “I think one of the big strengths of Tata Motors has been its people who have seen this as an opportunity to succeed and be a winner,” Chandra says.

“The pace at which we are coming with different kinds of products is unlikely of a company that was once losing money. But not only have we done it fast, we have also done it very frugally.”

The last four years was about getting back into the game. The next few will be about getting to the top. And in that, Tata Motors seem well on track.